GENE CHANDLER

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1961–1995 |

Classic R&B |

Groovy Situation (1969) |

Page

contents:

- The

Duke Of Earl (1962)

GENE CHANDLER

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1961–1995 |

Classic R&B |

Groovy Situation (1969) |

Page

contents:

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Album

released: January 1962 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

2 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) Duke Of Earl; 2) Stand By Me;

3) Festival Of Love; 4) Daddy’s Home; 5) I Wake Up Cryin’; 6) Turn On Your

Love Light; 7) Nite Owl; 8) I’ll Follow You; 9) Big Lie; 10) Kissin’ In The

Kitchen; 11) So Many Ways; 12) Lonely Island. |

||||||||

|

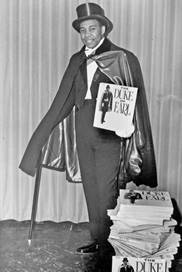

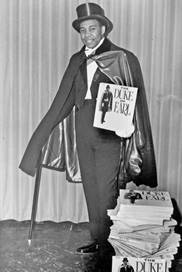

REVIEW Those of us who are still under 80

and have not yet graduated from the

college of pop music history may so rigidly associate «doo-wop» with the

1950s that they’d probably think it officially expired on January 1, 1960,

and was buried the next day to little fanfare, much like the Western genre in

cinema. In actual fact, though, nothing happens that quickly — hey, even rock music occasionally tries to feebly

wave a crutch in the air in 2024 — and both Westerns and doo-wop were still

alive in the first years of the new decade, though already somewhat

struggling to make a critical and commercial difference in the face of

fresher, more attractive distractions. Yet sometimes it still happened: The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance was a

big commercial hit in the movie-going world of 1962, and ‘The Duke Of Earl’

was one of its biggest musical hits. |

||||||||

|

By that time,

Gene Chandler (still under his original name of Eugene Dixon) was already a

recognizable figure in the Chicago area: he had been singing with The Dukays,

one of the city’s many prominent doo-wop ensembles, since 1957 (back when

«pure» doo-wop still competed with R&B for chart dominance), though the

group did not manage to secure a recording contract until 1961, when Nat

Records, a very short-lived label

formed by music executives Carl Davis and Bill Shephard ("Nat" was

apparently the name of their bookkeeper), released their first single, ‘The Girl’s A Devil’,

sounding like a slightly less funny version of the Coasters on this

particular tune. It is not quite clear why they decided to go with a solo

artist moniker — just Gene Chandler, rather than «The Dukays» — with their

next recording that they offered to Vee-Jay Records, but perhaps everybody

thought that by late 1961, vocal groups (at least male ones) were indeed being perceived as something antiquated,

while a «Gene Chandler» could easily be marketable on the level of Sam Cooke,

Jackie Wilson, or Ben E. King. (Another story says it was because of

copyright matters, since Nat Records already owned the legal rights to «The

Dukays», but since «Nat Records» themselves essentially consisted of Gene’s

producers, I am not sure that this could have been a real problem). To be quite

honest, there are few songs in this world that sound as downright silly —

meaner tongues might say stupid —

as ‘Duke Of Earl’. Suffice it to say that if you have ever witnessed Sha Na

Na’s glorifiedly tasteless performance of ‘At The Hop’ in the Woodstock movie, ‘Duke Of Earl’ was

actually the next number in their setlist on that day, and yes, that band

would stake their entire career on glorifying each and every juvenile aspect

of pre-Beatles teen pop music, so no accident here. The song’s title and,

consequently, its entire lyrical setup stemmed from a series of vocal

exercises by The Dukays in which their doo-wop vocalizing eventually

coagulated into «doo-doo-doo-duke of

eh-eh-Earl», which they liked because one of the group members’ name was

Earl Edwards — even if the line would probably have every single member of

the British aristocracy rolling in the aisles, as they might just have well

called it ‘Marquis Of Baron’. "As

I walk through this world / Nothing can stop the Duke of Earl",

sings Gene Chandler in one of the most sugar-drippin’ deliveries of its time

— implying that if something ever

tries to stop the Duke of Earl, it shall immediately encounter a 150%

increase in its blood sugar level and enter a happy, immobilized vegetative

state of existence. It cannot be

said that ‘Duke Of Earl’ is a complete and utter throwback to the mid-Fifties;

the actual vocal progressions are more in line with the contemporary pop style

of bands like The Drifters, and the bridge section in particular strives for

the same soulful tension as one might encounter in some recent Ben E. King

hit. The band’s harmonizing, though, with the trademark separation of high

and low ranges, is decidedly in the old-fashioned doo-wop style, which makes

the song into an interesting musical hybrid. But while I can take some of Ben E. King seriously, ‘Duke Of Earl’ has no

chance to register on any other line than «unintentional comedy». With less

ridiculous lyrics, it would have been a middle-of-the-road pop tune, barely

noticeable against superior competition from Atlantic and Motown; the actual

words, however, give it a defiantly absurdist edge — one that Chandler

himself took care to exploit by buying himself a cape, a top hat, and a

monocle to don onstage, which all but turned him, for a while, into the

second most flamboyant African-American performer in the nation after

Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and his portable coffin. However, the simplest possible

reason for why the song spent 15 weeks on the charts is the magic quality of

its underpinning bass line — the "duke,

duke, duke, duke of Earl" chant that takes the instrumental appeal

of the then-popular descending pattern and translates it to the vocal

language. I can vouch for that — without being charmed by the song as a

whole, I ended up having that pesky pattern in my head for a few days after

sitting through it two or three times in a row. As it often

happens, the main problem with ‘Duke Of Earl’ was that it was essentially a

fluke. None of The Dukays, including

Dixon / Chandler himself, were talented songwriters — they loved doo-wop and

could sing it along with the best of ’em, but that was just about the total

extent of their capacities (and their actual ambitions, I suppose). Apart

from relying on covers of non-original material, their only support from the

contemporary creative world was a lady by the name of Bernice Williams, a

music business manager and part-time songwriter who is said to have actually

discovered Dixon and originally introduced him to his future agent Bill

Sheppard and to the rest of The Dukays. It was she who came in to help

Chandler and Edwards transform ‘Duke Of Earl’ into a finished song, and she

is also credited as the sole writer on four more tracks that constitute

Chandler’s self-titled debut album, although three of them were originally

released on Nat Records and still credited to The Dukays. Of these, ‘Nite

Owl’ is a highly derivative, but mildly fun pop-tinged R&B number that

borrows vocal moves out of everything from Larry Williams’ ‘Bad Boy’ to the

Coasters’ ‘Poison Ivy’ and puts them in the service of a strange hymn to

night prowling (for the sheer sake of pissing off your parents, not in some

depraved Rolling Stones or AC/DC sort of way, mind you); ‘Kissin’ In The

Kitchen’ is a musical variation on ‘Hully Gully’ married to a lyrical

variation on the catch you with another

man that’s the end, little girl theme (not nearly as interesting in

practice as it could be in theory); and ‘Festival Of Love’ and ‘The Big Lie’

are slow and slippery doo-wop ballads, with the former offering another

mighty saccharine overdose while the latter is at least a little bit more

subtle. I suppose this is as good a place as any to mention that Gene

Chandler does have a pretty great singing voice — you know everything he does

is pure vaudeville, but somehow he usually manages to stop precisely at that

line which separates «honest professionalism» from «cringy over-singing». The rest of the

album is mostly padded out with covers, which mainly just remind you of the

kind of market in which Gene and his managers were competing. That said, ‘Stand

By Me’ fares pretty damn well with a tougher arrangement, in which quiet

jazzy electric guitars and thick sax riffs replace the fragile chimes and

strings of Ben E. King’s original — amusingly, that way the song becomes

closer in mood to the famous John Lennon cover from 1975 (I have no reason to

suspect John was a big Gene Chandler fan, though). But ‘Turn On Your Love Light’

adds nothing to the Bobby Bland original, and ‘Lonely Island’ directly pits Chandler

against Sam Cooke, which you can tell is probably a losing battle even

without listening. Nice enough, but utterly superfluous. Returning to the

point made by ‘Stand By Me’, a notable feature of the entire LP is a complete

lack of string arrangements — quite unusual for a sentimental R&B album

in the early Sixties. Something tells me this might simply have to do with

not being able to afford any of the local orchestras, but in any case, the reliance

instead on a combination of piano, saxophone, and electric guitar gives the

songs a bit of a special edge. So even when they decide to cover Burt Bacharach’s

‘I Wake Up Crying’ (previously released by Del Shannon on his debut LP) and intentionally

slow it down so as to try and wring out every ounce of sentimentality and

self-pitying from Chandler’s voice, the backing track remains unusually

classy, with tom-tom percussion, jazz guitar, ragged sax, and occasional

bluesy bursts from the piano merging in a surprisingly refreshing and moody

manner — really, it’s just the kind of sound that would be revived and

amplified by Blood, Sweat & Tears at the end of the decade, and this one

certainly wasn’t as meticulously planned as the BS&T vibe would be. I guess the

main point here is that Gene Chandler should not be judged exclusively by the

novelty value of ‘Duke Of Earl’: he and his Dukays team were serious

performers with a decent sense of taste — and they could have made much more

of a difference if they had a better songwriting team behind them (in fact, I

see no obstacle to their occupying the same niche as Motown’s Temptations or Four

Tops, had somebody ever set such a goal). But as it actually turned out, although

he would continue recording and charting for quite a long time, Chandler would

never again come close to repeating the success of his debut single,

remaining trapped in his cape and top hat for pretty much the rest of his

life. Like in some generic RPG, the Cursed Duke Of Earl Outfit could only be

removed with a proper Counter-curse, and poor Mr. Chandler never found it in

the short time window when it still could have worked. Now, of course, it is

much too late. |

||||||||

![]()