|

Would things

have been significantly different, had their relationship with Acuff-Rose

Music been somehow salvaged? I would hesitate to offer an opinion — on one

hand, it is true that the Bryants and the Everlys wrote some of the best pop

songs on the market during that short late Fifties / early Sixties interval

when rock’n’roll was in decline, and that the strong influence of that

brilliant stretch on the soon-to-follow British Invasion bands is undeniable;

with the brothers effectively shot down in mid-air (or, if you want to take

the industry’s side in this quarrel, effectively shooting themselves in the

foot), they might have missed a real chance to «graduate» as the duo that led

America’s pop music to some of its greatest artistic heights. On the other

hand, we also have quite a few cases of talented American pop artists from

the same time period who, despite not having experienced the same problems,

were still unable to properly hold their ground against the tidal wave of the

new generation — from Roy Orbison to Del Shannon and the like, they either

faded away or had to remain satisfied with some sort of «secondary» status in

terms of fame and fortune.

In the end, it

was probably more of a deep personal tragedy than a global impact kind of

event: what would you feel if you

were an aspiring songwriter, content, perhaps, to work within the relatively

permissive framework of a specific genre such as «country-tinged pop», but

still interested in expanding the limits of its musical language — and then

found yourself unable to pursue that dream through some absurd legal

decision? In a way, it’s a wonder that The Everly Brothers still remained in

the musical profession at all, let alone continued to make their own records

and still try to find new ways in which to express and develop themselves.

Lots of other people would just screw it all and go into real estate instead,

or start selling fine leather jackets. Not Phil and Don, for whom music meant

everything. Well, music and

amphetamines, to be more accurate — but that’s, like, two sides of the same

coin anyway.

Anyway, nothing

predicted a thunderstorm on the horizon as 1961 swept away 1960 and brought

the brothers yet another success with ‘Ebony Eyes’ and ‘Walk Right Back’, two

equally popular sides of the same single that briefly pushed them back into

the Top 10 after the (relative) letdown of ‘Like Strangers’. Frankly

speaking, John D. Loudermilk’s ‘Ebony Eyes’ is fairly maudlin — a pretty, but

somewhat artificial tear-jerker, one of those unlucky ballads that,

musically, sound like a gentle sentimental under-the-balcony serenade but

spoil it all with Terribly Tragic Lyrics (this time, the protagonist’s love

interest dies in a plane crash), and that’s not even mentioning the corny

spoken-word interlude in the middle. It doesn’t help matters much, either,

that the chords and harmonies in the intro are taken almost directly from the

intro to Elvis’ ‘It’s Now Or Never’ — a song that, whether you like it or

not, was at least a perfectly adequate representative of the «romantic-candlelight-prelude-to-a-night-of-passion»

genre. Here, though, it’s like quenching animal passion with a brutally cold

shower.

‘Walk Right

Back’, on the other hand, is a terrific little pop song that the Everlys took

off the hands of Sonny Curtis, who was at his songwriting peak at the time

(‘I Fought The Law’, ‘More Than I Can Say’, etc.). The simple, shuffling

acoustic riff is one of those atmospheric

nonchalant-walk-in-the-park-on-a-sunny-day creations, yet its embedded minor

chords leave some space for melancholy, which makes the lyrics — once again,

about separation, loneliness, and yearning — feel much more at home with the

melody than they do on ‘Ebony Eyes’. The song’s main hook is when the gentle

country-pop shuffle briefly gives way to a near-military march on the "bring your love to me this minute!"

bit, a subtle and clever mood swing that grabs your attention if it had been

previously lost due to the softness of the song — then, for the ultimate

resolution, cuts off the violence once again and drops back into purring

summer day melancholy. Not a bad match at all, Sonny Curtis with The Everly

Brothers.

Then came the

crash — and, strangest of all, over what? A recording of ‘Temptation’, a

rusty oldie from the golden days of Bing Crosby that, ironically, had

originally been produced (way back in 1933) by Wesley Rose, but whose

publishing rights did not belong to him. It was old-fashioned, a little

cheesy, a bit difficult to properly modernize, yet, for some reason, Phil and

Don liked it so much (allegedly, a vision of Don rearranging Bing Crosby’s

version came to him in a frickin’ dream)

that they sacrificed their relations with their own publishing firm to get it

out on the market. It did go on to top the UK charts, but was far less

successful in the US, and, frankly, it’s not the kind of song over which I’d

personally go to battle with the system. Maybe it was just a pretext, though,

for the brothers to fight their own little war of independence — which, for

the moment, resulted in being cut off from recording any songs by their own

major songwriters, including themselves... and meanwhile, their new record

label was impatiently awaiting loads of material for their next LP.

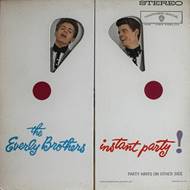

This is an

important angle from which to approach Both

Sides Of An Evening. The fact that no songs on it are credited to either

the Bryants or the Everlys is immediately obvious, but it takes a bit more

effort to realize that no songs on it are credited to any contemporary

songwriters, period — it’s all

folk, country, and Tin Pan Alley oldies from the last three or four decades.

Yet unlike something like Songs Our

Daddy Taught Us, the record somehow manages to avoid feeling like a

nostalgia trip: having lost all their songwriters, the brothers still retain

their loyal Nashville sidemen, and all the songs feature the usual polish,

snappiness, and elegance of America’s finest pop music team at the time. Much

to their credit, if you forget to look up the relevant song information

before turning up the volume, the only vibe you’ll be getting from this stuff

is an early Sixties vibe.

The title of

the record refers to its thematic separation, with livelier and more

danceable songs mostly placed on Side A and slower, moodier ballads occupying

most of Side B — a strategy that seems to have been en vogue around the time (notably, the Elvis team did exactly the

same with Something For Everybody

the same year), but, in my opinion, never manages to stand the test of time:

too many ballads in a row, no matter how pretty or well-polished, are a

serious burden on one’s attention span, and it is hardly surprising that most

of the people commenting on the LP seem to prefer Side A, myself included.

After all, a good landscape is one that frequently alternates between peaks

and valleys, rather than putting the Alps on your left and the Great Plains

on your right. But maybe they thought, at the time, that a structural trick

like this might at least detract some listeners from noticing the overall

«antiquity» of the material.

On which point

they really shouldn’t have worried. The first seven seconds of the album open

with a mighty punch that would soon be directly copied by The Beatles for

their own arrangement of ‘Twist And Shout’, and a racing guitar riff that was

never a part of the original ‘My Mammy’ as sung by, say, Al Jolson in The Jazz Singer. Fortunately for the

Everlys, they don’t have to put on no blackface, but they do have to

rearrange the song so that it now sounds like a contemporary pop number, and

it’s a beautiful synthesis of vocal harmonies, thunderous rhythm section,

complex guitar interplay, and immaculate mix, all of it taking up the space

of just two minutes. Honestly, it could have been a hit, but the brothers

opted for something even more adventurous as the lead single off the album

(and paid the price for it).

That particular

something was ‘Muskrat’, a cover of an old humorous country ditty by Merle

Travis, completely remade as a dark-tinged, almost proto-psychedelic dance

number, with one of the weirdest arrangements in Everly history. Opening with

a «rusty-spring» bass line where each note feels as if bouncing off a rubber

ball, a reverberated swamp-style guitar riff, and a percussion track sounding

like a pack of rattlesnakes, it adds a whole other dimension to Travis’

original set of animalistic metaphors on the «life sure ain’t no rose garden»

idea — the guitars and drums add a nervous, paranoid, and even slightly

shamanistic tweak to the song. For the first time in their lives, it is as if

The Everly Brothers engage in a bit of black magic right before our eyes: I

picture them actually brewing some potent witches’ brew, chanting "muskrat, muskrat, what makes your head so

slick?" and "groundhog,

groundhog, why is your back so brown?" as they calmly disembowel the

poor dumb animals, spilling their guts inside the ugly-smelling black

cauldron or something. Possibly their audiences pictured something similar in

horror, seeing as how the song barely cracked the Top 100 when it was

released in the US (it still reached #20 on the UK charts, though, what with

the Everlys’ overall overseas popularity still at a much higher level than in

their native country — or maybe those Macbeth-reared Englishmen were just

more tolerant of witchcraft).

Anyway, while

‘Muskrat’ is an obvious stand-out track on the album and an odd highlight of

the brothers’ career as a whole, I really dig most of the content of Side A.

The old vaudeville number ‘My Gal Sal’ is remade as a new vaudeville number — slow, sleazy, filled with cool slappy

bass licks from Floyd Lightnin’ Chance and a shrill, piercing, unusually

aggressive electric guitar solo (probably from Hank Garland). ‘Grandfather’s

Clock’ becomes a fast and lively country-pop romp with a Chet Atkins melody

crossing it from top to bottom with the usual combination of speed,

smoothness, and style. Even a hicky throwaway track like ‘Mention My Name In

Sheboygan’ is hard to resist, with Marvin Hughes’ barrelhouse piano dusting

off some long-forgotten Fats Waller vibe and sharpening it up for 1961. And

all through the set, the Everlys’ twin harmonies remain tight, uplifting, and

in no way indicative of any potential troubles clouding the brothers’

attitude. Even if «beneath this mask they are wearing a frown», you couldn’t

really see it.

The «slow side»

is consistently graceful as well but, as I already said, a bit hard to fully

concentrate on. The funny thing is that they actually did two different versions of ‘Hi-Lili,

Hi-Lo’ — a super-slow balladeering take and a fast, upbeat, jazzy take,

driven by a lilting and fluent, Wes Montgomery-style jazz guitar; a few

available versions of the album (such as the digital copy I have, in which

most of the songs are introduced by short spoken introductions by the

brothers) accidentally include the fast rather than slow version, and while I

realize it is a bit banal to always prefer fast over slow, in this case the

exceptional guitar work is a great extra argument (no idea who actually is

playing, though, as the recording sessions for May 31, 1961 show no fewer

than five session guitarists). Yet the concept had to take precedence over

individual song quality, and so the generic version of the record only has

the slow ballad take, alas.

Unfortunately,

the rest of the songs just sound nice;

even if they are all dutifully changed into country-pop clothes, the

potential for transformation is nowhere near as grand here as it is in the

case of ‘My Mammy’ or ‘Muskrat’, and with the exception of the steady bass

clip-clop of the cowboy’s horse on ‘Wayward Wind’, the rest of the ballroom

arrangements get glued to each other and offer few moments of individuality

to anybody but the most persistent listener, which in this case sort of

excludes yours truly. It’s just decent, solidly performed Everly Brothers

balladry, giving you more of those angelic harmonies and first-rate Nashville

arrangements that we already know pretty much everything about.

Of course, you

just might be a sucker for old mushy Tin Pan Alley ballads like ‘Don’t Blame

Me’ re-recorded with a strong, toe-tappy rhythmic foundation and steel

guitars rather than symphonic orchestras — so I’m not exactly saying it’s all

pointless or anything. But if Side A of the album does properly convey an

adventurous spirit — take several different slices of Americana and update

them for the new decade — then Side B comes out as much more perfunctory,

bringing back to mind the simple truth that, one way or another, the Everlys

had to cope with a dearth of new material. For the moment, they did a pretty

good job of masking their troubles; but clearly, this ruse could not go on

indeterminately.

|

![]()