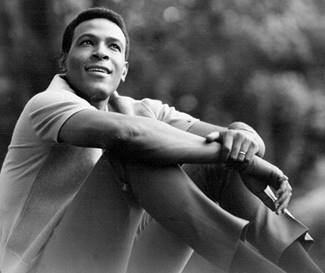

MARVIN GAYE

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1961–1984 |

Classic soul-pop |

Page

contents:

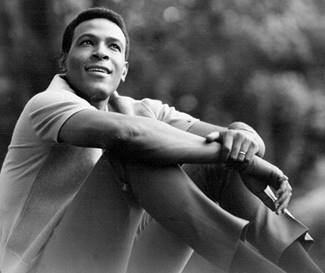

MARVIN GAYE

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1961–1984 |

Classic soul-pop |

Page

contents:

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Album

released: June 1961 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

2 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) (I’m Afraid) The Masquerade Is

Over; 2) My Funny Valentine; 3) Witchcraft; 4) Easy Living; 5) How Deep Is

The Ocean (How High Is The Sky); 6) Love For Sale; 7) Always; 8) How High The

Moon; 9) Let Your Conscience Be Your Guide; 10) Never Let You Go (Sha-Lu Bop);

11) You Don’t Know What Love Is. |

||||||||

|

REVIEW Marvin Gaye liked Berry Gordy, and

Berry Gordy liked Marvin Gaye. That was enough to get Marvin Gaye signed to

Motown Records as a solo artist, even if there was precious little evidence

of his good prospects at the time; he’d done a little singing in a vocal

quartet, a bit of backing for other artists (funny trivia bit — that’s Marvin

Gaye out there, with several other dudes, singing backup vocals on Chuck

Berry’s ‘Back In The USA’ and ‘Almost Grown’), and a little drumming as a

session player on other people’s records. Yet all it took was one fateful

meeting with Gordy at his house in December 1960 — a meeting without which we

might never have had ourselves a What’s

Going On, because, for all his notorious artistic stubbornness and

tenaciousness, throughout his life Marvin also needed quite a bit of

guidance; and for the first decade of his career, he owned quite a huge debt

both to Berry and Anna Gordy (Berry’s elder sister, whom he married and who

was quite a motherly figure to him for a while). It’s not even entirely clear

what Berry saw in Marvin back at that meeting, other than his charming

youthful looks, but who of us wouldn’t have envied tha kind of intuition? |

||||||||

|

The greatest

irony of Marvin’s first year at Motown, though, is that his and Gordy’s story

pretty much inverts the classic stereotypical narrative of «struggling

independent artist asserting his identity in the face of the greedy and

calculating record executive». Gordy, who had only just begun building up the

image of his company as the flagman of a brand new pop sound, commercially

viable and artistically relevant at the same time, wanted Marvin to become a

living brand for that direction. Marvin was really uncomfortable with the

idea, though — not so much because he despised that kind of lowbrow

teen-oriented entertainment, but largely because it required a kind of stage

presence for which he was not ready. Instead, it was he who insisted upon pursuing a more «adult» route, singing dusty

old standards «for grown-ups» in the good old fashion of a Nat King Cole,

albeit slightly modernized for a new decade. In other words, the record

executive wanted the artist to be hip, modern, and progressive; the artist

insisted that the record executive let him be square, old-fashioned, and

out-of-time. And, in what would be the first, but far from the last time, the

«stubborn kind of fellow» had the upper hand over the record executive — much

to his own chagrin, in the long run. Actually, the

run wasn’t even all that long: Marvin’s first complete LP for Motown hardly managed

to catch anybody’s serious attention. First, it clearly wasn’t the right

place: throughout 1959–60, people had already grown accustomed to Tamla /

Motown’s initial roster of artists — The Miracles, Barrett Strong, Mary

Wells, Eddie Holland — and none of them were exactly doing the play-it-again-Sam routine, so an

entire album culled from the Songbook for Motown would be like Ivo

Watts-Russell signing Michael Jackson to 4AD a couple of decades later.

Second, it clearly wasn’t the right time: the procedure was such that you’d

need to become a relevant contemporary hitmaker first, and then start pleasing Grandpa and Grandma later — see both Ray Charles and Sam

Cooke, two of Marvin’s primary inspirations. Third, well... the album just

isn’t very good, you know. Simple as that. One general issue

with Marvin Gaye is that — and I do realize it’s a pretty subjective assessment

— while his singing has always been perfectly professional and strongly

charismatic, his voice is hardly what I’d call «outstanding»: it does not

have its own, unique, immediately recognizable timbre, and his phrasing is

devoid of any individualistic trademarks that, with some other singers, could

allow even a mediocre song strongly register across your conscience. In other

words, for a Marvin Gaye recording to count as great, it needs to have a

strong musical backbone behind the nice voice — which means that he really

should have avoided approaching the Songbook within a ten-mile radius. For

all the flack I’ve thrown at the likes of Sam Cooke for doing this thing, Sam’s

timbre, range, and modulation are precious gifts in themselves; next to him, Marvin

has a softer, weaker voice, and he hardly ever tries to generate any intrigue

with it. The

arrangements are fairly tasteful, more in the vein of late night jazz than orchestrated

Hollywood pap; Marvin’s own piano playing (and, occasionally, drumming) are

at the center of things, with light jazzy electric guitar coming in next (the

credits do not list the actual players, but there’s some pretty damn nice and

fluent soloing on ‘Always’ and a couple other tracks), and the swingin’

groove can get surprisingly tight and jumpy for a record label that is least likely to be associated with

this kind of genre. But taste is not enough — you have to prop it up with

either dazzling virtuosity, which would be too much to require of Motown’s home

band, or unique arranging vision, which Berry Gordy was unable to provide. The

result is predictable: The Soulful Moods

Of Marvin Gaye is pleasant background muzak that goes against core Motown

values and barely offers any glimpses into the glorious future that would

eventually await Marvin on the label. Arguably the

only point of mild interest here is Marvin’s very first single for the label,

thematically and stylistically different from the bulk of the LP but probably

included to fill up space or simply to give it another chance. ‘Let Your Conscience

Be Your Guide’ is a slow, sentimental blues waltz with a pervading organ

melody (to give it a bit of a Ray Charles feel, I guess); although written by

Gordy specially for Marvin, it still feels more somber and serious than the

usual early Motown stuff like ‘Money’ or ‘Shop Around’ — and far more

old-fashioned than required from the times. The B-side, ‘Never Let You Go (Sha-Lu

Bop)’, is actually more interesting: co-written by Marvin’s old manager Harvey

Fuqua and Anna Gordy herself, it is a tricky dance number, combining two

different time signatures, a heavily syncopated one in the verse and a

straight Little Richard-esque boogie-woogie in the chorus — although, at this

point, Marvin’s natural shyness and restraint still prevent him from fully

exploiting the song’s potential of excitement. In the end, we

are left with mostly historical interest: The Soulful Moods was not just Marvin’s first album, but the very

first LP released on the Motown label (along with Hi We’re The Miracles, which allegedly followed it in about a

week’s time) — and, stylistically, also one of the most unusual LPs to be

expected from the Motown label. Knowing that it exists will help you get a

better understanding of Gaye’s complex personality — but keeping it around

probably won’t help get you a better appreciation of Gaye as a masterful

interpreter of the Songbook. |

||||||||

![]()