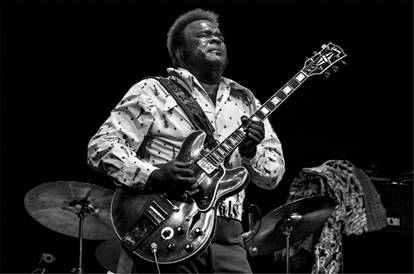

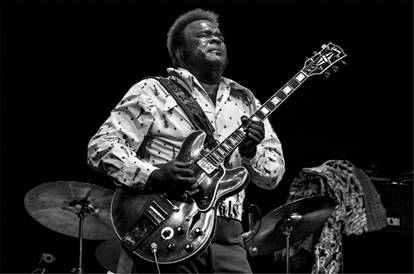

FREDDIE KING

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1957–1976 |

Blues |

I’m Tore Down (1961) |

Page

contents:

FREDDIE KING

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1957–1976 |

Blues |

I’m Tore Down (1961) |

Page

contents:

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Album

released: October 1961 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

2 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) See See Baby; 2) Lonesome Whistle

Blues; 3) Takin’ Care Of Business; 4) Have You Ever

Loved A Woman; 5) You Know That You Love Me (But You Never Tell Me

So); 6) I’m Tore Down; 7) I Love The Woman; 8) Let Me Be (Stay Away From Me);

9) It’s Too Bad That Things Are Going So Tough; 10) You’ve Got To Love Her

With A Feeling; 11) If You Believe (In What You Do); 12) You Mean, Mean Woman

(How Can Your Love Be True). |

||||||||

|

REVIEW Not

only was Freddie King the youngest of the three Kings of the blues world

(Albert King, born 1923; B. B. King, born 1925; Freddie, born 1934, a bare

four months prior to Elvis), but he also squarely missed the chance to become

a «Fifties star» — legend has it that Chess Records refused to sign him

because he apparently sounded too much like B. B. King, and the blues roster

of Chess was sort of like an «anti-B. B. King» thing in that decade. In fact,

Freddie’s only preserved recorded output from the Fifties is a forgotten

single put out on the short-lived El-Bee Records label in 1957 — two songs on

which he does not even play lead guitar (Robert Lockwood Jr., a famous

Chicago session player, is in charge of that job), just sings; neither

‘Country Boy’ nor ‘That’s What You Think’ sound a lot like B. B. King, though

— young Freddy had a far more gritty, rustic vibe to him that actually had

more in common with the big jump-blues performers of the 1940s, like Wynonie

Harris or Big Joe Turner, than with the pompous blues-de-luxe style of the

other King. Ironically,

something similar would happen to Albert King as well, who, despite being the

oldest of the three, struggled to get a career going and did not catch much

of a public eye until signing up with Stax in 1966 and releasing classics

such as ‘Crosscut Saw’ and ‘Born Under A Bad Sign’ — which turned him into a

Sixties’ guitar hero even if he’d been professionally playing blues guitar

since at least the early Fifties. But in the end it turned out to be a good

thing, simply because it was so much more rewarding to become a Sixties’

guitar hero than remain a Fifties’ one. With so many new open possibilities,

such improved studio technologies, and — last but not least — such increased

reverence from white audiences for the ancient art of the blues, the fact

that both Freddie and Albert became «stars» so much later than B. B. did, I

believe, contribute quite heavily to the «cooler» image of both (it would be

difficult to argue that they are more popular than B. B. King, but they are

definitely held in higher esteem by, let’s say, the average «audiences with

discerning taste»). |

||||||||

|

That’s the demarcation line between Albert and

Freddie, on one hand, and B. B. on the other. But there is also another,

perhaps slightly less obvious demarcation line that pits Freddie against

Albert and B. B. — besides age, there is also the fact that both of the

latter came from the state of Mississippi, actually, both were good old

country boys born on cotton plantations. Freddie King, however, was the

product of urban Texas — born and raised in Dallas, then, at the age of 15,

relocated with his family to Chicago, where he had to work in a steel mill

for a while. Naturally, it’s not as simple as just setting up a contrast

between «The Steel Mill Boy» and «The Cotton Field Boys», because both Albert

and B. B. King, as soon as it was possible, «urbanized» themselves to the max

— you don’t really hear either of them playing a whole lot of

pick-a-bale-o’-cotton porch-style acoustic guitar on their records. But the

difference still seeps in in subtle ways, what with Freddie, very likely,

listening to much more R&B and rock’n’roll in his younger days, which

could not help but color his personal style even when he was doing slow

blues, let alone fast boogie. Freddie’s debut single for King Records (no, the

label was not made in his name)

might, upon the first few listens, seem just like another generic slow

electric blues number. There is nothing unusual about the basic melody of

‘Have You Ever Loved A Woman’, or about its main topic, or about its

structure — verse one, verse two, guitar solo, verse three — but when I play

it next to something very very similar by B. B. King, say, ‘Ten Long Years’, it

becomes fairly obvious that there is a serious generational and cultural gap

between the two performers. Unlike the blues performers of old — and quite like the rock and roll

performers of the new — Freddie prefers to get right in your face rather than

keep a respectful distance. The very first vocal line of the song, opening it

before any other instruments come in, addresses you directly, and there’s an

urgency and an intensity in both the artist’s singing and playing that takes

the heat level up a notch compared to Freddie’s natural predecessor on the

Texas blues scene, T-Bone Walker. Interestingly, ‘Have You Ever Loved A Woman’,

melodically no different from the likes of ‘Stormy Monday Blues’ and a

gazillion other 12-bar tunes, is officially credited not to any professional

bluesman, but to Billy Myles, a 1950s R&B and doo-wop artist whose usual

specialty was writing love ballads (like his only own hit ‘The Joker’ from 1957).

In fact, while the very subject of an unresolvable love triangle was no news

for the blues genre, the actual lyrics — "Have you ever loved a woman / So much you tremble in pain? / All the

time you know / She bears another man’s name" — were quite unusual

for traditional blues, whose protagonists were rarely prone to trembling in pain and even more rarely

appealed to their deeply hidden moral compass along the lines of "something deep inside you won’t let you

wreck your best friend’s home". This is a kind of deep-soul blues

that B. B. King himself would only learn to master years later: at the time,

the only bona fide bluesman who specialized in similar material was probably

Otis Rush (‘I Can’t Quit You Baby’ grips you emotionally along the same

lines) — but even Otis’ sound was more introverted than Freddie’s. Small wonder that a decade later, when it turned out

that ‘Have You Ever Loved A Woman’ described the triangular situation between

Eric Clapton, George Harrison, and Pattie Boyd to a tee, Derek & The

Dominos made the song into a major highlight of the Layla album; it’s as if Myles and Freddie specially concocted it

for those super-rare «romantically realistic» situations that almost never

really crop up in true life, at least, not since pure romanticism went out of

fashion in the mid-to-late 19th century. It helps, of course, that Freddie is

every bit as expressive as a singer as he is as a guitar player: although,

unlike B. B. King, he never tried intentionally modeling his image as that of

Soul Brother #1, he had a great natural range and, when circumstances

allowed, he always took it to the max. (Note that in 1960, circumstances did

not yet quite allow to take it to the max — look for various live renditions

of ‘Have You Ever Loved A Woman’ from the early 1970s to truly appreciate

Freddie’s epic potential). While it might be a bit of a stretch to insist that,

with his early singles, Freddie more or less invented the «modern electric

blues guitar» — let alone the fact that, whatever his innovative

contributions might have been, their impact was severely diluted by their

becoming so commonplace in blues music — it’s pretty clear that he was among

the first generation of blues players who truly and verily fell in love with

the sonic sheen of the Singular Electric Blues Lick. It’s easier to

understand if you watch Freddie and B. B. King in live performance, one after

another. B. B. King caresses his «Lucille» like a woman, extracting her

undertones gently and softly; Freddie is the master of the lashing-out style,

tearing at strings as if he were forcefully pinching his loved one’s nipple

in some rough BDSM session — or, if that metaphor’s a little too crude for

you, he’s just sticking knives into his very soul. Again, Otis Rush could do

something like that, but his was a moody, confusing, and wildly unpolished

style: Freddie, on the other hand, understood very well the power of clean,

sharp production, and few people contributed more to the art of appreciating

that sustained high-pitched electric tone as he did. No other American blues

guitar player was more influential on Eric Clapton in his early days with the

Yardbirds, John Mayall, and Cream — and thus, by extension, no American blues

guitar player was more influential on the genesis of the British blues scene,

period. Everybody loved B. B. King, for sure, but everybody wanted to play like Freddie. Interestingly, though, for his first LP his label

decided to slightly downplay the importance of his playing in favor of his

singing — hence not just the title, but also the fact that the LP did not

contain two of his most successful A-sides from 1961, ‘Hide Away’ and

‘San-Ho-Zay’, most likely because they were pure instrumentals (we shall

return to them in the review of Freddie’s second album). This might have been

done out of a vague fear that nobody would buy an electric guitar album just

for the electric guitar (at least unless it was something party-like, like

The Ventures) — but also out of admiration for Freddie’s capacity as a

singer, which was at least as good

as B. B. King’s own, and perhaps even better: there’s something about

Freddie’s delivery that gives it a straight-from-the-heart feeling, while B.

B. King’s approach is a tad more theatrical and a trifle more «calculated

entertainment», with only occasional exceptions. Admittedly, not a lot of those other songs hit as

hard as ‘Have You Ever Loved A Woman’. At this point, Freddie has two

preferred styles — the slow and soulful blues ballad and the mid-tempo

straightforward blues rocker — and typically the songs within each of those

are interchangeable, conjuring up the same moods and relying on largely the

same sets of licks (there are a couple of sharply rising blues phrases that

Freddie likes to insert into almost each and every solo he plays). Of the

blues rocker variety, my unquestionable personal favorite is ‘I’m Tore Down’,

tighter, catchier, tougher, and fiercer than any competition — the best thing

about it is how it synthesizes those feelings of devotion, anger, and

desperation, visible even in Sonny Thompson’s bare lyrics: "I love you baby with all my might / Love

like mine is out of sight / I’ll lie for you if you want me to..." —

then finishing the verse with the defiant logical non-sequitur of "I really don’t believe that your love is

true!", not even bothering to preface it with a "but". Thirty-plus years later,

Clapton would attempt a faithful cover of the original on his From The Cradle album, but while his

own guitar playing on that recording is every bit Freddie’s equal, the vocal

intensity of the original could not be matched. The other blues rockers are a little underwhelming

by comparison. ‘See See Baby’, a King/Thompson mash-up of ‘C. C. Rider’ and

‘Lawdy Mama’, gives a bit too much space to saxophones and pianos and does

not make the best of Freddie’s vocal abilities. ‘Takin’ Care Of Business’,

written by the famous jump blues songwriter Rudy Toombs, sounds antiquated,

as if it came straight out of 1951 or something (that is, until it comes to

the Singular Electric Blues Lick on the solo, sharper and stingier than

anything we could have heard from an Ike Turner around 1951). ‘You Know That

You Love Me’ feels like a pale shadow of ‘I’m Tore Down’, probably written,

as it often happens, on the heels of the former’s commercial success but far

less attention-grabbing. The majority of the songs, though, are slow blues

ballads, a few also sounding rather archaic, especially when they put an echo

on Freddie’s vocals, like on ‘If You Believe (In What You Do)’, which borrows

its primary melodic hook from Jimmy Reed’s ‘Honest I Do’ but fails to live up

to the original’s charming minimalism. Apparently, ‘I Love The Woman’, the

original B-side to ‘Hide Away’, was the song that turned a young Clapton into

Freddie’s lifelong fan, but this might have been by sheer accident if it

simply was the first Freddie King single that Eric laid his hands on: ‘Have

You Ever Loved A Woman’ does all the things that ‘I Love The Woman’ achieves

and more. More famous is the old bawdy blues tune ‘You’ve Got To Love Her

With A Feeling’, earlier associated with the likes of pre-war blues

mischievers like Tampa Red and Brownie McGhee; Freddie gives the song a statelier,

solemn attitude, while still preserving some of the old bawdy lyrics ("she wiggled one time for the judge / and

the judge put the cops in jail"), and the result proved even more

popular with audiences than ‘Have You Ever Loved A Woman’ — apparently, not a

lot of people could (or would) relate to being in love with your best

friend’s wife, but everybody loves them a gal who "shakes all over when she walks". Anyway, it’s really useless to try and make detailed

comments on individual numbers; all that matters here, really, is whether one

gets that «special vibe» from the combination of Freddie’s powerful voice and

red-hot lashing electric style, or not. Clearly, the task was much easier in

1960-61, when you could only compare the style of Freddie King with all the

styles before it, not after; I honestly believe, for

instance, that Clapton would capture both the technical side and the

spiritual essence of all these licks and

take it to the next level as early as on his album with John Mayall and the

Bluesbreakers. Even Freddie himself would continue to grow and mature both as

a player and as a singer, and to the majority of listeners his recordings

from the last five years of his life will probably feel far more awesome than

these, comparatively tame short early singles. But to anybody who does not

run away at the mere mention of «12-bar electric blues» even these tame early

singles may come across as tasteful, enjoyable, and relatable; and that is

not to mention their sheer historical importance, which, in the minds of some

people, often gets automatically translated into genuine entertainment. |

||||||||

![]()

|

|

LET’S HIDE AWAY AND

DANCE AWAY WITH FREDDY KING |

|

||||||

|

Album

released: December 1961 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

2 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) Hide

Away; 2) Butterscotch; 3) Sen-Sa-Shun; 4) Side Tracked; 5) The Stumble;

6) Wash Out; 7) San-Ho-Zay; 8) Just Pickin’;

9) Heads Up; 10) In The Open; 11) Out Front; 12) Swooshy. |

||||||||

|

REVIEW Purely

instrumental blues music, be it acoustic or electric, was hardly big news

back in 1961: almost every singing blues guitarist would have at least a few

instrumental tracks under his belt sooner or later in his career. But the

usual practice had remained, for decades, to stick those tracks away as

«supporting» B-sides or LP-only filler; the regular blues listeners wanted to

buy their records so that they could sing along, or at least get a good

tragic story for their money. Neither Muddy Waters nor B. B. King, as

different as their styles could be, ever dared to put their voices in storage

for their A-sides — as much as B. B. adored his Lucille, she sure needed that

strong masculine presence next to her side in order to emphasize her

«feminine» side. Not that the practice was completely unheard of — virtuoso

guitarists such as Blind Blake or Lonnie Johnson did have instrumental

records in the pre-war period, and Elmore James had ‘Country Boogie’ and a

few others in 1950s’ Chicago — but it was certainly quite rare compared to

the jazz genre, where pure showcases of instrumental prowess were the norm. |

||||||||

|

The most outstanding thing about Freddie King’s

instrumental number ‘Hide Away’, though, is not that it was released as a

single A-side, but that it actually managed to chart, rising as high as #29

in the general charts — an unprecedented success at the time. Granted, the

circumstances were somewhat favorable, and the track, as such, did not

fundamentally emphasize its «bluesiness» as much as it flaunted its

«playfulness». With surf-rock on the rise, and such performers as Duane Eddy

and Link Wray, as well as such bands as The Ventures, already having managed

to draw record buyers’ attention to their fun, catchy, energetic instrumental

hooks, there was no reason why a quintessential blues artist could not go

ahead and try to steal some of that thunder. After all, electric blues was no

longer restricted to the slow and moody 12-bar woke-up-this-morning form, and even an Elmore James could always

follow up a ‘Dust My Broom’ with something like ‘Shake Your Moneymaker’, to

which you could dance your head off just as effectively as to ‘Johnny B.

Goode’. And Freddie King was not the kind of guy who was

going to spend all day slowly and tragically wailing out the emotional licks

to ‘Have You Ever Loved A Woman’. He was a big, burly Texan who liked to kick

ass almost as much, if not more so, than to bare his soul; he might, in fact,

have easily switched to pure rock’n’roll, but he probably had his reasons not

to do it (for instance, he might not have been the biggest fan of the «showy»

vibes of rock’n’roll — and looking over his impressive body type, I do admit

that he might have a bit of trouble doing the duck walk on stage). Instead,

he preferred to inject some of the sharpness, playfulness, and danceability

of rock’n’roll into his blues paradigm — and in the process arguably became

one of the principal creators of that somewhat hard-to-define genre that we

call blues-rock. In fact, ‘Hide Away’ is probably the quintessential

embodiment of early blues-rock as it is. Listening to it today will surely

make most people wonder what the heck was all the fuss about — just a basic

piece of blues-boogie, one out of miriads of possible blues-rock

instrumentals sharing the same core properties. Freddie did not even create

the main theme, borrowing it wholesale from a Hound Dog Taylor composition

(you can hear the same theme on Magic Sam’s ‘Do The Camel Walk’

from the same year); and while it’s a nice theme alright, there is hardly

anything there that makes it more emotionally resonant than any other blues

theme. The one important difference is that this was blues you could dance to

— that Magic Sam recording is, by all means, a walk, while Freddie’s is a merry trot, with the drummer reveling

in his double beats and Freddie laying on a colorful, friendly tone; the guitar

is bluesy in terms of notes, but pop-friendly in terms of the vibe it lays

down, not too different from the atmosphere of The Ventures. ‘Hide Away’ was also unusual in that it was

essentially three different grooves spliced into one: Freddie took elements

from Jimmy McCracklin’s ‘The

Walk’, Bert Weedon’s cover of ‘Guitar Boogie Shuffle’,

and even the ‘Peter Gunn’ theme, and combined them into something that

constantly shifts its shape while retaining the same cocky, taunting

attitude. That way, even if the instrumental’s title was rather prosaically

derived from Mel’s Hide Away Lounge (a blues club in Chicago), it does feel a

little like a tricky game of hide-and-seek. This spirit of playfulness would

completely evaporate from the number in its (arguably even more famous)

version recorded by Eric Clapton with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers five years

later — like everything else he did, Eric took the message much more

seriously than it was ever intended to, and turned it into a fiery anthem of

rock’n’roll defiance. Which sounded awesome, no doubt about it, but had about

as much to do with the original spirit of ‘Hide Away’ as, for instance, all

those Rolling Stones covers of Chuck Berry tunes had to do with their

respective sources. Freddie King does not want to blow you away; he just

wants you to have fun. Nobody at King Records probably expected the song to

take off in March 1961, and, in fact, less than a month later they followed

it up with ‘Lonesome Whistle Blues’, returning to the common vocal blues

practice. However, once the song began to be played everywhere and

established a firm grip on the charts (19 weeks on the Hot R&B list!), it

became apparent that Freddie had unexpectedly struck oil — and from that

moment, his own path in life seemed clear. Already the next single, issued in

July, would be ‘San-Ho-Zay’ (clearly, it’s just a phonetic representation of

‘San José’, but I am not exactly sure as to what specifically the

track has in common with the future Capital of the Silicon Valley), another

instrumental that would be just as successful on the R&B charts, but not

nearly as efficient on the overall ranking, where it slipped down to #47 from

‘Hide Away’s record-setting #29. It’s not difficult to see why that is: ‘San-Ho-Zay’

did not attempt to faithfully recreate the formula of ‘Hide Away’, with all

that playfulness and all those meandering, shape-shifting sections. It is

simpler and more straightforward in nature, riding out a single, focused

blues-rock groove from beginning to end — also, Freddie’s guitar is far more

brutal and aggressive here, playing sharp and nasty sets of licks in ways you

might perhaps expect from rebellious white rockers at the time, like Link

Wray, but typically not from crowd-pleasing African-American performers. From

a purely melodic standpoint, ‘San-Ho-Zay’ was just a generic piece of fast

blues; from a tonal / emotional standpoint, it maybe tried to communicate something that no other black artist

in the electric blues or rock’n’roll idiom would have the guts to communicate

at the time. And when you think about it that way, you become able to assess

those opening bars in a different way — even the rhythm section, with the

bass and the drums delivering the goods in a calm, collected, razor-sharp

manner that carries the same mix of coolness and subtle threat as Booker T

& The MG’s ‘Green Onions’, except it does it one year earlier. ‘San-Ho-Zay’ was followed by ‘Sen-Sa-Shun’, which

was, however, only released as the B-side to ‘I’m Tore Down’, and felt like a

sort of averaging out the vibes of both ‘Hide Away’ and ‘San-Ho-Zay’ — it

rides a mean and lean blues groove like the latter, but tries to make it a little

more vivacious and danceable like the former, plus it also switches back and

forth between two different sections, one dominated by high-pitched electric

lead and the other one delving down into a bass-heavy funky tap-dance. The

source of the tune is fairly clear this time — it takes its voice from Muddy

Waters’ classic rendition of ‘Got My Mojo Working’, and, to some degree, this

is symbolic, given how ‘Mojo’ itself was one of the early precursors to

lively, danceable, and ecstatic blues-rock. It’s a pity Freddie and Muddy

never got to work together — it would have been quite interesting to see them

cross their vibes, even if there’s no guarantee that they wouldn’t simply

«cancel out» each other. By the end of 1961, it must have become clear that

carefully planning a commercially successful career based on instrumental

blues-rock would be a dead end for Freddie — more precisely, that ‘Hide Away’

was a lucky fluke, and once its surprise aspect had worn out, he would not be

able to consciously and deliberately hit even higher heights. Nevertheless,

as long as the iron was hot, Freddie and his band had managed to pump out a

whole load of instrumentals, and, so as not to let it all go to waste, the

label put twelve of the best on an LP that simply had to have both Hide Away (as a blunt reminder to the

public) and Dance (as a magic

charm word) in the title. Not surprisingly, the album did not sell — but

still made history as (probably) the first fully instrumental blues-rock

record in the whole wide world. Discussing all the remaining tracks separately would

be overkill, especially since some of them, like ‘Butterscotch’ or ‘Side

Tracked’, are similarly-sounding 12-bar grooves that will all be lovely if

you love Freddie’s tone and manner of phrasing, but certainly do not inspire

creative writing. ‘The Stumble’ is sometimes singled out as a particular

highlight, mainly due to its having been later adapted by Jeff Beck, Peter

Green, Dave Edmunds, and others; I fail, however, to see how it is any more

outstanding than the rest (a couple of chord changes do indeed differ from

the typical ways in which other blues guitarists would play it, but the same

could probably be spotted on most of the other tracks as well). If there’s any general praise to be offered for the album,

it is how modern it all sounds.

Sure, it’s still 1961, and Freddie is not laying on tons of special effects

or dazzling listeners with speed tricks or hammer-ons, but it is 1961, and you basically already

have all your Eric Claptons, Rory Gallaghers, and Stevie Ray Vaughans (‘Just

Pickin’ = ‘Mary Had A Little Lamb’) in this little package. For those reared

on and accustomed to the sonic standards of the late 1960s / early 1970s —

the days when blues-rock reigned supreme — Let’s Hide Away will, I am afraid, mostly be of historic

importance. But if, for some reason, you find yourself in the mood for just

the core substance without all the extra juice, flash, complexity, and pomp

of what the blues-rock genre would grow into, then early Sixties’ Freddie

King is just the man for you. Fast forward one decade, and Freddie himself would

already play the same things in typically early Seventies’ blues-rock fashion

— unlike some of his contemporaries, he was happy to beef up and aggrandify

his sound to adapt to the spirit of the times, so that loud, sped up and

extended jamming arrangements of ‘Hide Away’ (like this one) would become

the norm for him. Yet some might argue that the «thinner», more economic

sound of the original recordings, with none of that extra fat (and no, I’m not making a subtle reference to

Freddie’s body weight here), makes a more precise point and is actually more

about making a musical impact than showing off one’s swagger. I think there’s

room for both viewpoints in the ballroom of good taste, even if, when it

comes to albums rather than

individual tracks, I’d still certainly go for Freddie’s Seventies’ output —

at this point in history, like almost everybody else, he was still the master

of a two-and-a-half-minute burst of inspiration than of filling up two long

sides of an LP with music that consistently mattered. Ironically, two years after the original release of

the album, King Records re-released it «for the fans», adding fake crowd

noises and retitling it as — don’t laugh, please! — Freddie King Goes Surfin’. Although this is a good candidate for

one of those «Top 100 Dumbest Decisions Made By Record Labels» lists, it does

to some extent agree with my idea here — namely, that ‘Hide Away’ made it so

big not because it was «instrumental blues», but because it was playful and

danceable, which did indeed put it in the same vibe-league with The Ventures

and Dick Dale. One can even imagine how Freddie’s music could anger some

radical blues purists at the time, though, truth be told, «blues purists» had

really gone out of style the day the first bluesmen picked up their electric

guitars — not to mention that even if we’re talking acoustic blues, that

cheerful danceable vibe was at least as old as the ragtime guitars of Blind

Blake and Lonnie Johnson. Besides, apparently Eric Clapton had no problem

with it — and we all know just how much of a «blues purist» young maximalist

Eric was back in 1964-65 (at least, before Jack Bruce, master of all things

avantgarde, taught young Eric how to really

sell out). So, while it takes a bit of an imaginative stretch to picture

Freddie on a surfboard, in a way those King Records were absolutely right.

This is precisely that major point in history where electric blues «goes

surfing». In the end, want it or not, everybody had that ocean across the

U.S.A. |

||||||||

![]()