|

And most

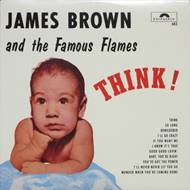

importantly (if also most subjectively), Think!

is also the first James Brown album which I am able to appreciate in toto, from top to bottom. The rocking

numbers, the poppy ditties, the ballads, the doo-wop, even the oldies — each

and every song has something to offer, something at least mildly interesting

and attention-grabbing to stand out in memory. The contrast with Please, Please, Please and Try Me!, both of them so much longer

and so studded with filler, is so sharp, in fact, that I made several

attempts to understand what it was exactly that might have caused such a

difference around late 1959 / early 1960, and still came up empty-handed.

Most likely, there was no single specific catalyzer here, but rather just a

process of gradual ripening. For four years, James Brown and the Famous

Flames were trying to find and define their own sound, that special vibe

which could put them on top of, or at least aside from, everybody else while

also holding enough commercial potential. With Think!, they finally found it.

Perhaps that

one truly fateful day could be determined as June 27, 1959, when down at Beltone

Studios in New York Andy Gibson produced the first single to be included on

this LP — ‘Good Good Lovin’. The song is an odd mix of influences: Bobby

Roach’s seductive opening guitar licks sound like a nod to surf-rock, the

main melody is a sort of sped-up Chicago blues, and the groovy tempo and

lively sax break give it a bit of a Coasters feel, with a touch of the «comic

R&B» vibe. But the overall feel of the song, with Brown’s hysterical

vocal driving his players on and on, is exclusively James’ — a mix of rock

energy, pop playfulness, and soul passion completely unmatched by any other

artist at the time. It’s catchy, it’s danceable, it’s fun, and it’s got the

spirit. (For a long time, I also thought it got great lyrics – "good lovin’, good lovin’ made me feel so

bad" – before finding out that he really sings ‘glad’, not ‘bad’, which

makes things far more boring). The song, heralding a new, self-assured sound

for the Flames, should have been a big hit — but, for some mysterious reason,

ended up as yet another flop. Fortunately, it did not dissuade Brown that

they had something really good going on here, and by the time the band

reconvened in Cincinnati for their November recording sessions, he had quite

a few ideas in his head on how to properly follow up the vibe of ‘Good Good

Lovin’ and really make it happen.

‘I’ll Go Crazy’, the first single to be released from those sessions,

also opens with a seductive guitar lick (this time, more of an opening — and,

later, closing — fanfare than a surf-rock chuckle), but the mutations to the

blues idiom that they injected on ‘Good Good Lovin’ are even stronger this

time. The way the song’s memorable bluesy riff gets capped off by the pompous

guitar/brass one-chord fanfare could be something from the textbook of B. B.

King (although he would probably play it slower and with more of that Vegasy

pomp), but once the vocals enter the picture, it’s 100% James Brown rule all

along. Most importantly, listen to the wonderful shadowing of James’ vocals

by the Flames — "if you leave me...", smoothly flowing right into

"leave me-e-e-e-e...", then "I’ll go crazy", echoed by

"oh yeah!", and then "’cause I love you..." – ("love

you!") — "love you..." ("love you!"), and James’

final flourish of "I love you too mu-u-u-a-a-a-i-i-ich".

That is the kind of vocal richness that ensures this song, as popular as

it eventually became, would never ever be performed better by anybody else.

(Just relistened to the Moody Blues cover from 1965 and, with all love and

respect for Denny Laine, it’s a total joke next to the original). However,

here as in many other places, I would not emphasize the «soul» aspects of the

performance — it is, in my opinion, more of a «touch of soul» which gets

converted into a gripping pop hook. Listening to the song never really makes

me believe in Mr. James Brown as somebody capable of going crazy if somebody

whom he loves too much ends up leaving him. Rather, it makes me believe in

Mr. James Brown as somebody capable of going crazy... period. But that’s alright, works for me too. "You got to live for yourself, yourself and

nobody else" is the real message of the song; I’ve never been able

to buy the message of James Brown as a heartbroken, vulnerable guy whose life

could have been made miserable by a member of the opposite sex — but the

image of James Brown as a self-obsessed, maniacal guy whose life could be

dominated by violent emotional flares is totally believable (even if that

image, too, had been quite meticulously constructed and calculated for

maximum public appeal).

‘I’ll Go Crazy’ did what ‘Good Good Lovin’ failed to do and restored

Brown to the R&B charts, going all the way up to #15, but the ultimate

comeback was achieved with ‘Think!’ — which, as a single, was released

already a couple months after it had appeared as the opening title track on

the same-titled LP. Now this is an interesting case because the song was not an original James Brown

composition: it was written by Lowman Pauling, the guitar player for The

"5" Royales, and originally released by his band in 1957 (the same

year which also produced ‘Dedicated To The One I Love’, arguably their most

famous song because of the later Mamas & Papas cover). The original is a nice

enough blues-pop ditty with inventive stop-and-start elements and some

impressive (for the time) guitar work from Lowman — but really, it mainly

makes sense to listen to it just to be able to better appreciate the tectonic

changes brought on by the James Brown treatment. In Pauling’s hands, the song

is merely a tepid, passable dance-hall number, a piece of friendly background

entertainment, whose occasional interruptions by that shrill, sharp blues

guitar come across as a novelty moment. In comparison, Brown reinvents the

song to the point of making it barely recognizable — I’m actually impressed

that he gallantly did not add his name to the credits, since from a moral, if

maybe not legal, standpoint at least, he had every damn right to do so.

I mean, ‘Think!’ just kills — and I even like this studio version more

than the one on Live At The Apollo,

where it would be sped up to a ridiculous, «Ramonesque» tempo that probably

worked like a charm for the audience but does not do the song proper justice

on record. Here, the tempo is just right — still quite fast, but enough to

let you soak in and digest all the crazy stuff going on, starting with Nat

Kendrick’s complex and metronomic drumming pattern and ending with the

equally tight and metronomic brass riff, something the likes of which simply

did not exist before the song — count it as a natural precursor to all the

funk and jazz-rock patterns from the mid-Sixties and onward. Together, the

percussion and brass whip up an atmosphere of perfectly controlled hystrionic

frenzy, giving James the ideal backing for his own vocal hysteria. Taking the

punctuated breaks of "think!..,

think!.., think!" from the "5" Royales original, he

evolves them further into veritable boxing punches: "THINK! – About the good things!"

... "THINK! – About the wrong

things!" ... "THINK! –

About the right things!" — before that lady leaves him, she’ll

probably be all bruised up, if not physically, then at least emotionally.

Nothing in the entire R&B scene of 1959–60 rocked quite as hard as this

song — nobody on the scene even dared to kick that much ass, let alone having

the musical chops to back the aggressive, frenetic energy with tight-as-hell

musicianship.

And while the singles, naturally, attract the lion’s share of attention,

the rest of the album hardly strikes me as just filler, either. The same

frenzy that permeates the dance numbers can also be seen in (at least some

of) the ballads: thus, ‘Wonder When You’re Coming Home’ builds up a really

dark mood with its combination of deep bass, somber, echoey backing vocals,

and Brown’s own tragic-hero delivery which, for two and a half minutes, turns

him into sort of an R&B Tristan, waiting for his Isolde on his dying bed.

The Isolde in question might be identified as Bea Ford, who briefly worked

with Brown as a supporting vocalist — before retiring after Mr. Dynamite

knocked her up — and is given a chance to shine on another colorful blues ballad,

‘You’ve Got The Power’, where her smart-and-smokey voice forms a great

counterpart to James’ own. Lyrically and musically, it seems to be a fairly

straightforward declaration of mutual love, but with all those weird

overtones and modulations, you always get the feeling that there is something

deeper and darker going on here, and that there may be quite a few

circumstances in their love life those two are keeping from each other...

Even something as superficially flat-footed and simplistic as ‘I Know

It’s True’ with its lyrical minimalism (each verse consists of four

repetitions of a single line such as "do you need someone to love you?") is made exciting — this

time, by Nat Kendrick, who adds a deliciously fussy (but metronomically

precise, as always) hi-hat pattern on top of the regular beat; but also by

James, whose soaring delivery of each third line really makes the difference.

And even when Brown chooses to cover an oldie from the American Songbook

(‘Bewildered’), he adapts it to the Flames’ new style so well, you’d never

guess the song’s origins — lots of artists had their day with ‘Bewildered’

before, but nobody got the idea to sing it like an actually bewildered

person: listen to the

Ink Spots deliver those first lines like a bunch of angels, then revert

back to James Brown to have them delivered from the mouth of a madman.

Without going into details on the other songs, let me just generalize: Think! is where the James Brown

machine really starts hitting on all

the cylinders all the time, rather

than some of the cylinders some of the time. The backing band

here becomes more than a backing band — you can hear and appreciate all the

individual talent and all the initiative, from Nat Kendrick’s highly

inventive and unpredictable drumming patterns to the brass section’s

combination of almost military discipline with catchy riffing. And Mr. Brown

himself realizes that his power lies not in the source material, but in the

creative touch applied during the recording session — and, of course, in

taking every song’s vocal portrait to the highest level of expression (which

is not just about screaming his

head off: when necessary, he can sink to the lowest depths of soul just as

fine as he can rise to the utmost heights of it). The result is a

thirty-minute long blast of non-stop energy which, one might argue, would

never be topped again — musically, Brown’s albums would of course get more

complex, innovative, and interesting over time, but in terms of sheer

enthusiasm, ecstasy, and professionalism, Think! really gets the goat; I like to imagine it as Brown’s

equivalent of the Beatles’ Hard Day’s

Night — lightweight, naïve, and utterly perfect as far as pure,

fresh, untapped musical genius is concerned.

|

![]()