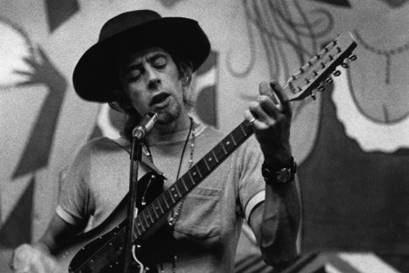

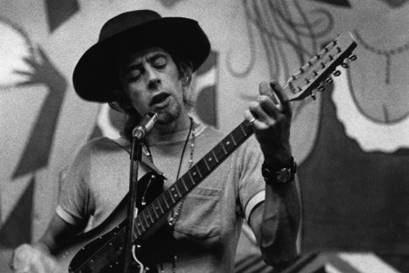

JOHN MAYALL

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1964–2022 |

Classic rhythm'n'Blues /

Blues-rock |

Crawling Up A Hill (1964) |

Page

contents:

- Plays

John Mayall (1965)

JOHN MAYALL

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1964–2022 |

Classic rhythm'n'Blues /

Blues-rock |

Crawling Up A Hill (1964) |

Page

contents:

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Album

released: March 26, 1965 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) Crawling Up A Hill; 2) I Wanna

Teach You Everything; 3) When I’m Gone; 4) I Need Your Love; 5) The Hoot Owl;

6) R&B Time (Night Train / Lucille); 7) Crocodile Walk; 8) What’s The

Matter With You; 9) Doreen; 10) Runaway; 11) Heartache; 12) Chicago Line;

13*) Crawling Up A Hill; 14*) Mr. James; 15*) Crocodile Walk; 16*) Blues City

Shakedown; 17*) My Baby Is Sweeter. |

||||||||

|

For

most people in the world — and far be it from me to blame them — the name

«John Mayall» begins and ends with the Bluesbreakers

album from 1966, though may of the same people might probably have a vague

idea that «John Mayall» was more than a one-time sideman for Eric Clapton,

and that he probably played the

blues somewhere out there before 1966 and most likely continued to play the

blues after 1966. Let us, therefore, begin from the beginning and focus our

attention on the «before 1966» thing — because, in fact, Bluesbreakers With Eric Clapton was only the second LP to come out under the name of John Mayall, while the

first single to come out under the name of John Mayall was actually released

in 1964, around the same time Eric cut his first records with the Yardbirds. |

||||||||

|

If there was one

large problem with being John Mayall in 1964-65, then it was the exact same

one as with Alexis Korner, of Blues Incorporated. Both were decent and

sincere musicians, passionate about promoting and developing blues and

blues-rock in the UK — but both were simply too old: Korner was born in 1928, and Mayall in 1933, which makes

them at least a decade or so (in Korner’s case, a decade and a half) older

than the average Beatle or Rolling Stone — and back in the early Sixties,

this mattered, a lot, and not just

because of the agist bias of the younger generations. What this meant was

that Korner and Mayall cut their playing teeth in the Fifties, an age of

relative restraint and repression, when «wildness» was not yet fully accepted

as a normal state for performing popular music. Rock’n’roll artists could be

«wild», perhaps, but neither Korner nor Mayall were big fans of pure

rock’n’roll: they liked old-fashioned jazz, Delta and Chicago blues, a little

bit of soul (more Ray Charles than James Brown) — basically, any type of

music that one could be expected to sit down and listen to, rather than dance

one’s ass off (though a little bit of dancing every now and then couldn’t

hurt). And although both Korner and Mayall were more than sympathetic toward

those rough and rowdy kids — in fact, almost fatherly — it is almost as if

they found it somewhat undignified and unbefitting to try and challenge them

on their own terms: Alexis Korner never became Mick Jagger, and John Mayall

never became Eric Clapton or Peter Green. Ironically, it was not until the rough and rowdy

kids became stars that their «fathers» actually got themselves some record

contracts. Well, okay, so Korner (being the eldest one, after all) did begin

releasing albums as early as 1962, but Mayall had to spend eight years to

land himself a recording contract (although I’m not sure he actually bothered

— it’s more likely that the record industry eventually found him than his

ever being in a hurry to find the record industry). Whatever be the case,

Mayall’s first single with the Bluesbreakers was released in May 1964 and

consisted of two original compositions, featuring Mr. Mayall himself on

vocals and organ, Bernie Watson on guitar, Martin Hart on drums, and a

19-year old youngling called John McVie on bass. Yes, that’s exactly right: boot

up ‘Crawling Up A Hill’

and what you hear are the first ever known bass notes to be played by the

future bass king of Fleetwood Mac. The song, whose original studio version is included

as a bonus track on some editions of the album, is actually a damn fine piece

of British rhythm’n’blues from 1964 — though its most outstanding feature are

probably the lyrics, which are both semi-autobiographical ("I’ll quit my

job without a shadow of doubt / To sing the blues that I know about") and also clearly influenced by the

likes of Chuck Berry’s ‘Too Much Monkey Business’ and ‘Johnny B. Goode’

("working for a rich man, staying just a poor man, never stop to wonder

why"). It might, in fact, be the first semi-autobiographical song in the

history of British rock music altogether — considering that most of the pop

and rhythm’n’blues bands at the time were generally content to either sing

about boy-girl themes or faithfully cover whatever words they could capture

from across the Atlantic. (Apparently, some of its impact still persisted

even forty years later, since the song was even revived by Katie Melua

for her debut album — being the Georgian-born girl she was, she could

certainly connect to the "so here I am in London town / a better scene

I’m gonna be around" bit in a meaningful way). The melodic aspects of the song are slightly more

problematic, and it is a problem — or, at least, a peculiarity, since many

people might not find this a problem at all — of just about every «original»

song in Mayall’s early repertoire. On one hand, it is indeed quite impressive

that, where so many of his contemporaries simply covered American material,

Mayall was so adamant — so early on — about writing and recording his own

songs: almost everything on the early singles as well as this LP is credited

to Mayall himself (a stupidly misguided Wikipedia article will try to tell

you that ‘When I’m Gone’ is the Smokey Robinson hit for Brenda Holloway and

Mary Wells, but do we really want to believe that John Mayall would cover a

Motown song in 1965? Not on your life!). But on the other hand, just about

each and every one of these songs is a «steal» — melodically based on

something from the blues, soul, and rock’n’roll repertoire and only adding a

few tiny twists and tweaks so as to avoid copyright issues, which places us

in the uneasy position of trying to delve deep into the man’s mind and guess

whether all of this was being done as a loving tribute or as a tricky strategy

to make just a little more money on other people’s achievements. I’d probably

guess it was a little bit of both. ‘Crawling Up A Hill’ at least fares relatively

nicely in this department, though you shall almost certainly recognize its

verse melody as a slightly sped-up and tonally transposed take on Ray

Charles’ ‘Hallelujah I Love Her So’ ("every morning ’bout half past

eight" = "every morning ’fore the sun comes up", etc.); but

with the unusual twin attack of harmonica and Mayall’s Vox Continental organ

from the opening bars of the song, this circumstance is barely noticeable and

forgivable — also, the descending "minute after minute, second after

second" bridge, introducing a completely different melodic pattern,

seems to be fairly original to me. But the B-side of the single, ‘Mr. James’,

is nothing but a generic lyrical rewrite of Elmore James’ ‘It Hurts Me Too’ —

and the fact that Mayall supposedly wrote this explicitly as a tribute to the

recently deceased blues hero ("oh dear Mr. James, oh tell me why you had

to go?") does not entirely justify the fact that he could have at least

co-credited "dear Mr. James" for the recording. From then on, listening to John Mayall essentially

becomes a game of «guess that melody» — and although my knowledge of

pre-British Invasion era blues and soul music is considerably larger today

than it used to be in my childhood era of musical starvation, I am still not

sure that I am able to pick up on everything. I am kinda proud, though, that even before taking a listen to

John’s second single, entitled ‘Crocodile Walk’ (yes, that’s ‘Crocodile Walk’, not ‘Crocodile Rock’, Elton John got nothing on this,

baby!), I was suspicious that it might have something in common with ‘See You

Later Alligator’ — and sure enough, for most of the duration of the verse it

is the exact same song! only slowed down rather than sped up this time, and

the last bars of the verse take us in a slightly different direction from

Bill Haley’s. Still got a good swaggy groove, though, and a pretty nifty

guitar solo to boot — somewhat reminding me of John Fogerty’s classic style

from several years later (think ‘Working Man’, etc.; the similarities in

specific licks are even more pronounced on the live version). And it

definitely has more of a blues feel to it than Bill Haley’s rockabilly ditty. That guitar solo was not played by Bernie Watson, though. The single was released in

early April of 1965, a few weeks after Mayall’s first LP, which was itself

(following an example already established by Alexis Korner’s Blues

Incorporated in 1962) recorded live on December 7, 1964 at a club called

«Klook’s Kleek» in the West Hampstead area of London which, not too

coincidentally, was located just a few klicks (sorry) away from Decca’s

recording studio (I guess this might have something to do with the phenomenal

— for 1964 — sound quality of the live recording). By that time, the lineup

of the Bluesbreakers had already undergone some important changes: Watson was

replaced by one Roger Dean (nothing whatsoever to do with the guy who painted

all those Yes album covers), and Martin Hart was replaced on drums by Hughie

Flint — thus almost completing the classic Bluesbreakers lineup, with the

sole exception of that clean-cut «Beano» fellow. (On the live album, they are

also joined by Nigel Stanger on saxophone, though I don’t think he was a

salaried member of the band). Although all the other three members of the

Bluesbreakers were younger than Mayall by around 8–10 years (a distance that

would become ever larger with the subsequent incarnations of the band), they

mesh together fairly well, and it could hardly be said that Mayall is

«holding back» his bandmates or anything — more likely, he just tended to

choose those who suited his own musical temperament: tight, professional,

energetic, but at the same time restrained and free from the «primal»

excesses of young rhythm’n’blues-ish whippersnappers. In particular, the

McVie / Flint rhythm section is thick, flexible, and always reliable; the

bass is quite prominent in the remastered CD version and will be met with

unquestionable love from all fans of Fleetwood Mac-era John McVie. Meanwhile, Roger Dean is pretty damn good with his

instrument — he certainly does not have Clapton’s classic guitar tones and

smooth technique, but on some of these tracks he already rocks harder and

heavier than any electric bluesman from Chicago: check out, for instance, the

solo on ‘I Need Your Love’, where he begins with a series of licks that

integrate the soulfulness of Otis Rush with the jerkiness of Chuck Berry,

then gradually builds up to a torrent of up-the-scale trills which, in the

pre-Clapton era, could almost be considered «virtuosic». In an era when the

idea of a blues guitar hero had yet to materialize in the UK, this had got to

count for something at least. This leaves us with Mayall himself, and Mayall is

Mayall — solidly middle-of-the-road about everything he does, from singing

(nice high-pitched voice, but with little range or versatility) to playing

(good organ technique, but not that much subtlety or invention) to blowing (technically,

he might have been one of the best harp practitioners in England at the time,

but I’d still take Mick Jagger for the ability to brew atmosphere over

Mayall’s hat-tipping to Little Walter). The only thing he is truly awful at is stage announcing which he,

like Korner, does in the same annoyingly «mock-academic» tone, not to mention

occasionally trying to come across as way more hip than he actually is

("this one is called ‘I Need Your Love’, and is dedicated to all the

fine young chicks that are out front" — uh, so exactly with how many of

these «fine young chicks» did you «sow your wild oats» after the show, Mr.

Mayall?). And then, of course, there’s that weird

«semi-songwriting» all over the place: ‘I Wanna Teach You Everything’ is

‘Sweet Home Chicago’ ("come on, come on, let’s go..."), ‘I Need

Your Love’ is something by Muddy Waters (not quite ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’, but

close enough), ‘What’s The Matter With You’ is ‘Green Onions’ with lyrics, ‘Doreen’

is John Lee Hooker’s ‘Louise’, and ‘Runaway’ is a variation on Memphis Slim’s

‘Steppin’ Out’, which would soon, of course, be recorded under its proper

title with Eric on the studio album. I also suspect that the organ riff of

‘Heartache’ was taken from Rosco Gordon’s ‘Just A Little Bit’ (= ‘Don’t Want

Much’ as performed by the Animals), though a review on RYM also rightfully

remarked that the song itself eerily predates Shocking Blue’s ‘Venus’ (which,

on the other hand, as we all know, was ripped off from ‘The Banjo Song’ by

The Big 3, so I’m really getting

lost in here). The one song on which Mayall really jumps up to the

sky in search of originality is ‘The Hoot Owl’, with lyrics about... a hoot

owl, supposedly because this is exactly what John was reminded of when

experimenting with the electronically tampered sound of the Cembalet electric

piano, which he occasionally plays on the album. Of course, the tune itself

is a joke song, something with the aesthetics (if not the actual sound) of

somebody like the Coasters, but at least it shows that Mayall’s creativity

occasionally amounted to something other than renaming ‘Louise’ into ‘Doreen’

or changing alligators for crocodiles. On the other hand, heck, everybody steals, as John subtly

points out to all of us by merging ‘Night Train’ and ‘Lucille’ quite

seamlessly into a single track — and this time, actually indicating the

original credits. Fuck it. Finally, the closing number, ‘Chicago Line’, raises

the excitement up a notch, with its noisy and aggressive enhancement of the

Bo Diddley beat that puts it somewhere in between Bo Diddley proper and

future Who-style jamming on ‘Magic Bus’, with the added pleasure of a

«dialog» between Dean’s guitar and Mayall’s harp and Cembalet, suspenseful

and funny at times: definitely an above-average finish to an overall

intriguing, if not always exciting, experience. On the whole, it’s just a damn good record, the

quintessential spectacularly unspectacular album from a hard-working

non-genius with excellent taste and solid craft. Sound-wise, it blows any live album of UK rhythm’n’blues preceding

it — Blues Incorporated, Alex Harvey, even Five Live Yardbirds — out of the water. John McVie and Roger Dean

provide almost-first-rate bottom and top layers. And, in some ways, I’m glad

that Mayall «mutated» all those songs, because he managed to keep me more

entertained that way, on my «now where have I heard that one before?» toes from start to finish. If it were all just

John Lee Hooker and Booker T covers, this review would have been much

shorter, that one’s for sure. |

||||||||

![]()