|

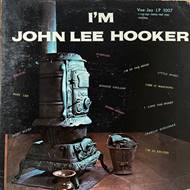

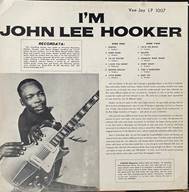

Consequently,

while no blues lover’s collection will ever be representative without a

serious compilation from Hooker’s early days on Modern (The Legendary Modern Recordings 1948–1954 will probably suffice),

we shall begin our journey through his long (and fairly uneven) recording

career with the opening of the LP era; for Hooker, this happened in August

1959, with his current Chicago label of Vee-Jay Records putting out a

selection of A- and B-sides stretching all the way back to 1955 as I’m John Lee Hooker, his very first

LP — as the title does indeed suggest.

Hooker’s

association with Vee-Jay was far from accidental. In the second half of the

1950s, when it came to blues, Vee-Jay sort of established themselves in

Chicago as the «rebelliously unsophisticated», «proto-punk-blues» alternative

to the more «cultured» environment of the Chess label — this was hardly

intentional, but birds of a feather do tend to flock together, and Hooker

eventually ended up on the label in 1955 through his connection with Jimmy

Reed, who had already been cutting singles for Vee-Jay since 1953. In fact,

Jimmy himself accompanies Hooker on harmonica on his earliest singles for the

label (one of those B-sides, ‘Time Is Marching’, is included on the LP), and

it is no coincidence, either, that Jimmy’s own debut LP on the label,

released one year earlier than Hooker’s, bears the title of I’m Jimmy Reed.

In stark

contrast to much, if not most, of his Modern era output, when it was usually

just Hooker and his guitar, in Chicago, following Jimmy’s example, the artist

quickly got provided with his own house band — which usually included Reed’s

friend and companion Eddie Taylor on second guitar, as well as a rotating set

of drum and bass players and, occasionally, a bit of piano backup. He did not

abandon his classic solo style completely, but for the most part, he confined

it to re-recordings of his best known oldies, which he began producing around

1958–59: this album, in particular, includes new versions of ‘Boogie

Chillen’, ‘Hobo Blues’, ‘Crawlin’ King Snake’, and ‘I’m In The Mood’ — all of

these had been originally issued on Modern in 1948–1951, yet instead of

properly «modernizing» them with a backing band, Hooker remade them in his

traditional style. I am not exactly sure why; perhaps the people at Vee-Jay

asked for this themselves, afraid that other labels might make more money on

their former star’s back catalog than Vee-Jay would make with his new stuff.

Once again,

purists will probably insist that these re-recordings are nowhere near as

«authentic» as the originals, but from an unbiased position this is

debatable. Obviously, the sound quality for a 1958 recording would be objectively

superior to a 1948 one. Also, over those ten years Hooker’s voice — arguably

the number one source for his legend, with his guitar playing skills strictly

stuck at number two — had gotten at least an octave deeper and even more

intimidating than it was in the late Fourties, which works wonders for his

inherently dark blues material. On the other hand, there is certainly a

chillin’ crudeness about the early recordings that makes them feel more

earthy and Neanderthal than the slightly more melodic, more overtone-relying

sound of the Vee-Jay era. All I can say is that it’s fun comparing the two,

and no fun debating which ones are more «authentic» and which ones more

«commercial». One other thing that I have noticed is that the new versions

are typically just a tad faster — this might be just a technical effect of

the mastering process, but could just as well be a side effect of John Lee

Hooker going more «rock’n’roll» as a result of his constant playing with a

band.

In any case,

while the re-recordings all seem quite decent to me and fully deserving of

being part of the Hook’s legend, they still reflect a chunk of his older,

pre-Chicago life. His new life truly

begins with the lead-in track on this album, simply called ‘Dimples’. Who

didn’t know ‘Dimples’ in the early Sixties? Everybody knew ‘Dimples’. The

Animals did a great version of ‘Dimples’ that, in my opinion, was in many

ways superior to the original — but inevitably lost some of its rowdy caveman

spirit. "You got dimples in your

jaw – you my babe, I got my eyes on you". With this song, Hooker

showed that he was not above crossing over to the pop market — without sacrificing

an ounce of his bluesy authenticity. For all of Jimmy Reed’s appeal to the

unsophisticated, pop-loving crowds, this

is faster, catchier, and farther removed from the stereotypical 12-bar blues

formula than pretty much anything Reed did at the time. If not for Hooker’s

scary, growling, stalker-ish voice, this could have been real big with the

kids — as it is, the recording was probably creeping out most of the

conventionally-minded teenagers, not to mention the parents, back in 1956.

(Come to think about it, with current attitudes it would have probably been

creeping out most of the young people in 2022 just as well).

Transitioning

to the ‘Dimples’ style wholesale would be too much even for Hooker at the

time, though; most of the other recordings that Vee-Jay selected from his 12

or so singles recorded between 1956 and 1959 are more conventional and Jimmy

Reed-ish, though on the whole, Hooker favored faster tempos than Jimmy. A

typical example is ‘I Love You Honey’, which was a minor R&B chart success

for Hooker in 1958: strong, prominent boogie bass — free-flowing, old-school

piano accompaniment from Joe Hunter — and a nagging, insistent vocal that

sounds a bit like Reed (but on fewer drugs and with more teeth in his mouth,

metaphorically speaking). It’s a pleasant track, but it has neither the

voodoo magic of Hooker’s solo recordings, nor the dark pop enchantment of

‘Dimples’.

Much improved

is something like ‘Maudie’, recorded about a year later, which departs from

the same territory as ‘I Love You Honey’, but features a much stronger Hooker

presence — here, Hooker’s ‘Boogie Chillen’-derived rhythm guitar, sounding

like a knife rhythmically sharpened on stone steps, is far more prominent,

and his voice is far deeper and more threatening (that "Maudie, why did you hurt me, I love you

baby, you been gone so long" bit should have sent any real life

Maudie running to the nearest police department). Melodically, there is

absolutely nothing here in 1959 that hadn’t already been done two hundred

times earlier, but it does a good job of polishing the Hooker formula to a

shinier state than ever before — that guitar-voice combo, with just a tiny

bit of echo and a solid metronomic rhythm section putting some meat on the

bones, could not be beaten even by such Chess competition as Muddy Waters.

Most of the

other songs (including bonus tracks from the same era that can be found on

some CD editions) predictably recycle the same formula; the rhythmic

peculiarities and poppy geometry of ‘Dimples’ are more of a lucky exception

in this case than a standard example of Hooker’s creativity. But if we

refrain from worrying about the monotonousness and prefer to instead

concentrate on the impact of the general sound, Hooker’s uniqueness quickly

comes through even after he has been placed in the same general musical

context of the 1950s’ Chicago blues band sound.

What I mean is,

where Muddy entices us with his swagger and cockiness, while Howlin’ Wolf

comes across as a theatrically malevolent demonic presence from the red-hot depths

of Hell itself, John Lee Hooker plays the role of that grim, moody, silent,

mysterious loner in the corner, mumbling out something frightening, if barely

comprehensible. His is less of an "I’m gonna come out and get you!"

or an "I’m gonna rule the world with my evil powers!" vibe than a

"Don’t mess with me, leave me alone to brood" vibe. Stuff like

‘Dimples’, in a way, is the spiritual predecessor to Ian Anderson’s

"sitting on a park bench, eyeing little girls with bad intent"

theme — if there is one old bluesman I could easily identify with Tull’s

Aqualung, it would be John Lee Hooker. Sure enough, it might be a much creepier vibe than Muddy’s or

Wolf’s, but if the blues ain’t about being creepy, then what the hell is it

about in the first place? If you want to keep your mind all clean and

sanitized, just stay away from these dudes altogether.

|

![]()