|

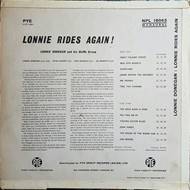

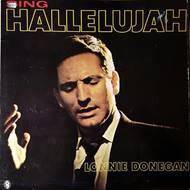

However, before vanishing

into obscurity, Lonnie managed to leave behind what was arguably his most

ambitious project: a full-fledged gospel album. Prior to that, he’d taken on

the gospel spirit every once in a while (‘Light From The Lighthouse’, etc.),

but this time his selection of cherished folk standards is strictly

conceptual. Of course, this has nothing to do with the fact that Mr. Donegan

had suddenly found the Lord (he might have, I have no idea, actually), but

rather with the fact that he wanted to make good use of the LP medium: with

the idea that LPs should not be collections of singles but rather artistic

entities in their own right seemingly more popular in the UK than in the US

at the time, it is no wonder that Sing Hallelujah does not reproduce

any of Lonnie’s 45" records, but instead paints a wholesome picture of

the artist as a God-fearin’ and a God-lovin’ man. It is much more of a

wonder, though, that it does so quite convincingly and, in places, even admirably well.

Of course, there is no

huge difference between this album and Lonnie’s typical skiffle output. This

is not «gospel» in the solemn Mahalia Jackson sense of the word: this is

largely folk-gospel, with the main difference being the religious rather than

secular nature of the lyrics. On some of the tracks, Lonnie and his backing

band are fortified by some extra choir singers, but that’s about it —

otherwise, we have just the same folk-blues and country-blues melodies, and

the same vocal style which hasn’t evolved all that much since 1956. But

neither has it deteriorated or lost its charisma; Lonnie’s thin, frail, but

highly flexible and, at times, surprisingly determined tenor voice, when it

enters religious mode, can often bring forth the same kind of vibe that you

get from, for instance, George Harrison’s solo records — a sense of

«conviction through weakness», the faint intuitive understanding that you are

witnessing a frail and insecure human being attempting something overtly

courageous, taking a crazy risk which can pay off only if you manage to put

all of your heart in it.

It all begins already on

the title song, where Donegan sets himself the mission of impersonating a

zealous preacher, capable of lighting the Lord’s fire in his listeners’

hearts — a pompous track, punctuated by deep bass, almost jungle-level drums,

and swampy electric guitar licks, while Lonnie himself skilfully relies on

the quiet-to-loud vocal dynamics to mark that exact «jump of courage» I’m

talking about. It might not be true fire-and-brimstone level, but I find the

effect believable and inspiring, and definitely going beyond the level of

«cute little Scotsman impersonating a deep Southern preacher man for the local

sailors’ amusement»; in fact, I might have felt even more respect for the

track had I never known the artist behind it in the first place.

A lot of the other tracks

are less overtly spiritual in atmosphere, closer to the slight-and-joyful

merry-go-rounds for which Lonnie was already well known — ‘No Hiding Place’,

‘Chariots A’-Comin’, ‘This Train’, etc. — but Lonnie is at his best here on

the more quiet, intimate tracks, such as ‘His Eye Is On The Sparrow’, which

he performs in the tender, sentimental style of the Everly Brothers, and

‘Steal Away’, which gets an arrangement not unlike a romantic Elvis ballad

from one of his soundtracks, and features one of Donegan’s most exquisite

vocal performances.

But the best is saved for

last, because Lonnie’s rendition of ‘Nobody Knows The Trouble I’ve Seen’ may

easily be the best of all the versions

of this tune that exist — and I have heard quite a few, but most of them were

either too happy (Louis Armstrong), too overdramatized (Mahalia Jackson), too

poppified (Sam Cooke), or too restrained by instrumental and vocal

conventions of the respective age (Marian Anderson’s performance from 1924 is

outstanding, but much too academic-operatic, if you get my drift). Lonnie

takes it as a torch ballad of sorts and uses each square inch of his vocal

powers to do precisely what the song requires to do — convey a full spectrum

of emotions from utter depression and desperation to undefeatable optimism

and hope for a light in the darkness. The man clearly gets it, and is able to

make you get it. This is not

imitation; it is a deeply personal interpretation of a hymn which may be

relevant for us all, Christian or not, beautifully performed in the

quintessential humanistic spirit. It is much too sad that, even in the hearts

of those few aging fans who still remember Lonnie with nostalgia, he will

probably be forever present with that ‘Chewing Gum’ song rather than this absolutely phenomenal

performance.

Ultimately, if you ever

find yourself doing an inquisitive sweep-up of neglected pre-Beatles music,

do not forget about this record. It gets a pitifully low rating on

RateYourMusic, probably from people who did not even listen to it in the

first place but simply dismissed it because, come on, skiffle clown Lonnie

Donegan singing gospel? what a joke, right? Wrong: as Shakespeare already

would have us know, clowns are often more intelligent, sensitive, and humane

than Serious Artists, and I personally would take Lonnie’s idea of a gospel

album over ninety percent of gospel artists I have heard. Because it is one

thing to inspire respect and reverence, and quite another thing to actually

endear yourself to the listener by performing century-old museum pieces like

these.

|

![]()