|

It does contain

three tracks that will be fairly familiar to any serious fan of Sixties’ rock

who may not ever have heard even one Jimmy Reed original: the singles ‘Baby

What You Want Me To Do’ and ‘Big Boss Man’ have been covered by just about

everybody, and so was the non-single ‘I Ain’t Got You’, extracted here from a

much earlier session in 1955 to fill up empty space on the LP and somehow

catching the eye of both The Animals and The Yardbirds (and then, later,

Aerosmith). The song, by the way, was not written by Jimmy, but rather by

Vee-Jay’s producer Calvin Carter, which might explain why it is the only song

here that does not quite sound the

same way as ‘That One Jimmy Reed Song’ — amusingly, the first commercial

release of the song by Billy Boy

Arnold actually sounds more like generic Jimmy Reed than Jimmy’s own

recording, which unexplainably remained in the vaults for five long years.

You can easily see the UK kids falling under its spell — the weird time

signature, the threatening stops-and-starts, the ominous harmonica howls

after each repetition of the title (usually converted to guitar howls in

those UK versions), and, of course, the delectable mystery of this whole

situation. "I got women to the

right of me, I got women to the left of me, I got womens all around me... but

I ain’t got you!" What is it, exactly, that makes the «you» in

question so damn special? It’s a cool, swaggery celebration of life’s

luxuries, each line of which is undercut by the double bang-bang! of realization that there’s actually more to life than

"Eldorado Cadillacs" and "charge accounts at Goldblatt",

though the protagonist cannot quite figure out what and why.

It’s a cool

song, but one might also add that it is not very much in line with Jimmy

Reed’s essence. Jimmy Reed might have been reasonably well off with all of

his sales in the Fifties (although I guess he must have squandered all his

earnings on booze anyway), but his artistic persona is not fairly well

associable with life’s luxuries — his is the role of the little man, the

simple man quietly nibbling away at life’s simple pleasures and swatting away

life’s minor troubles. The quiet worker ’round the clock whose "big boss

man" certainly can’t hear him when he calls, because he’s too afraid to

call him in any voice louder than a toothless whisper. For the sake of

accuracy, ‘Big Boss Man’ was not written by Jimmy either (it is credited to another

of his producers and Luther Dixon, the professional songwriter responsible

for the breakthrough of The Shirelles), but unlike ‘I Ain’t Got You’, this is a song tailor-made for him,

and it’s refreshing to hear him borrow the rhythm of Chuck Berry’s ‘Memphis,

Tennessee’ for it, rather than reuse the same mid-tempo ka-CHUNK-ka-CHUNK 12-bar blues beat that crops up pretty much

everywhere else.

The funny thing

about ‘Big Boss Man’ is that almost everybody who covered it actually treated

the song as a rebellious anthem — Elvis, in particular, sounded and looked

like he was really going to tear

his own "big boss man" a new one; here, though, it is crystal clear

that Mr. Reed is just grumbling "you

ain’t so big, you’re just tall, that’s all" under his breath, scared

to death to throw it in the man’s face, which, alas, is usually a much more

gritty reality for us than the opposite. If you listen real hard, you can

hear Mary "Mama" Reed faintly echo Jimmy’s lyrics in the background

— she was, perhaps, just cueing him in, but she ends up putting a sort of

«family touch» on this intimate protest song, the loyal partner supporting

her struggling proletarian working man from afar but just as helpless to

remedy the situation. In this particular case, I might dare to suggest that

nobody ever truly improved on the original ‘Big Boss Man’ (although I’m

becoming pervertedly partial to the ridiculous 1985 cover by B. B. King

which pretty much sets the original lyrics to the melody of ‘Billie Jean’!! —

really, no other decade excelled as much at trying to turn Dumb and Absurd

into Cool and Stylish for subsequent generations to hypothesize about

potential alien infiltrations or undetected viruses... but we’re getting off

topic). At least when it comes to brutal cowardly honesty, Jimmy here is our

fellow man.

As for the

mid-tempo ka-chunk, ka-chunk, it, of course, opens the record

with what has arguably become the most widely covered Jimmy Reed song of all

time — ‘Baby What You Want Me To Do’. Here’s a funny bit of trivia: everybody always sings "you got me doin’ what you want me, baby

what you want me to do", while in fact the original lines make a

little more sense as Jimmy goes "you

got me doin’ what you want me, baby why you want to let go?",

indicating a little more agency on the part of Jimmy’s dissatisfied

sweetheart. But, of course, there’s no getting away from the fact that the title of the song has never been ‘Baby

Why You Want To Let Go’, so the source of the confusion is clear, as is the

natural attraction of the interrogative phrase to its affirmative

counterpart.

And the

phrasing does matter here. There

are literally dozens of Jimmy Reed songs that all sound exactly like ‘Baby

What You Want Me To Do’ – at least three or four of them on this very album —

but instead of getting randomly and evenly covered by subsequent generations

of admirers, they are all forgotten while ‘Baby What You Want Me To Do’

trudges on and on and on. Even The Everly Brothers, who by 1960 must probably

have realized that blues-rock would never become their forte, rushed out to

produce their own version of the song as soon as they heard it. Apparently,

all it takes is a little fiddling with the generic structure of the AAB

pattern to get a specifically «nagging» feeling — got me running, got me hiding, got me run, hide, hide, run, anyway

you want to... — and somehow the song grows itself an extra claw and

turns from instantly forgettable to permanently memorable. For Jimmy, it was

really a lucky fluke; for the world, it was the arisal of a new standard,

which, unfortunately, then went on to sprout like a weed. Maybe ‘Stairway To

Heaven’ is the most overplayed song

in the world — who knows — but I know for sure that I have never had to suffer

through as many totally unnecessary and superfluous covers of ‘Stairway To

Heaven’ than I did of ‘Baby What You Want Me To Do’. Ironically, not a single

of these covers ever managed to improve on the original, either.

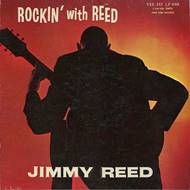

That said, the

bulk of Found Love is more akin to

the title track of Found Love —

which has the exact same melody as ‘Baby What You Want Me To Do’, only a tad

sped up and, this time, following the conventional AAB pattern to a tee. It

is true that a bit of effort, if you decide to delve deeper into the lyrics,

may be rewarding here. The already quoted Al Campbell from the AMG states

that "the title track is

particularly notable, as it contains a one-note harp wail that proves to be

vibrant, heartfelt, and timeless" — indeed, it is very vibrant,

though I’m not so sure about ‘timeless’ (well, since I am still listening to

it today, maybe it is timeless);

but as for ‘heartfelt’, I would guess this word should decode as «imbued with

sincere positive emotion», which would agree rather well with the first line

of the song ("I found true love,

one worth waitin’ for") but only if you prefer to totally ignore the

second — "I’m gonna sign it to a

contract, you won’t find one little flaw". That’s right, Jimmy Reed did have a cynical sort of humor, well

confirmed in the second and last verse of the song: "It’s hard to believe the condition the

world is in / You can’t trust nobody and girl you know it’s a sin".

Indeed, the

entire album sort of implies that even if Jimmy Reed did find love, he sure

as hell ain’t got no idea what to do with it, or even how to keep it — all of

those songs are about family quarrels, adultery, eloping, begging for

forgiveness, and other things typical of the dysfunctional mind. Ten of them

— everything, that is, except for ‘Big Boss Man’ and ‘I Ain’t Got You’ — also

have the exact same ka-chunk ka-chunk melody, the subtle differences provided

by speedier or sluggier tempos and by whether the bass player wants to get a

little more creative or just get paid by the minute. I won’t deny that there

may be a certain therapeutic effect here — some people who feel like shit and

need to get their rocks off without being tainted by pathos or pretense might

find this particular way to waste thirty minutes to be their personal path to

healing. But generally, all you need from Found Love are three songs — well, four if you throw on the title

track as a representative of Reed’s ironic attitude to life.

|

![]()