|

You’d be dead wrong, though. Just

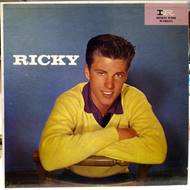

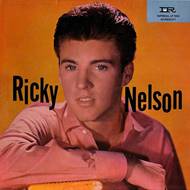

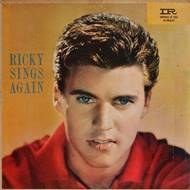

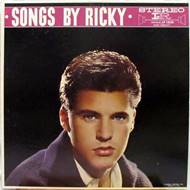

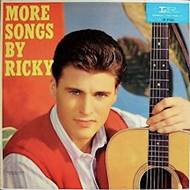

as there is hardly any difference between Ricky’s, uh, sorry, Rick’s good looks on the front cover

and all his previous photos, so is there hardly any musical sign on here that

the boy is no longer a boy, but a man, spelled M-A-N, no B-O-Y child. «Wait a

minute», you’ll say, «but there’s ‘Travelin’ Man’ on here! Surely a song like

‘Travelin’ Man’ is all toxic macho testosterone material, the kind of tune

he’d be too shy to sing even a couple of years earlier?» Indeed, these days,

in our age of heightened sensitivity, no positive account of ‘Travelin’ Man’

that you encounter anywhere in cyberspace can pass without at least a little

bit of apology for the «cringey» lyrics. Yet

there are nuances.

‘Travelin’

Man’, written by the as yet largely unknown Texan songwriter Jerry Fuller,

was originally offered to Sam Cooke — and, for some reason, downvoted, even

though I can easily imagine Sam singing

the song, which would have fit neatly into the concept of some of his

glitzier albums like Cooke’s Tour.

Instead, it was passed down to Ricky, almost by accident, and although he

allegedly loved Fuller’s demo, I can hardly believe that he didn’t have a bit

of a hard time putting himself into the shoes of a jaded polyamorous sailor

who has, in every port, owned the heart of at least (at

least!!!) one lovely girl.

Actually, I don’t know what I’m talking about, because Ricky Nelson does not

really put himself into the shoes of anyone: he is, and has always been,

Ricky Nelson.

And that, by the way, is the saving grace

of ‘Travelin’ Man’ as performed by Ricky Nelson. Yes, Fuller’s lyrics are

tacky — not so much for the concept, really, which is in itself a time-honored

sailor’s trope, but rather for the sheer amount of tired «exotic

clichés» (‘pretty Señorita waiting for me’, ‘my sweet

Fraulein’, ‘my China doll’, etc.) that would make Tin Pan Alley stalwarts

like Cole Porter throw up in disgust at the rapid decline of poetic craft in

popular music. And if the song were sung by, say, the likes of Tom Jones, or

even Elvis — «real men» with lotsa

hair on their chests and everything — that tackiness would be multiplied to

scary dimensions. Nelson, however, delivers the words in his usual style:

soft, tender, melancholic, and without a shred of annoying braggadocio. In

his performance, the protagonist is no modern day Casanova — this here is

more of an ‘Everybody’s Trying To Be My Baby’ vibe, except that the Perkins

song portrayed a flamboyant rock star, besieged by obsessed girl admirers:

the Nelson-sung ‘Travelin’ Man’ would have ladies all over the world flinging

themselves at «travelin’ man Ricky» for his shyness, politeness, and

courteousness instead. None of that is in the lyrics, of course; it is all in

the voice, which oozes respect and admiration for every one of his

«conquests».

What

really makes the song into a mini-pop masterpiece, though, and is quite

likely responsible for a good number of additional sales, is its musical

arrangement — and, above everything else, that mesmerizing bassline played by

Joe Osborn (who, by the way, was the one to bring the song to Ricky’s

attention). The little rise-and-fall, fall-and-rise melody here is roughly

the same as on Arthur Alexander’s ‘Anna (Go With Him)’, which we usually know

from the Beatles’ Please Please Me

cover, evoking a world-weary feel from someone who’s accepted that life shall

never again be the way it was meant to be in one’s naïve, idealistic

past — and thus, the bass foundation helps reinforce the tragic feeling of all those ladies waiting for Ricky back in

Mexico and Hong Kong, a tragedy both for them and the protagonist, whose fatal wanderlust prevents him from

ever settling down with one of them. Thus it is a thematic prequel for the

Allmans’ "when it’s time for

leavin’, I hope you’ll understand that I was born a ramblin’ man",

but in between Dickey and Ricky, Dickey is the one here who sounds more like

a dick (duh), and Ricky the one who sounds like... well, like somebody whom

I’d be more likely willing to want to «understand» rather than simply condemn

off the bat.

A funny,

but sharp assessment of the ‘Travelin’ Man’ / ‘Hello Mary Lou’ single on

RateYourMusic notes that the B-side is "I’m not one that gets

around", while the A-side is "Sex tourist anthem". Ironically,

though, it is the fast tempo and slightly comical country jerkiness of ‘Hello

Mary Lou’ that make it feel more

like an improvised passion fling on the part of the protagonist, while ‘Travelin’

Man’ actually ends up feeling more sincere and «gentlemanly» in spirit. The

bottomline here is that ‘Hello Mary Lou’ is just a feel-good piece of

country-pop: the

original version by Johnny Duncan, released less than a year prior to

Ricky’s, or later versions (for instance, the CCR cover on Mardi Gras), though formally

different in terms of arrangements, all share more or less the same merry

spirit, and you can’t do much of anything about it. Rick’s performance is

okay, I guess, but he tries to invoke the feeling of ecstasy, and it comes

nowhere near as naturally to him as the feeling of world-weariness and

melancholy.

Even a

quick check on the SecondHandSongs resource shows that there have been more

than 150 different covers of ‘Hello Mary Lou’, including some pretty big

names — yet less than 50 for ‘Travelin’ Man’, mostly by various obscure (at

least for non-country fans like myself) country artists. Perhaps it was the

lyrics that drove people away, but in the end it is no simple coincidence

that ‘Travelin’ Man’ seems as if it could only

work if sung by the likes of Nelson (maybe Nick Drake or Elliott Smith could

have given it a go?), while ‘Hello Mary Lou’ could have been belted out by anybody

from Robert Plant to Freddie Mercury, had they ever wanted to. Actually, both

of them did.

It’s a

little odd, though, that two of Ricky’s best-remembered hits ended up on two

sides of the same single, in light of the fact that the chronologically adjacent

singles on both sides aren’t too hot. ‘You Are The Only One’, from the hands

of the trustworthy Baker Knight, was released in November 1960 and only made

it to #25 — a rather tepid rhythmic ballad exploiting Ricky’s «paranoid

lover» image (the hookline throughout is what’ll

I do if you leave me?, to which all of us insecure men desperately

needing their partners as anchors can relate), but without any strong musical

ideas to back it up. Curiously, the B-side was a cover of Elvis’ rendition of

‘Milk Cow Blues’ — I don’t know why, maybe James Burton wanted to play some

tough rock’n’roll for a change, but this is not Nelson-ready material,

really.

Then,

several months after ‘Travelin’ Man’, the Nelson team decided to make

lightning strike twice and commissionned yet another «travelog» from Jerry

Fuller — ‘A Wonder Like You’. With the momentum still going strong, the

record shot up the charts but still ended up stalling at #11 — and, once

again, I can hardly blame the instincts of the people. Formally, it seems to

follow the same formula: a similar tempo, the exact same tinkling piano

rolls, and lyrics that exploit the same subject yet are far more wholesome

and family-friendly. This time, our hero is no longer falling for the charms

of all the places he is visiting or

all the different types of girls he is encountering: "I’ve seen the pretty dancing girls of Siam

/ The happy Polynesian people, too / But they’re not as happy as I am /

’Cause they haven’t got a wonder like you" (and note the beauty of

the rhyming — "Siam" and "as I am"! Finally, Cole Porter

would be proud).

The

problem is, ‘A Wonder Like You’ is a bland, diet version of ‘Travelin’ Man’.

Do spare a few minutes of your time and play them back to back, just to

imprint in your mind the difference between «musical depth» and «musical

shallowness». The follow-up single is a bundle of simplistic sentimentality,

delivering its trivial message with no subtext whatsoever; ‘Travelin’ Man’,

in comparison, feels like a Shakesperian tragedy. Even if you dislike the

song, you cannot deny that it lends itself to all sorts of different

interpretations, and that your feelings for its protagonist can range from

sympathy and devotion to pity and hatred, depending on where your mind takes

you. The protagonist — and the emotional content of — ‘A Wonder Like You’ —

is just a puddle of warm milk. Even the B-side, ‘Everlovin’, a Buddy

Holly-esque pop rocker originally recorded by The Crescents, an Australian

vocal trio that supported Ricky on his tour of the continent, is preferable,

due to the lack of any artificial sentimentality.

Neither of

these two singles made it onto Ricky

21 (well, ‘A Wonder Like You’ was recorded already after the album), but

both ‘Travelin’ Man’ and ‘Hello Mary Lou’ did, and, naturally, they overshadow

most of the other selections — even if the team did manage to get both Jerry

Fuller, the author of the former, and Gene Pitney, of the latter, to

contribute several other numbers to complete the LP. Of Fuller’s two

additional numbers, ‘Break My Chain’ is the faster, more energetic and more

memorable one, but what strikes me most about the song is that Bob Dylan

actually took it as the basis for his own ‘On A Night Like This’ fourteen

years later — although the general pop structure of the verse doesn’t look

terribly original, for some reason, it is the Dylan song that springs to my

mind most immediately. ‘That Warm Summer Night’ is a rather non-descript

romantic ballad, though it still has more soul to it than ‘A Wonder Like

You’. Meanwhile, Pitney’s ‘Sure Fire Bet’ is ‘Hello Mary Lou’ all over again,

only with a little less verve. The future of these little pop ditties often

depends on the subtlest detail. "Hello

Mary Lou, goodbye heart" delivered the goods; "you’re a sure fire bet to win my lips" sorta didn’t.

The other

lightweight pop-rock contributions made by big names such as Dorsey Burnette

(‘My One Desire’), Johnny Rivers (‘I’ll Make Believe’) and Dave Burgess

(‘Everybody But Me’) are all nice, but, well, lightweight — nothing in

particular tickles the ear in any unusual manner. To round out the record,

Ricky falls back on old standards: ‘Do You Know What It Means To Miss New

Orleans’ is a waste of time because I’m not at all sure that Ricky really knows what it means to miss New

Orleans, but for ‘Stars Fell On Alabama’, he is somehow able to put on his

‘Lonesome Town’ «cloak of intangibility» and remind us all once again of that

mystical aura of icy emotion he could so effortlessly exude on his earliest

recordings. I’m not a fan of this style at all, but I’m pretty sure ‘Alabama’

is his best vocal performance here after ‘Travelin’ Man’.

Even so,

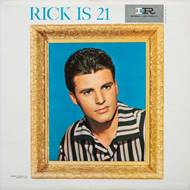

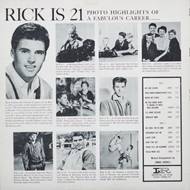

there is no question that Rick Is 21

is only going to live on in history as a repository for the biggest single of

Nelson’s entire career. Perhaps therein

lies the symbolism — look at how the world is ready to greet an adult Rick

Nelson with open arms, sending him back to the top of the charts and

everything. If so, the irony is cruel in retrospect, seeing as how the poor

guy only had, at best, a couple years of limited fame and fortune in front of

him before the British Invasion and new musical standards would forever brand

him as a has-been teen idol... but let us not jump too far ahead: for now, we

are still in 1961, and as of now, Rick Nelson, Travelin’ Man Number One, is

on top of the world.

|

![]()