|

Formally, this might have

been the right thing to do: British kids likely flocked to their TV screens

to watch the leather-clad rock god on Jack Good’s Boy Meets Girl, and rewarded Gene for his effort by putting his

latest record, ‘Wild Cat’, on the UK charts — #21 may not seem like such a

big deal, but for Gene, it was his first chart entry anywhere since late 1957. The only problem, of course, is that

‘Wild Cat’ is thoroughly mislabeled — only those particular British kids

who’d never heard any of Gene’s classic early records could have been fooled

into thinking that this is what real rock’n’roll sounds like. In reality, the

song, recorded already after Johnny Meeks had left the band (with a couple of

totally unknown rhythm and lead guitarists replacing him), is a mid-tempo

sax-led R&B shuffle, a slightly upbeat take on a common bluesy pattern

(see, e.g., Ivory Joe Hunter’s ‘I Almost Lost My Mind’) over which Gene keeps

trying to convince his lady friend to "don’t ever try to tame a wild

cat" — the bitter irony of this, of course, being that the song represents a former wild cat being

completely tamed and docile. The «wildest» part of the song is arguably Jimmy

Pruett’s energetic hammering break on the piano, but even that one sounds

like a feeble shadow of the classic Jerry Lee Lewis country-rock vibe. I

can’t help wondering if Gene himself felt that irony, or if he really thought that on numbers like

these, he was still exorcising his demons with the same verve as he did with

the Blue Caps in his prime, without ever pausing to reflect on how

drastically his sound had changed...

Anyway, the UK kids bought

it (perhaps the black leather outfit proudly displayed on British TV helped

more than the music itself), and this led to a small string of similar hits.

First, the Buddy Holly pastiche ‘My Heart’, taken from the previous album,

went all the way to #15; then came the turn of ‘Pistol Packin’ Mama’,

actually recorded in England, so we’ll return to this a little bit later;

finally, as late as 1961 one of the tracks from this album, ‘She She Little

Sheila’, also nearly made the UK Top 20, showing the world that if the

blasted Yankees were no longer keen on paying their dues to one of their own,

the Brits were still more than willing to take him off those colonial hands.

Even that little patch of hits, however, dried up well before the age of

Beatlemania, so it is useless to accuse the Fab Four and their retinue of

shooting down Gene Vincent’s trans-Atlantic star.

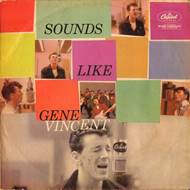

Returning to the album,

I’d say it represents a slight improvement over Sounds Like Gene Vincent

— the songwriting is a little less «obvious» this time around, in that the

various rip-offs of superior composers are at least better masked, and there

are no in-yer-face inferior covers of stuff like ‘Maybellene’ or ‘Ready

Teddy’ whose only purpose is to show how it is possible to play an energetic

rock’n’roll song by leaving exactly 75% of the energy sweatin’ it out outside

the studio door. Also, by this time Gene has gotten a little better with his

completely new type of charisma — that of a smooth, pleasant, occasionally

sharp-tongued young lad who’ll graciously "open doors for little old

ladies" as he sends them off with an ironic witticism or two — and at

the very least, this image is still way preferable to all the Pat Boones and

Frankie Avalons of the new age of teenage entertainment. By the standards of

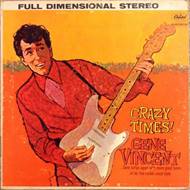

early 1960, Crazy Times! won’t have you growing mush out of your ears,

and that’s already an achievement.

Still, it is hard to believe Gene when he

declares that "I promise crazy times will happen for you and me" on

the opening title track — co-written by Burt Bacharach and Paul Hampton (of

‘Sea Of Heartbreak’ fame), and it may be suspected that the notion of «crazy

times» for Burt Bacharach is not quite the same as it would be, say, for

Screamin’ Jay Hawkins. The «craziest» thing about the track is its fast

tempo, and I keep noticing these really tasty piano breaks from Jimmy Pruett,

who seems to have been the best musician in the band on this particular session.

Vincent, however, sings the main melody in such a smooth and caring tone as

if the girl to whom he was making the promise in question was only just

discharged from the hospital — carefully fixing her in place behind him on

the bike and making absolutely sure not to drive it faster than 20 mph, not

even in the countryside. It’s rock’n’roll, for sure... for kiddies.

This driving association

may actually have been triggered by listening to one of the most symbolic

numbers on the album — ‘Why Don’t You People Learn How To Drive’, credited to

a certain James A. Noble but fully compatible with Vincent’s new vision: a

song that, contrary to just about everything we have learned from the

foundations of rock’n’roll, encourages the listener to take it easy and drive

slow rather than fast: "Well, the wreck on the highway, the traffic’s pilin’ up / I gotta see

my baby and I can’t go fast enough / Why don’t you people learn to drive,

huh? / You know you just might stay alive / Oh, ain’t it a shame, the smoke

an’ the flames / I think you people is nuts". Leaving aside the dark

irony of how this message connects with what would happen to Gene himself on

April 16, 1960, the idea of a rock’n’roll song admonishing people to drive

slow feels somewhere right in the ballpark of Christian rock. I mean, next

thing you know, those damn rockers will start teaching us not to use drugs,

refrain from smoking, and always use protection during intercourse.

Ridiculous!!!

Elsewhere, Gene is

engaging in bouts of self-pity: ‘Everybody’s Got A Date But Me’ is pretty

much defined by its title, and while it would be a stretch to regard the

entire song as a metaphor for the artist’s shriveling career ("Well I’ll find a brand new baby / I don’t

know how right now / They’re all booked up, I’m out of luck / I don’t care

anyhow"), playing it back to back with ‘Be Bop-A-Lula’ or ‘Crazy Legs’

shall certainly hint at a crisis of confidence. It’s still a nice, fast rock’n’roll

number with decent guitar and sax solos, but it’s not even supposed to have a spark of life in

it. It’s more of a "too old to rock’n’roll, too young to die" kind

of thing, and that’s kinda sad for somebody who was just 25 years old at the

time.

That said, at least there’s

a touch of melancholic / ironic humor about most of these tracks, which saves

them from being complete embarrassments. Only two out of twelve songs are

those I’d never ever want to hear again — ‘Darlene’, a slow, stuttery mix of

blues and doo-wop for which Vincent has absolutely no voice, feel, or sense

of phrasing; and ‘Mitchiko From Tokyo’, a corny pop ditty that must have been

inspired by the Crown Princess, but has little to offer as redemption for its

silly stereotypes (and, for that matter, I think that Aneka’s ‘Japanese Boy’

is a great pop song, regardless of

any «cultural appropriation»; it’s only when the song’s primary purpose is to titillate and exploit when it becomes

offensive).

On the other hand, he puts

in a surprisingly uplifting take on ‘Accentuate The Positive’ (the song works

real good with a steady pop beat), sounds tender and sweet without extra

syrup on ‘Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain’, and produces at least one minor

classic in ‘She She Little Sheila’, which, as I already said above, gave him

one more UK hit. The song’s main vocal hook makes it more of a «comic rock»

tune, of course, something in the vein of Larry Williams, but that’s not

necessarily a bad thing. If you can no longer provide a steady adrenaline

punch, might as well put a smile on their faces, right?

Which brings us up to the

paradoxical conclusion: Crazy Times! tries to solidify Gene Vincent’s

new image as that of a «jovial» entertainer, stressing the light-headed fun

and humor in rock’n’roll, while at the same time concealing a subtle internal

bitterness, probably stemming from the artist’s own realization of his fall —

once a true King of all the wild cats, now more of a meek, friendly little

rock’n’roll clown. Ironically, in real life the meek and friendly clown seems

to have still been upholding a threatening image — constantly getting into

fights and gun-totin’ like crazy; at least he had nothing to do himself with

the terrible tragedy of April 16, 1960, in which Eddie Cochran lost his life

and Gene suffered severe injuries — another severe setback to his European

career.

I do believe that Gene’s

last UK hit for 1960, a cover of the old Bing Crosby / Andrews Sisters hillbilly

hit ‘Pistol Packin’ Mama’ which he recorded at Abbey Road in May, right after

his recovery, was intended as a bit of tribute for Eddie — since it borrows

its drum-and-bass intro directly from Eddie’s ‘Somethin’ Else’. It does not

change Gene’s overall comic vibe all that much — the lyrics are delivered in

a joking manner, the sax break is hilarious, the piano line (played by a very

young, pre-fame Georgie Fame) is breezy — but the subject matter seems to be

right up Vincent’s alley, as he was pretty pistol-packin’ himself and sang

the thing with complete dedication. Still, this is pretty toothless

hooliganry; I dare say the song was far more cutting edge back in good old 1943.

To add one final insult to

one final injury, the album was released in several countries (France and Sweden,

among others) under the odd title of Twist Crazy Times! — as if to

suggest that Gene was now influenced by the likes of Hank Ballard or Chubby Checker,

which he was anything but. This would be the equivalent of some subsidiary record

label releasing Fleetwood Mac’s 1977 album as Disco Rumours, just

because anything with the word ‘disco’ on it sells 20% more copies

automatically. Did they even ask Vincent’s permission?.. I seriously doubt

that.

|

![]()