|

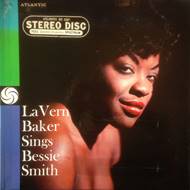

Of the two homages to the Empress of the Blues, LaVern’s

— upon first hearing, at least — should be unquestionably declared the big

winner. Dinah Washington was an elegant, polite, well-mannered jazz lounge

performer, a master of exquisite phrasing and manneristic sentimentality;

LaVern Baker was a rough, gruff, loud-mouthed soul sister who looked like she

could easily punch your lights out at the first opportunity. When the idea to

record a set of Bessie Smith songs was pitched to her, she allegedly agreed

only if she were allowed to do it «her way», which, naturally, was the best

way to do it, because «her way» of doing things, from the very start, had a

lot of obvious similarities with Bessie’s way: loud, powerful,

uncompromising, feministic, dominant. And she could have that aggressive

bark’n’roar in her voice which was lacking even in the wildest performances

of her direct predecessor and strongest competitor at Atlantic (Ruth Brown).

If ever there was one performer at the time to give these gritty old tunes a

coloring of Fifties-style sassiness and grittiness, it’d be Miss Baker.

(Sister Rosetta Tharpe might be a good candidate, too, but she’d probably

refuse to sing such Godless smut).

For the recording, Baker was given a full-on jazz

backing band rather than Atlantic’s standard R&B session players; I do

not easily recognize any of the names, but this is simply because I am not a

well-versed jazz connoisseur — those who dig deep enough into classic

recordings to diligently study the liner notes will most certainly be

familiar with Buck Clayton on trumpet, Jimmy Cleveland on trombone, Wendell

Marshall on bass, and others (also, note the legendary Tom Dowd on

engineering duty, although he’d already been a regular on Atlantic records

for a couple of years at least). Predictably, the arrangements are tight,

thick, meaty, imposing, celebratory... and not particularly memorable, though

I guess the same could be said about the original, much more lean-and-mean,

Bessie Smith recordings (unless she paired up with somebody truly

outstanding, such as Louis Armstrong).

Less predictable is LaVern’s song selection: she

seems to consciously avoid most of Bessie’s «broken-hearted and lonely»

ballads (other than ‘After You’ve Gone’) and concentrate more on her

affirmative sides — the reckless fun of ‘Gimme A Pigfoot’, the religious

ecstasy of ‘On Revival Day’, the fight-for-your-right attitude of ‘I Ain’t

Gonna Play No Second Fiddle’, and basically anything that, no matter how grim

or desperate, ends with an "as God is my witness, I’ll never be hungry

again" attitude (‘Nobody Knows You When You’re Down And Out’, etc.).

Consequently, this is not a complete portrait of Bessie Smith — she had her

share of lay-me-down-and-die songs, too — but a legitimate one, since such,

indeed, was the stereotypical image of Bessie transmitted to us from her

times.

Still, despite the updated and expanded

arrangements, despite the interesting track selection, despite Baker’s vocal

powers that are beyond questioning — I cannot help but ultimately find the

record a bit dull. Amazingly, I find it easier to make my way through an

entire 70-minute CD of Bessie’s own recordings, poor sound quality and

everything, than to patiently make it to the end of this 42-minute long

experience. There is a nagging feeling that once you’ve enjoyed the opening

song, ‘Gimme A Pigfoot’, you’ve pretty much heard it all — a feeling that is

not quite as pervasive when you listen to the originals. Of course, part of

the reason is technical: Bessie’s blues tunes, even if they are usually not

far from each other melodically, were recorded over a period of about ten

years, with lots of different players and Bessie herself passing through

different stages — as opposed to this record, made up quickly with the exact

same band and featuring the exact same arrangement style, so even if the

arrangements are richer, they can still feel more monotonous. But

unfortunately, that’s not all.

There is, after all, a reason why Bessie Smith is a major legend and LaVern Baker is a minor legend, and it is good to have

this tribute album to help us get to the bottom of it, instead of wasting

time on useless debates about whether ‘Soul On Fire’ and ‘Tweedlee Dee’ are

more powerful than ‘Back Water Blues’ and ‘On Revival Day’. LaVern gets it

absolutely right when she sees Bessie Smith as a proverbially strong,

imposing character — and she does her best to match Bessie’s strength and

monumentality with her own. But that is pretty much the only aspect of Bessie that she sees, or, at least, is able to

extract and adapt to her own personality. The result is that every single

song on here feels like an onslaught: with the very first song, LaVern boxes

you into a corner and then just keeps punching and punching and punching.

It’s deliciously brutal at first, but then you kind of just get used to it,

go a bit numb, and start taking the punches like Rocky from Apollo Creed. At

the end of it all, you got a good beating, but that’s pretty much all you

got.

At the same time, what goes almost completely

untransferred is the sensitive — sensitive,

not sentimental — side of Bessie

Smith. At her best, the Empress of the Blues can bring me to tears, even

through all the crackling and distortion of her voice, because she had the

uncanny talent of sounding powerful and

vulnerable at the same time: strong and determined, yes, but just as well in

need of comfort, mercy, and pity. This part of her personality is all but

missing in LaVern’s versions; ironically, it might make more sense to hunt

for it in the interpretations of Dinah Washington — it’s as if the two ladies

split the complex character of Bessie Smith in half and each ended up with

but one side of it (though, admittedly, LaVern got the bigger and better

part). From a rigidly progressive point of view, you could fully justify this

— for instance, describing the sensitive and vulnerable qualities of Bessie’s

singing as elements of patriarchal submission, rightfully cleansed out by

LaVern’s aggressive stance — but I’d rather cleanse out the rigidity of the

(pseudo-)progressive point of view instead.

None of this serious criticism should, of course,

undermine the importance of this record for LaVern’s own legend: at the very

least, having it sit alongside her seemingly novelty pop hits such as

‘Tweedlee Dee’ and ‘Jim Dandy’ raises the stakes for those very songs

themselves, much as we can feel more respect for ‘Yellow Submarine’ and ‘All

Together Now’ knowing that they came from the very same minds that created

‘Eleanor Rigby’ and ‘Hey Jude’ — or, to use a chronologically and

stylistically closer analogy, this is somewhat akin to the jazz albums of Ray

Charles, which are never going to occupy the same pedestal as records by

proper jazz greats, but help provide a solid musical context for Ray’s

comparatively «light weight» three-minute R&B hits for his label. It is

all the more impressive considering that not a lot of Atlantic artists were

allowed — much less stimulated — to have such parallel «serious» careers

alongside their blatantly commercial projects; Ruth Brown, for instance, was

never offered to make any such conceptual records.

So, ultimately, there is quite a lot going for LaVern Sings Bessie Smith — or, at

the very least, it is one of those forgotten records which easily lends

itself to digging out and finding all kinds of historical and sociological

importance (just see how much I have already written, without even discussing

most of the music). Yet even if you develop a true taste for all things

Fifties-related, it is hard for me to imagine anybody being more attracted to

this kind of stuff than to the guilty pleasures of ‘Jim Dandy’ — or even ‘Jim

Dandy Got Married’, for that matter.

|

![]()