|

And then, right

at the end of 1958, something happened — I have absolutely no idea what it

was, but all of a sudden, it was like Fats got himself a new life on the

black market. The «revival» was heralded with ‘Whole Lotta Loving’, a short,

fast, concentrated explosion of cheerful energy, with perfectly coordinated

boogie-woogie piano rolls and a clever little hook where Fats would replace

the word "kisses" with actual kissing sounds; this did not exactly

break down the Hays Code, but it did call for additional attention, and it

somehow made the artist feel younger and sexier, even if in real life Fats

Domino was probably far from an ideal of the sexiest man alive. In any case,

it became his biggest hit since ‘Valley Of Tears’, about a year and a half

ago, and deservedly so. And, miraculously, it was just the beginning.

Admittedly, the

decision to follow ‘Whole Lotta Loving’ with ‘When The Saints Go Marching In’

(included on the album) was not a very wise choice — I mean, every

respectable New Orleanian artist is probably expected to record the beaten

old chestnut sooner or later, but the song does break up a nearly immaculate

series of singles, and although they take it at a nice break-neck tempo,

there’s practically no piano at all (just a few exultated sax breaks), and

the vocal performance is fairly perfunctory. The B-side (not included on the album) was ‘Telling Lies’, a slower piece of

R&B in the vein of ‘Ain’t That A Shame’, also with fairly little piano

and a pretty unconvincing vocal hook in the chorus (repeating the word

"lies" five times in a row does not immediately turn it into an

earworm — at least, not into a particularly charming one).

Just as it

might have seemed ‘Whole Lotta Loving’ was simply one last gasp of

brilliance, Fats brought it all back with ‘I’m Ready’ (again, not included on

the album) — which is like ‘I’m Walkin’ on an extra steroid, namely, an

expressive piano riff which, in the instrumental section, turns into one of

Fats’ most perfectly constructed boogie-woogie solos (Amos Milburn would be

so, so proud). The best thing about the song, though, is its vocal melody —

there is a peculiarly cool magic to Fats’ phrasing here. The trick is

probably to keep as formally calm

and collected as possible — all

those "I’m ready... and I’m willin’... and I’m able..." sound like

a military person’s stern and decisive replys to being offered a dangerous

mission, except that Fats’ mission is to put you on the road to rock’n’roll

excitement, and by applying military discipline to this faster-than-lightning

performance he really turns ‘I’m Ready’, with relatively little effort, into

one of the finest pop-rock anthems of his generation. You don’t even hear the

song covered too often by other artists because it is unclear how it could

ever be improved upon (the Searchers did a fine, passable version in 1965,

but still added nothing to the excitement level of the original; meanwhile,

The Band really overdid the production for their take on Moondog Matinee).

The commercial and creative successes continued with ‘I’m Gonna Be A

Wheel Someday’, another instantly recognizable Domino-Bartholomew classic,

set to the same frantic rhythmic pace as ‘I’m Ready’ and much more guitar-

and sax-driven than its predecessor, but every bit as inspired when it comes

to the vocal performance. Again, it is the combination of collected,

concentrated decisiveness in Fats’ vocal tone and the speed factor — speed is of the utmost essence here! —

that can drive a listener crazy. "I’M GONNA be a wheel someday, I’M

GONNA be somebody, I’M GONNA be a real gone cat...", a fast triple punch

that knocks you down before you can set up any critical defenses. It’s not that faster than ‘When The Saints’,

but it feels twice as lively and insistent, even without the piano — I do

believe, though, that part of the secret is also concealed in that scratchy

rhythm guitar part that never lets go throughout the song, keeping the energy

level steady high at all times. All of this makes Fats in this era about as

proverbially rock-and-roll as he would ever be, temporarily transcending the

«New Orleans» stamp of quality and, for a brief shining moment, making him the rock’n’roll star of 1959, in that

era when Little Richard, Chuck Berry, and even Elvis would fall behind in the

race, for various reasons.

That said, the slow and sensitive B-side, ‘I Want To Walk You Home’,

sounded as New Orleanian as they come, written and recorded around the

traditional slow R&B shuffle, but remade with a variety of extra touches

— there is that electric guitar again, for one thing, echoing each of Fats’

lines in the chorus, replacing the same old predictable brass backing to make

for a far more intimate performance: it really feels like the guitar is

playing the role of Fats’ little girlfriend here, consenting to his

insistent, but gentlemanly courting. And that combination of a smooth,

delicate attitude with an atmosphere of stalking is what makes the song so

memorable — in live versions of the song, I have sometimes heard him

extending the final "that’s why I want to walk you home, that’s why I

want to walk you home..." to at least twice as many bars as we have here

on the fadeout, playing the perfect smooth criminal to his audience. It’s not

at all creepy, though — just the conduct of a man who knows he has to work

real hard to win his lady’s heart. Quite charismatic, in fact.

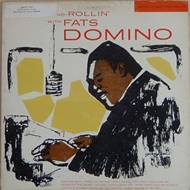

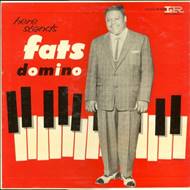

With all this newly found inspiration behind his belt, it is little wonder

that Let’s Play With Fats Domino ends up being Fats’ most consistent

LP since at least Here Stands Fats Domino, or maybe even earlier than

that, because there is one major advantage here — for the first time ever,

the LP does not feel like a mix of creaky, leaky old recordings with a couple

of contemporary singles, but rather feels like a brand new collection of

songs that go together very well. Which is all the more impressive

considering that most of these LP-only tracks are older recordings (dating as far back as 1953!), yet somehow

they fished an impressive number of outstanding outtakes from the bottom of

the barrel, some of which deserve special mention and discussion.

First, the lead-in number ‘You Left Me’, originally recorded in

September 1953, is one of Fats’ best ever ballads — very minimalistic in

terms of vocals and lyrics, precisely so that more emphasis could be made on

Fats’ piano playing. The instrumental part, in which he mixes nervous trills,

barrelhouse rolls, and classical glissandos all over the place, is about as

«virtuoso» a performance as he ever got on tape, and perfectly conveys the

feeling of emotional confusion and chaos, verbally introduced by "you

left me all by myself, and I feel so bad". It’s baffling how this little

masterpiece managed to stay under the table for six long years, and it’s

great to have it here as a reminder of how technically and creatively gifted the man could be at the piano, once a bit

of improvisational spirituality managed to take precedence over pure

catchiness and rock’n’roll excitement.

Another highlight is ‘Stack & Billy’, Fats’ typically New Orleanian

comical take on the classic motif of ‘Stagger Lee’; the angle itself might be

just a novelty bit, but the element that truly distinguishes the song is an

expressive electric guitar flourish, one that you would normally expect to be

included in a solo or confined to a lead-in phrase — but here, it is actually

turned into a looping riff that carries the entire song, adding a degree of

«hyper-activity» to the atmosphere. One might even find it annoying — there

is, after all, a good reason why such things are rarely favored by pop

artists — but I’d prefer the word «amusing», and it certainly makes the song

stand out among a myriad of similarly sounding and indistinguishable tracks

(a similar looping riff also drives ‘Ida Jane’ on the same album, but the

guitar is much more quiet in the mix, making the song command your attention

with much less insistence).

The rest of the filler tracks aren’t all that memorable, but they’re

still fun, like ‘Howdy Podner’ with its exaggerated accent; ‘Hands Across The

Table’ with its cute lyricism ("hands across the table meet so gently /

and they say in their little way / that you belong to me" is just such a

Fats Domino thing to say); or ‘Margie’, the original B-side to ‘I’m Ready’

with a rather extraordinary, convoluted verse structure where Fats even has

to break up his singing rhythm in order to fit in the lyrics. The best news

about these songs is that they do not immediately convey the feeling of

merely being uninspired re-writes of something better — more like timid

tweaks of known formulae that don’t work too well.

Meanwhile, Fats’ winning streak for 1959 continues with ‘Be My Guest’,

released even later in the year; this one takes the old formula of ‘I’m In

Love Again’ and tweaks the beat just enough to get a more poppy than bluesy

feel out of the melody, making it more danceable without losing the Domino

flair. The B-side, ‘I’ve Been Around’, is slowed down, putting the beat back

on the second measure, and made into a rhythmic ballad with the usual

simplistic love message; you may perhaps better know the Animals’ cover of

the song, which they conversely sped up (and ultimately spoiled by replacing

the isolated lead vocal with a silly, quasi-chipmunk choral approach), but

the Animals only do Fats better than Fats when he is not being romantic, and ‘I’ve Been Around’ is about as romantic

as Fats ever gets.

|

![]()