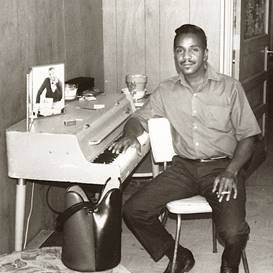

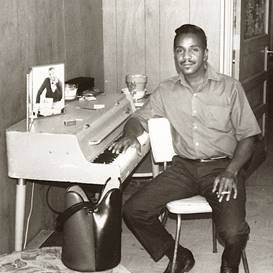

HUEY "PIANO" SMITH

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1956–1981 |

Early rock’n’roll |

Havin’ A Good Time

(1958) |

Page

contents:

- Having

A Good Time (1959)

HUEY "PIANO" SMITH

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1956–1981 |

Early rock’n’roll |

Havin’ A Good Time

(1958) |

Page

contents:

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Compilation

released: 1959 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) Rockin’ Pneumonia And The

Boogie Woogie Flu; 2) Little Chickee Wah Wah; 3) Little Liza Jane; 4) Just A

Lonely Clown; 5) Hush Your Mouth; 6) Don’t You Know Yockomo; 7) Havin’ A Good

Time; 8) Don’t You Just Know It; 9) Well I’ll Be John Brown; 10) Everybody’s

Whalin’; 11) High Blood Pressure; 12) We Like Birdland. |

||||||||

|

REVIEW

|

||||||||

|

In fact,

nothing could be farther from the truth, because Huey "Piano" Smith

did not record just this one silly

novelty song while he could still have a recording contract. Nosiree; he

recorded dozens of silly novelty

songs, and most of them were charmingly catchy — I suppose that the public

only clung on to ‘Don’t You Just Know It’ because it made for just about

perfect family entertainment, a song that parents could freely share

with their kids without having to explain to them who exactly was John

Brown or why guys sometimes refer to girls as "little chickee wha

wha". Furthermore, in his own subtle way he was quite influential, not

just on the further development of the New Orleanian scene (Dr. John, among

others, was a big fan and a reverent disciple), but on, let’ say, the

promotion of good-natured fun and humor for the rock’n’roll idiom in general.

From Roy Wood to the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, every rock’n’roll artist and

band with a bit of a «clownish» streak to them owes at least an indirect debt

to Huey Smith and his rowdy bands of merry-makers. Huey is, in

fact, a classic example of a Fifties’ guy who was able to make the most of

his relative strengths in the face of his many overriding weaknesses. Despite

his "Piano" moniker, it would be a serious stretch to call him a

«great» piano player; next to such New Orleanian prodigies as Professor

Longhair or even Fats Domino, he was neither a virtuoso nor a creative

innovator at his instrument. He could play reasonably well, but there was

nothing outstanding about his barroom style, and didn’t he just know it —

there is not a single moment on these Fifties’ singles when he ever tries to

«show off», as this would probably just result in an embarrassment. He was

not a good singer, either, lacking confidence in his own abilities and nearly

always relying on the various members of his revolving-door entourage. And as

a frontman / showman / wildman, whatever, he allegedly did not qualify at

all, not finding it within himself to bang on those keys with the demented

abandon of a Little Richard or a Jerry Lee Lewis. But he did have

a good sense of humor, and for a while, he could work wonders with it within

the common R&B and rock’n’roll paradigms of the time. Borrowing musical

ideas from the local «Mardi Gras Market», Huey would work them into funny

variations, adding humorous lyrics (with or without sexual innuendos,

depending on the particular corner of that market he wanted to appeal to)

and, with the aid of his singers (His Rhythm Aces at first, then His Clowns once

it became clear that humor would be a permanent ingredient), turning the

numbers into two minute-long vaudeville shows. The style quickly caught on,

and by 1959 Smith had made a name for himself as a national phenomenon, even

if that fame would be very short-lived — yet the overall innocent charm of

the best of those little vignettes feels pretty timeless to me, and may quite

easily be resuscitated at any time, give or take a viral video on TikTok or

whatever. This LP, the

one and only truly solid collection of Huey Smith originals to own, was

released some time in 1959; it includes almost everything he and his bands

released from 1956 to 1958 on Ace Records, with only a few gaps that have to

be sought out on expanded CD releases or separate collections (mostly,

though, they are not very significant, e.g. an instrumental version of

‘Rockin’ Pneumonia’ that was the original B-side of the single). Since Huey

seems to have never been in much of a hurry, the stream of those recordings

was steady, but slow, no more than two or three 45"s for each year, and

even some of those a bit redundant — which just goes to show that coming up

with a nice funny vaudeville tune is a far more difficult enterprise than

coming up with a new 12-bar blues record. Or, alternately, that Huey was

never all that crazy about the studio environment, preferring the hazy

intimacy of the barroom or the sweaty excitement of the ballroom. The first of

these singles, still credited to «Huey Smith And His Rhythm Aces», already

fully succeeds in establishing a good mood — ‘Everybody’s Whalin’ is a merry

piano-and-sax driven dance tune where the vocals don’t matter much, and the B-side

is a fast-paced reworking of the old folk classic ‘Little Liza Jane’ with a

hyperactive electric guitar taking a historical lesson from the banjo. The

common link between both songs (and, in fact, almost everything that followed

as well) is a muddy style of production where the drums are inexplicably put

out up front and everything else, particularly

Huey’s own piano, is completely overshadowed by the wildly crashing and

smashing percussion. This does often happen with New Orleanian artists for

some reason, but Huey Smith’s records are especially affected by this

approach; you will need to learn to overlook it in order to enjoy the music. The big break

for Huey Smith came with his second single, whose title a lot of us will

probably recognize without ever remembering the name of the original artist —

‘Rockin’ Pneumonia And The Boogie-Woogie Flu’, now credited to «Huey Smith And

The Clowns» and coming in two parts (the second, on the B-side, is just an

instrumental version of the A-side and honestly dismissable). It not only

introduces the «Huey Smith Opening Piano Flourish», which would subsequently

grace a lot of his other songs, but does something much more important — it

is really one of the first «meta» treatments of the rock’n’roll lifestyle in the

history of recorded music. Up to that time, most of the rock’n’roll numbers

whose subject matter was rock’n’roll itself treated it with a straight face —

anthemically, reverentially, or with a «wild wild fun» attitude. Even a

decidedly clownish band like the Coasters would still sing a song like ‘That Is

Rock’n’Roll’ as if they were putting the genre on a holy pedestal. With ‘Rockin’ Pneumonia’,

the tables were turned — Huey’s singers (his own barber Sidney Rayfield and the

legendary Mardi Gras Indian "Scarface" John Williams) sang the song

not from the point of view of the young rebellious teenager, but from that of

an outside old geezer, envying the young man his bit of fun but unable to

properly participate in it due to age differences and ailings (the song was written

in the midst of the infamous 1957-58 influenza pandemic, which should

probably endear it to us even more in the Covid Age). Musically, the song

does indeed sound like it wants to

break out into all-out rockin’ mode, especially with that nagging sax riff doing

its amusing «mini-jumps», but is constantly hampered by the players not

understanding where to go next... and this, of course, only works to the

advantage of the general message: "I

would be runnin’ but my feet’s too slow". No wonder all those old

geezers of rock’n’roll come under the song’s charm later in life — Aerosmith

covered it in 1987, and Deep Purple waited all the way to 2021 (!). The huge

success of ‘Rockin’ Pneumonia’, unfortunately, could not stop Huey from

falling prey to self-plagiarizing: the next single, ‘Just A Lonely Clown’, coupled

the exact same melody of ‘Rockin’ Pneumonia’ with a much less interesting

message and rather annoying falsetto «clownish» ad-libbed vocals — the humor

was still there, but the ironic deconstruction of the rock’n’roll idiom was

replaced by slapstick. Fortunately, realizing his own mistake, he quickly

bounced back with ‘Havin’ A Good Time’, which gives this LP its title and is

fully musically adequate to its own — a cheery manifesto of the supreme rule

of all-night partying, nothing more and nothing less (although I like the

nearly instrumental B-side, ‘We Like Birdland’, a bit more — it actually gives

more space to Huey’s piano playing). And then it finally

came — the one song that, for a while, turned Huey Smith into a household

name and still remains his well-worn-out visiting card for most people who

remember that name at all. ‘Rockin’ Pneumonia And The Boogie Flu’ may have

been his major gift to the musical world, what with all the innumerable

covers throughout the decades, but ‘Don’t You Just Know It’ was his crown

contribution to The People, a song so simple, silly, and inescapably catchy,

it should probably be one of the first on that love-it-hate-it list which

leads directly all the way to ‘Baby Shark’. Does this really make one a

hypocrite to shudder at the idea of ‘Baby Shark’ being among the most watched

YouTube videos of all time, but then to go «oh, cute!» at the idea of ‘Don’t You

Just Know It’ having been a smash hit single back in 1958? Perhaps it does

and perhaps it does not, but I’m pretty sure that ‘Don’t You Just Know It’,

for all its simplicity, repetitive structure, and manipulative treatment of

the listener, has one thing that ‘Baby Shark’ doesn’t — personality. What keeps it alive and charming is that irreplaceable,

unimitable, exclusively New Orleanian good-naturedness. People usually

covered ‘Rockin’ Pneumonia’ and not this song not so much because the former

was «deeper» (although it was), but because it did not have nearly as much of

that Mardi Gras spirit — the call-and-response vocals, the «deep male» vs. «high-pitched

female» dialog, the clownish, but sincere ah-ha-ha-ha’s and follow-ups (even

today, I am happy to see that the Internet is regularly hosting discussions

on whether the vocals go dooba-dooba-dooba-dooba

or gooba-gooba-gooba-gooba; my semi-professional

phonetic opinion is that, for some reason, they have a very back-slanting u in there, which makes [duba] feel like [guba], though this still needs to be checked with a proper

spectrometer). Anyway, this is really the kind of tune that can only be made

justice to by the likes of Dr. John, and even then, preferably some time

close to the Epiphany. Not that the

song is all that simple, you know;

honestly, I would request a second opinion before using it in the curriculum as

part of six

lessons in the New Orleans Rhythm & Blues unit, where students are

supposed to "learn the musical

devices “call and response” and “echo” and how they appear in instrumental

and vocal music". Particularly suspicious is the contribution to Common

Core State Standard RL.5.4 "Determine

the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including

figurative language such as metaphors and similes" — hats off to the

brave professor who will have to deal with phrases such as "I can’t lose with the stuff I use",

"Ya got me rockin’ when I ought to

be rollin’", and, particularly, "Young girls in trouble the tighter they squeeze", trying to

explain their figurative language without getting reported to the dean’s

office. Really, one probably shouldn’t push one’s luck too far. One should not totally

ignore the B-side, either: I am pretty sure that ‘High Blood Pressure’, whose

own mid-section borrowed heavily from Elvis’ ‘All Shook Up’, in its turn, may

have been a subconscious influence on AC/DC’s ‘High Voltage’ years later —

just compare the way Bobby Marchan sings "I get HIGH... blood pressure" to Bon Scott’s chorus. And why

should we get too surprised? There had always been a pretty large comic

streak to AC/DC’s early material, and enough of that New Orleanian influence

had seeped in to Australia anyway; it is precisely the boys’ not taking

themselves too seriously as Rock Gods that still endears them to our heart. Fortunately,

the follow-up single to ‘Don’t You Just Know It’ was more of a variation on

its success than a straightahead repeat of the melody, as it was with ‘Just A

Lonely Clown’: ‘Don’t You Know Yockomo’ is just a pure bunch of nonsense,

throwing together every phonetic symbiosis known to pop music ("hidey-hidey-hidey-ho", "reet-petite", "ting-a-ling", you name it) and

advancing the tempo just a bit to generate even more excitement. Even so, I

suppose they went over the top here with the lyrics — the song turned out way

too difficult for the kiddies, blew that family entertainment value and ended

up forgotten. In any case, I’m a bigger sucker for the B-side, ‘Well I’ll Be John

Brown’, which puts a wicked rhythmic twist on the 12-bar structure and rounds

it up with popularizing an allegedly common Southern expression whose

expressiveness can only be compared with Katharine Hepburn’s spirited "Christopher Columbus!" from Little Women. Unfortunately, the LP came out too early to include Huey’s

best song of 1959, which somehow fell through the cracks, so we shall have to

mention it separately. ‘Genevieve’, with "Scarface" John Williams

taking lead, is a somewhat more serious than usual mid-tempo blues-cum-R&B

number with a rising-falling chord pattern that presages Howlin’ Wolf’s ‘Killing

Floor’ several years later — and, incidentally, also a song in which you can

pretty clearly hear the roots of the Beatles’ ‘Hey Bulldog’: make just a

couple subtle changes to that

opening piano riff and there you go. The song is just a small step away

from becoming «soulful», but that is certainly not the direction in which Huey

generally wanted to go — the B-side, ‘Would You Believe It (I Have A Cold)’,

promptly returns us to the safe old comic grounds. Then again, even Louis Jordan

had his «serious» detours every now and then. In the end, it’s

all too easy to dismiss Huey "Piano" Smith’s «Clowns» as a

lightweight novelty act — but let me tell you this: I’d much rather take a New

Orleanian lightweight novelty act from 1958 over any lightweight novelty act

that covers the time span from Woodstock to TikTok. At least this novelty act was feeding on the

essence of the most fresh and exciting kinds of popular music around (R&B

and rock’n’roll), had a modern and creative approach to its music, and, most importantly, seems to have been

operating under the banner of, well, just havin’ a good time, rather than

attain fame and fortune at the cost of losing one’s dignity. |

||||||||

![]()