|

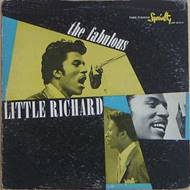

In any case, God may have possessed Little Richard,

but it was Specialty Records who possessed the rights to Little Richard’s

recorded output, and as long as rock’n’roll was not dead (and in 1958, it was

still hanging on), the option to just sit on it was a non-option. The best

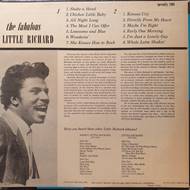

stuff always gets rolled out first, and for this 12-song collection, the

label diligently put together most of the A- and B-sides they had released up

until July 1958, not forgetting even the three singles which had not

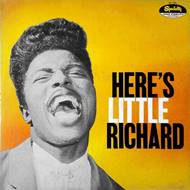

originally been included on Here’s

Little Richard, though they could have: ‘Heeby Jeebies’ (October ’56),

‘The Girl Can’t Help It’ (December ’56), and ‘Lucille’ (February ’57). These

were later followed by ‘Keep A-Knockin’ (August ’57), ‘Good Golly Miss Molly’

(January ’58, though recorded as early as October ’56), and ‘Ooh! My Soul’

(May ’58).

These are, almost naturally so, the best songs on

the entire album; my only problem with them is that I do not really have any

illustrious insights to explain what makes them delightfully different from

‘Tutti Frutti’ and ‘Ready Teddy’. Well, except for ‘Lucille’, perhaps.

‘Lucille’ is different — of all of Little Richard’s early singles, it is the

most musically intriguing, since its major hook comes neither from the vocals

nor from the lead instruments, but from Frank Fields’ iconic train-style

bassline. This makes the song feel unusually deep and heavy for Richard —

hardly a coincidence that Deep Purple loved to cover it on stage — yet at the

same time, it has a flying feel, due to the bassline’s steady

rising-and-falling pattern. In contrast with the wild and noisy sound of most

of the other hits, ‘Lucille’ feels sharp, collected, almost a little mystical,

all because of that bass power. (Do not laugh, but I think that my very first

childhood acquaintance with the song was through Paul McCartney’s 1988 cover

on his Back In The USSR album —

and even in that Eighties-colored context, it managed to sound distinctly

different and more threatening than any other song on that record). There’s

also the deal with its bridge section, whose "I woke up this morning,

Lucille was not in sight..." does

sound like a distant, yet personalized, threat, as if the wildman whose

wildness used to be fairly abstract suddenly began to focus his attention on

somebody in particular. All in all, this goes farther than innocent party

fun.

The others really don’t. ‘Good Golly Miss Molly’

also calls a girl by name, but merely to express admiration at her crazy

dancing skills, and there is no creepy bassline to spoil the atmosphere,

either. Lyrically, it is more innocent than ‘Long Tall Sally’, though, of

course, not being able to "hear your momma call" does bring on

certain implications anyway. Just how many Miss Mollies were seduced by these

devilish howls into selling their souls (and their parents) for rock’n’roll

remains statistically unclear, but I’d bet anything that their number by far

exceeded the number of souls Father Pennyman was trying to bring closer to

the Lord at the very same time his latest single hit the stores.

‘The Girl Can’t Help It’, a song that ended up as a

lustful ode to the allure of Jayne Mansfield in the famous rock’n’roll movie

of the same name, slows down the tempo just enough for us to be able to make

out each single word — "if she smiling, beefsteak they come well

done" (how the hell did this ever make its way past censorship?). And

the old joke tune ‘Keep A-Knockin’, which Richard re-credited to himself on

the formal basis of new and improved lyrics, put Louis Jordan to sleep

forever, as it whipped up Richard’s already classic frenzy to even higher

levels — this is rock’n’roll madness incarnate right from the opening

«knocking» drum fills, which even John Bonham saw fit to eventually

incorporate into Led Zeppelin’s ‘Rock’n’Roll’ — as if saying, «You say rock’n’roll, you think keep a-knockin’ but you can’t come in».

That said, already here a few of the entries are

marginally less hot than classic competition. For some reason, every once in

a while Little Richard chose — or was forced to choose? — to perform old show

standards, such as ‘Baby Face’ and ‘By The Light Of The Silvery Moon’; one

theory says that this was the record company’s evil plan to make peace

between the terrifying rock’n’roller and the terrified parents of his fans,

while another theory says that this was essentially a joke on Richard’s part,

since the numbers would be recast in his wild rock’n’roll mood anyway. There

is no denying that he does a solid singing job on both tunes, but they do

come across as comical rather than exciting, especially if you are familiar

with the source material — and, therefore, cannot really hold a candle to the

«genuine» stuff.

There are also a couple strangely softer numbers,

such as ‘All Around The World’, written by the trusty Robert Blackwell but cast

in a poppier style, with kid-friendly sax riffs and a rather bland approach

to belting out those blues triplets. ‘I’ll Never Let You Go (Boo Hoo Hoo

Hoo)’ is also a bit of a throwback to Little Richard’s earliest days of

R&B singing, though still worth experiencing just to hear the unique

vocal register juggling over all the "boo-A-hoo-A-hoo-A-hoo"s. For

the record, this is also where you will find ‘Hey Hey Hey Hey’, which, I

think, most people believe always comes bundled with ‘Kansas City’ after the

Beatles did the bundling, but in reality they are quite different entities —

‘Hey Hey Hey Hey’ begins with "going back to Birmingham, way down in

Alabama", which the Fab Four might have found a tad too... localized to sing about (or perhaps

they did not want any unnecessary political connotations, given the situation

in 1963–64).

Anyway, the simple truth is that fast Little Richard

is almost always preferable to slow Little Richard, and not the least

because, somehow, all the fast songs on this album sound different, while

most of the slow ones sound exactly like ‘Miss Ann’ and ‘Oh Why?’ from the

previous record. But then again, there was a good reason why most of the slow

songs were B-sides and most of the fast ones were A-sides — and, fortunately

for us and for Specialty Records, Little

Richard puts together enough of the latter to still produce a terrific,

awe-inspiring impression.

|

![]()