GOLDEN EARRING

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1965–2012 |

Pop rock |

Daddy Buy Me A Girl

(1965) |

Page

contents:

- Just

Ear-Rings (1965)

GOLDEN EARRING

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1965–2012 |

Pop rock |

Daddy Buy Me A Girl

(1965) |

Page

contents:

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Album

released: November 1965 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

3 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) Nobody But You; 2) I Hate Saying These Words; 3) She

May Be; 4) Holy Witness; 5) No Need To Worry; 6) Please Go; 7) Sticks And

Stones; 8) I Am A Fool; 9) Don’t Stay Away; 10) Lonely Everyday; 11) When

People Talk; 12) Now I Have; 13*) Chunk Of Steel; 14*) That Day; 15*) The

Words I Need; 16*) If You Leave Me; 17*) Waiting For You. |

||||||||

|

REVIEW

|

||||||||

|

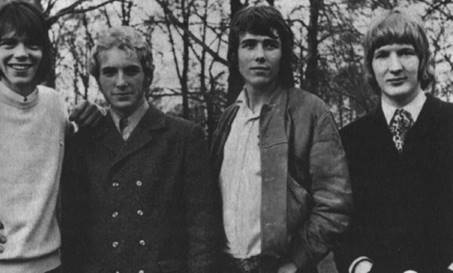

The Golden Earrings’ second advantage, closely tied

in with the first one, was that their several years of original experience

taught them that it made more artistic (and, arguably, more commercial) sense

to write their own material than rely on covering popular hits by their main

influences. One look at the track listing for their debut reveals that all

the songs are written by either Kooymans or Gerritsen or the both of them,

with but one exception (the cover of Ray Charles’ ‘Sticks And Stones’, which

they must have learned from the Zombies’ version rather than the original).

This gave them a serious reputation boost even in the early days, ensuring a

constant presence on the Dutch charts starting from their very first single,

even if they would have to wait eight more bleedin’ years to break into the

international market with ‘Radar Love’. Certainly the effort they made was

admirable — how many first-rate British

bands had there been whose members were prolific songwriters from the very

start of their recording career? Unfortunately, there is one problem: it is not

enough to write your own songs in order to secure your reputation — they

should also have enough of an identity. And 1964–65 were definitely not the

best years for aspiring European rock bands to develop their own identity:

roughly speaking, everybody wanted to be either the Beatles, or the Rolling

Stones, or both of them at the same time with a dessert serving of the

Zombies and the Kinks in between. This is precisely the case of early Golden

Earring, whose material is almost entirely composed of chords, melodies, and

harmonies that any fan of classic British Invasion already knows by heart —

dutifully reshuffled in such a way as to avoid direct plagiarism suits, but

the downside is that most of the songs become the musical equivalent of an

incorrectly assembled IKEA dresser: all the parts are there, but somehow

nothing ever opens or closes properly. A case in point is their debut single, ‘Please Go’.

Beatles, Stones, and Zombies all donate blood on this plaintive mid-tempo

shuffle which diligently goes through nasty-to-soulful key changes, bluesy

harmonica breaks, and folksy acoustic flourishes, all the while pinned to a

ponderous Ringo-style beat. But none of these elements ever really coalesce

into a meaningful hook; somehow, everything is still totally predictable and

there aren’t any real surprises. Frans Krassenburg, the lead vocalist, is

somewhere in between Colin Blunstone and Phil May tonally, effortlessly

switching between the vulnerability of the former and the nastiness of the

latter but in such an apprentice-like manner that I find it impossible to

suspend the proverbial disbelief. Most importantly, though, they simply fail

to find one magic chord, one mesmerizing modulation that would make the song

worth your while. It never gets more memorable than on the opening

"PLEASE!... GO!...", and in a sea of local competition on the pop

market, that’s not much of a selling point. The band did make a conscious effort to showcase

their versatility from the get-go, because the B-side ‘Chunk Of Steel’ (not

included on the original Just

Ear-Rings LP for some reason) contrasts with the A-side by being a

tougher — though still reasonably sentimental rather than just brawny —

blues-rocker, riding a tough metallic rhythm pattern from Gerritsen and

rhythm guitarist Peter de Ronde which has a suitably «industrial» feel to it

(suitably aligned with the song title, I mean), unquestionably heavy for 1965

and more similar to wild American garage bands like The Sonics than any

representatives of British Invasion royalty. Again, though, this chuggy drive

and heaviness are largely wasted on a song that goes nowhere in particular

after it has disclosed its main secret in its first five seconds. Still, it cannot be denied that the band members at

least knew how to play their instruments and had an earnest vibe all around,

so I certainly cannot judge the Dutch public harshly for putting the single

into their own Top 10 — it ain’t great music, but it deserves recognition.

The mild success of the single also allowed Polydor to follow it up with an

entire LP of largely original material, released just a couple months later —

and everything good and bad that I just said about the single applies in

equal part to the LP, which is no big surprise considering that they were all

recorded during the same sessions. Even after three or four diligent listens, not a

single song on Just Ear-Rings

remains in my head (with the exception of ‘Sticks And Stones’, naturally,

that had always been there from the start anyway). The problem is the same —

and it is not the over-reliance on

over-the-Channel influences, not

even the lack of individual identity, it is what I perceive as an inability

to understand what it is that makes this or that particular song click and

come to life. Take the opening number, ‘Nobody But You’. It opens with high

promise, as the drummer pulls off a bit of a Keith Moon, and the lead

harmonies promise old-school Merseybeat ecstasy. But then the bridge section

("when I look at you...")

changes key à la something like the Beatles’ ‘Thank You Girl’,

without, however, managing to set up a different emotional atmosphere, and

even wasting a falsetto twist at the end (something that the real Beatles would never allow

themselves — their higher range was always supposed to be the trigger for

teenage orgasmic bliss). Formally satisfactory, but ultimately hollow and

lifeless. Sometimes the seams are very visible, as they are on the second song, ‘I Hate Saying These

Words’, where I can almost reconstruct the process of songwriting in my own

mind — after a long, painful night listening and re-listening to those

freshly bought copies of Beatles For Sale

and Help!, with echoes of ‘I Don't

Want To Spoil The Party’ and ‘You Like Me Too Much’ still ringing in the boys’

ears. Sometimes the exact sources are more difficult to pinpoint, as with the

third song, ‘She May Be’, which just keeps hammering in its one-chord riff

for two minutes. Inspired by the Kinks, perhaps — or the Byrds? — it’s

actually a somewhat original, rough-rollin’ «garage-folk» thing that, to me,

sounds incredibly stiff and boring. Maybe there’s something off-putting about

the limp and ugly vocal harmonies, but mainly it’s because they have not

found any exciting directions in which to point them. It’s all the more sorrowful considering that the

overall sound of the Earrings is

quite tasteful. There are no attempts here of any kind to pander to the

preferences of «bourgeois» audiences — ringing guitars, pounding rhythm

sections, plenty of raw rock’n’roll drive on the harder numbers and tons of

folk-rock earnestness on the softer ones. No fluffy ballads, sentimental

strings, or Vegasy attitudes; these Dutch boys knew where exactly the musical

truth could be found and they went straight for the right sources. Alas, they

suffered the same curse that so many of their spiritual indie followers have

continued to suffer in the 21st century: they wanted so much, so desperately

to catch that British Invasion spirit by the tail that they forgot the

unwritten golden rule — the spirit only lands on those who carve their own path. It’s no good sitting down

and saying, "I’m not moving from

this spot until I have written a song as good as ‘I Don’t Want To Spoil The Party’!",

because it’s a creative dead end that will either have you transforming into Simeon

Stylites or into Baron Munchausen. In the end, I can certainly respect a record like

this — after all, there is no denying that The Golden Ear-Rings were one of

the very first continental bands to have successfully incorporated the sonic

trademarks of the Beatles, the Stones, the Animals, the Kinks, the Pretty Things,

the Zombies, and the Byrds (yes,

all at the same time!) into one 12-song package. You could write a lengthy Ph.D.

thesis dissecting the record’s influences, or write a thrilling 200-page long

musicological treatise (How I Mastered The

Mid-Sixties’ Spirit Just By Listening To One Lousy Album). Unfortunately,

the one reason why I won’t do either of these things is that I utterly lack

the desire to listen to the album for the fifth time. And for the record,

yes, (The) Golden Ear(-)ring(s) would

get better; but this particular brand of the First LP Curse is a strong one,

rooted as deeply as one’s DNA, and you can never really get rid of it completely.

Medically treatable, yes, but incurable. |

||||||||

![]()