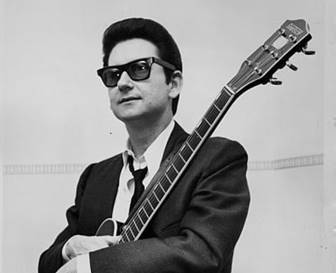

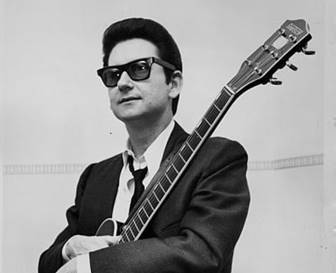

ROY ORBISON

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1956–1988 |

Pop rock |

Crying (1961) |

Page

contents:

- Sings

Lonely And Blue (1961)

- At

The Rock House (1961)

- Crying

(1962)

ROY ORBISON

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1956–1988 |

Pop rock |

Crying (1961) |

Page

contents:

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Album

released: January 1961 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

2 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

5 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) Only

The Lonely (Know The Way I Feel); 2) Bye-Bye Love; 3) Cry; 4) Blue Avenue; 5) I Can’t Stop Loving You; 6) Come

Back To Me (My Love); 7) Blue Angel; 8) Raindrops; 9) (I’d Be) A Legend In My

Time; 10) I’m Hurtin’; 11) Twenty-Two Days; 12) I’ll Say It’s My Fault; 13*)

Uptown; 14*) Pretty One; 15*) Here Comes That Song Again; 16*) Today’s

Teardrops. |

||||||||

|

REVIEW Although Roy Orbison’s

professional career properly begins as early as 1956, with the recording of

‘Ooby Dooby’ for Sam Phillips’ Sun Records, it would not be until late 1961 —

already after Roy had become a rising star at Monument Records — that Sun

would bother putting some of those early, rockabilly-era recordings onto an

actual LP. Thus, technically, Roy

Orbison Sings Lonely And Blue became the singer’s first album, even if

stylistically it already represents the second

stage of Roy’s career, in which, after his only semi-successful stint as a

rockabilly artist, he reinvented himself as a pop troubadour — and never ever

went back. Roy’s rockabilly-era Sun output will be covered later, in the

review of At The Rock House; for

now, we shall skip it, as well as Roy’s two formative singles during his even

shorter stay at RCA, and proceed straight to the beginning of a new life. |

||||||||

|

That new life,

for all purposes, begins with ‘Paper Boy’, released as a single on September

28, 1959 — from a certain point of view, the single most important song in

Roy Orbison’s history. RCA did not let Roy issue it, for reasons that seem

rather unclear to me: it would have been one thing if the label truly wanted

their new acquisition to go on putting out «rocking» material, but they did

not — by late 1959, the emphasis on rock’n’roll was already fading away, and

solid, catchy pop songs were all the rage, so I am not exactly sure what it

was that they found so wrong about ‘Paper Boy’. In the end, Roy took it with

him to the Monument label, and although the song did not chart (so maybe RCA

were right about it all along?), it still heralded the arrival of «Troubadour

Roy», with typically symptomatic lyrics: "I walk down to the blue side of town / Where there’s no happiness, no

joy". Prepare yourself for some tight bonding with the word ‘blue’,

which, judging by the frequency of its appearance in Roy’s lyrics, must have

been his favorite color (I can almost picture the man dressing in it from

head to toe one day and dubbing himself "The Man In Blue", then

going on a joint tour with his former Sun Records partner as The Man In Blue And The Man In Black). Although ‘Paper

Boy’ already featured the basics of Roy’s musical aesthetics and was recorded

with the Nashville A-Team that would become his standard vehicle for

everything, it is not yet fully typical of the early Roy Orbison sound. For

one thing, there are no strings, which would soon become an essential

component. For another, The Voice is not quite there yet; Roy still sounds

like a human being rather than a supernatural force, not having quite found

those registers and frequencies that Mother Nature granted him at birth, but

with the stipulation that he’d have to eventually discover them by himself.

(Ironically, Jack Clement at Sun Records allegedly told Roy that he would

never succeed as a ballad singer — and given his data at the time, he was

probably correct about it). But the direction indicated by ‘Paper Boy’ is

already quite promising: write a song that merges together the pop styles of

the Everly Brothers and Buddy Holly, give it a relatively tasteful guitar and

brass arrangement, soak it in romantic melancholy, and there you have it — a

pop music Schubert is born for the upcoming decade of teenage entertainment.

(Curiously, the B-side ‘With The Bug’ still remains an umbilical cord tying

Roy down to his rockabilly roots — it’s a fun enough dance number, but

neither too original melodically nor bringing out the best in Orbison’s

voice). After ‘Paper

Boy’ failed to make the grade, Roy decided to try out a slightly more

optimistic vibe with ‘Uptown’, his first significant collaboration with future

long-time partner Joe Melson. The song is usually quoted as more or less

inventing the classic Roy Orbison sound — with its heavily prominent emphasis

on both lead and backing vocals (due to engineer Bill Porter’s strategy of

building the song up starting with voices rather than instruments) and its

clever use of orchestration; by «clever» I mean not having the strings carry

the entire melody, as Snuff Garrett did with Johnny Burnette, but rather

engaging in occasional dialog with the singer, playing short, hook-like

phrases with a bit of a «shocking» effect. The only problem was that for an

upbeat, positive-energy-loaded song like ‘Uptown’, whose lowly-boy-dreams-big

lyrics sounded as if they were tailor-made for Eddie Cochran ("It won’t be long, just wait and see / I’ll

have a big car, fine clothes / And then I’ll be / Uptown, in penthouse number

three"), Roy’s vocals were hardly the best fit, even if he did live in a tiny apartment with his

wife and son at the time and "one

of these days, I’m gonna have money" was far from a meaningless line

for the man. Still, the vibe properly requires a stinging, aggressive, hungry

vocal delivery, and Roy... well, Roy was just too much of a gentleman in a

suit to provide. He’s far more

indispensable on the largely — and totally unjustly — forgotten B-side,

‘Pretty One’, a slow ballad that sort of fell through the cracks but is

actually the very first proper showcase of Roy’s vocal range and his classic

technique of emotional build-up from the lower to the higher octaves. It’s a

smooth, but tremendously dynamic journey from the bottom grim a cappella

accusation of "Hey there, pretty

one / Take a look at what you’ve done" to the crowning

broken-hearted falsetto of "Remember

I still love you", and even if similar and technically more stunning

journeys would be waiting in the future, I am a little puzzled about why

nobody ever talks about ‘Pretty One’ as the starting point of Roy’s

impeccably Apollonic «multi-storied vocal towers». Give the lowly B-side a

break! It is, in fact,

the very same strategy that he employs for ‘Pretty One’ which would soon be

followed on the far more successful ‘Only The Lonely’ — there, too, Roy

makes you wait for the final verse to unleash his full potential. "Maybe tomorrow — a new romance — no more

sorrow — but that’s the chance — YOU GOTTA TAKE": these are the

twenty seconds of singing that finally sold Mr. Orbison to audiences across

both sides of the Atlantic. It’s funny, but I seem to detect just a tiny bit

of vocal cracking at the beginning of the cha-a-a-a-nce

bit, as if Roy was overstretching his natural range (or simply not yet having

it fully trained); but even if it’s my brain playing tricks on me, there’s no

denying that the quasi-operatic style that Roy demonstrates on ‘Only The Lonely’

has a much rawer, «homebrewn» feel to it than, for instance, the glossy

polish of Elvis on ‘It’s Now Or Never’. Ironically, ‘Only The Lonely’ is said

to have been initially offered to the King and rejected; I’m sure that it is

only a matter of time now, in our advancing age of artificial

pseudo-intelligence, before we hear how the song could have sounded in Elvis’

version, but, you know, Elvis doesn’t really do the broken-hearted vibe too

well. Actually, even

more ironic are the obvious musical similarities between ‘It’s Now Or Never’

and ‘Only The Lonely’, set to pretty much the same rhythm; in fact, once the

melody stops for the first time you almost expect Roy to pick up "it’s now or never...".

Inevitably, there’s a bit of that Neapolitan romantic corniness attached, and

I am also not a big fan of the dum-dum-dum-dumdy-doo-wah

oh-yay-yay-yay backing vocals which sound as if they are uninvited guests

from some Jan & Dean baby-talk universe rather than natural shadows of

Roy’s broken-hearted delivery; on the other hand, it is hard to suggest any

proper alternatives, because the song’s mood sort of requires Roy to have a

conversation with a bunch of shadows on the wall, and if the Anita Kerr

Singers could not find any more, uhm, respectable

syllables to vocalize, then so be it. But maybe they should have gotten The

Jordanaires instead. In any case, it’s ‘Only The Fuckin’ Lonely’, right? One

of those songs where critique is useless even if you hate it, which I

certainly don’t. Predictably,

the sequel to ‘Only The Lonely’ followed the same formula and, consequently,

was quite a bit inferior. The most notable thing about ‘Blue Angel’ is that

it marks the first appearance of the word blue

in the title. Other than that, it has the same cha-cha-boom rhythm as ‘Only The Lonely’ (and, by extension,

‘It’s Now Or Never’), the same interplay between Roy’s lead and corny-and-even-cornier

backing vocals (instead of dum-dum-dum-dumdy-doo-wah,

we now have sha-la-la-dooby-wah,

dum-dum-dum-yeh-yeh-um, which is definitely more sophisticated but not

necessarily «transcendentally progressive», if you get my meaning), and the

same «sit-tight-until-the-end!» trick where Roy unleashes his full power on

you in the final bars. The most important shift is that the mood here changes

from broken-hearted to courteously suave (Roy is now playing the outsider

consoling the broken-hearted partner), and this puts the song into a slightly

sleasy mode, playing up the smooth operator angle rather than the tragedy. In

a strange display of adequate taste, the buyers were less enthusiastic about

‘Blue Angel’ than its predecessor, though it still made the Top 10. Even less

successful was ‘I’m Hurtin’, Roy’s third and last single from the same year —

it corrected the potential mistake of ‘Blue Angel’, returning the man to pure

broken-hearted mode, but it was simply way

too close to the original formula of ‘Only The Lonely’. All they did was

slightly speed up the tempo and make the arrangement a little fussier, with

the big bass drum pounding out Roy’s heart rhythm and the swirling strings

tickling our emotional centers right off the bat and all through the song. It

was really one of those «if you loved ‘Only The Lonely’, you’ll also love...»

moments, but sequels are just sequels, and even lyrically, the song does not

pretend to be anything but a sequel: "Time goes by / Right on by / And I’m still hurtin’". Yep,

and Peggy Sue got married not long ago. #27 on the US charts and no chart

position at all in the UK — and I couldn’t really protest. Even so, the

smash success of ‘Only The Lonely’ and the slightly less smashing success of

‘Blue Angel’ earned Roy the right to finally put out an entire LP of material

— an LP which would, almost algorithmically so, entitled Roy Orbison Sings Lonely And Blue, although, admittedly, it’s not

really a bad title because Roy does

mostly sing lonely and blue, no doubts about it. All of the three singles

would be included, but it would also give the man a chance to branch out and

try something riskier (well, faintly

riskier) and not straightforwardly directed at generating sales. Since the

Melson-Orbison songwriting plant still claimed to put quality over quantity,

this would also mean having to rely on outside songwriters and covers, but

with their brand new individual sound, that would not necessarily be a

problem. In any case,

out of the three additional original numbers only one, ‘Come Back To Me (My

Love)’, is a rather shameless and inferior (though still pretty-sounding)

rewrite of ‘Only The Lonely’. ‘Blue Avenue’, on the other hand, while it

could also be accused of being just a rewrite of ‘Uptown’, improves on that

upbeat vibe in every respect — particularly in its inspired use of strings,

which, in the bridge section ("oh,

Blue Avenue, yeah I’m feeling so bad") play up a veritable

«thundercloud» pursuing the singer. This is basically a downer version of

‘Uptown’, retaining the former’s toe-tappiness and catchiness but adding extra

drama, and that is precisely the

way you do formula if you think you have to do formula. In my own best-of

collection, ‘Blue Avenue’ easily replaces ‘Blue Angel’, unless I screw up and

mess up the two titles. Also not to be

overlooked is ‘Raindrops’, a song credited exclusively to Melson — it is

utterly different from every other original on here, sort of a country-waltz

turned art-pop with the addition of «raindrop-like» chimes (I’m not sure why,

but somehow chimes and vibraphones always give an «ennobling» rather than

«cornifying» aura to whatever song they’re in, unlike strings, who really have to work hard to prove

their highbrow pedigree). No Olympic feats from Orbison’s voice on here, but

the stylistical difference from everything else feels refreshing, and the

song’s babylike cuteness is so fragile and vulnerable, you feel like you want

to cuddle with the tune rather than brush it off. The covers, as

befits a pop artist recording in Nashville, are mainly pulled off from the

country circuit, with Roy sometimes reaching over to decade-old hits like

‘Cry’ (well, any song with the line "and

your blues keep getting bluer" is sure to tickle our hero’s fancy),

but also showing a real affection for more recent country hitmakers such as

Don Gibson. I’m not really sure if there is such a big need for Roy’s cover

of ‘I Can’t Stop Loving You’, but I do have a soft spot for his take on the

appropriately gloomy ‘(I’d Be) A Legend In My Time’, on which he really feels

himself like a fish in water, giving it extra depth and power, particularly

on the final line of the chorus, where he dips into an almost sardonic

barytone (like an "oh yeah, you thought Don Gibson wrote a song for

himself? well, you ain’t heard nothing yet,

make way for me, the true king of

feeling lonely and blue!"). Ultimately,

there is just one big thing that is wrong with Sings Lonely And Blue, and it is already symbolized by its title:

despite all of his innovative approaches to the essence and image of a pop

artist, the one thing that Orbison still shares with the Fifties’ generation

is his willingness to lock himself into and firmly confine himself to that

one particular image. If we take up — you knew this was coming, didn’t you? —

the inevitable comparison with the Beatles’ debut across the Atlantic two

years later, there is no denying that Orbison already comes across as an

accomplished professional on this record, while the Fab Four are just

juvenile amateurs by his side (and I’m pretty sure that they correlated more

or less in the same way on their famous joint tour of the UK in 1963). More

than that, he’s got a strong, individual artistic identity, writing his own

songs and recreating most of those covers in his own image — something the

Beatles also tried to do from the beginning, but it’s much harder, really, to

believe that Lennon and McCartney really lived

out the emotions in songs like ‘P.S. I Love You’ or ‘Ask Me Why’ the same

way Roy sounds fully sincere and convincing on ‘Only The Lonely’ or ‘Blue

Avenue’. And yet, the

way I feel it, there is one big difference between Sings Lonely And Blue and Please

Please Me that is responsible for the fact that Roy Orbison would remain

Roy Orbison, and the Beatles would go on to become the most symbolic band of

the new decade. Roughly speaking, Sings

Lonely And Blue is a closed system.

It gives you a self-sustained, accomplished artistic portrayal to which, in

the future, many new details and depth-enhancing improvements would be added,

but the essence of which would never truly evolve or expand. This is Roy Orbison, so much so that you

shall always know what to expect of him in the future: moody, beautiful,

sophisticated broken-hearted pop music with that wonderfully lilting Voice on

top. Please Please Me, on the

other hand, is the very epitome of an open

system — a band that tries out a half-dozen different formulae at once,

some of which naturally work better than others but all of which, taken

together, send out an inspiring message that — to paraphrase and invert the

line we all know — there’s nothing you

CAN’T do that CAN be done. In other words, you could probably build an AI

that would, more or less correctly, predict post-1960 Roy Orbison if you fed Sings Lonely And Blue into it, but

you certainly couldn’t do the same for the Beatles if you only fed it Please Please Me and its surrounding

singles. Even so, there

are formulae and formulae, and at least Roy’s included such parameters as

«diligent songwriting» and «trying out new musical ideas» as one of its

foundations. As we can already see, he was not completely above rewriting his

own hits or occasionally falling into a rut, but (a) his guilt here is far

less than that of many others and (b) his sense of taste and understanding of

the concept of beauty is pretty much infallible, so that even the most

obvious self-repeats still sound wonderful, at least on a purely formal

level. And if you love The Voice — as in, really love love love it — do not limit yourself to best-of

compilations; settle for nothing less than the entire catalog, starting with

this perfectly fine sample. |

||||||||

![]()

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Album

released: December 1961 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) This Kind Of Love; 2) Devil Doll; 3) You’re My Baby;

4) Tryin’ To Get To You; 5) It’s Too Late; 6) Rock House; 7) You’re Gonna

Cry; 8) I Never Knew; 9) Sweet And Easy To Love; 10) Mean Little Mama; 11) Ooby Dooby; 12) Problem Child; 13*) Go! Go! Go!;

14*) Chicken Hearted; 15*) I Like Love. |

||||||||

|

REVIEW I suppose that prior to December

1961, only the most knowledgeable and musically hungry teens in America knew

that Roy Orbison’s original occupation was to make certified rockabilly

records for the Sun label. Between 1956 and 1957, as lead singer and guitar

player for his own little band (formerly The Wink Westerners, later renamed

to The Teen Kings once Elvis became a thing), he cut four singles for Sam

Phillips, only the first one of which made any visible impact on the charts

(‘Ooby-Dooby’); the rest were pretty much ignored both by the public and Sam

himself — actually, Sam’s attitude toward most of the artists he’d worked

with after Elvis’ defection to RCA can be more or less summarized as going

through three stages: [a] «could he be the next Elvis?», [b] «nah, he

couldn’t be the next Elvis», [c] «what’s this guy still doing in my studio?».

Some of those artists, after they’d left Sun and became big stars on their

own, merited a Stage D: «oh, they made it big with somebody else, well, they

have plenty of stuff left in our vaults, so let’s get it out now». Such was the fate of Johnny

Cash, for instance, and the same happened to Roy Orbison, with a 12-song LP —

more than half of which came from the archives — released in late 1961, by

which time Roy had been a steady hitmaker for Monument Records for more than

a year. Now all those new fans of

America’s hip young modern artist could hear what he’d been up to five years

earlier — except, of course, most of them weren’t really interested, and not

even Roy himself could probably blame them. |

||||||||

|

Much like Cash,

Roy would not completely renege on his rockabilly roots throughout his career

— as late in his life as 1988, he would quite joyfully perform ‘Ooby-Dooby’

and ‘Go! Go! Go!’ live on stage (as captured on the excellent Black & White Night

Live DVD), rather than wipe that stage out from his memory. Yet it

probably goes without saying that, of all the young rockabilly artists trying

to make their mark on the world in the wake of ‘Rock Around The Clock’ and

‘Heartbreak Hotel’, Roy Orbison must have been one of the oddest cases. Never

a particularly great guitar player, never the kind of singer to be able to

raise hell with his vocal chords, never a pelvis-thrustin’ sex symbol on the

stage, the young Roy Orbison was a humble, bashful kid who could certainly love this kind of music — heck, I love AC/DC and I’m probably farther

removed from the average stereotype of an AC/DC fan than from the Sun — but

who was tremendously underequipped to perform it, and that’s putting it

mildly. Blaming Sam Phillips for failing to promote those flops is pointless;

there was not a chance in hell anyway that they’d be able to withstand competition

with the likes of Gene Vincent or Sun’s own Jerry Lee Lewis. Even Bob Dylan,

with his Golden Chords from his teen days at Hibbing, might have had a better

stab with this while his primary idol was still Elvis rather than Woody

Guthrie. Even so, Roy’s

short and commercially disastrous rockabilly period was not completely

pointless. It did leave us with ‘Ooby Dooby’, a song originally written by

aspiring Texan songwriters Dick Penner and Wade Moore that somehow fell into

the hands of Roy Orbison and his «Wink Westerners» as early as 1955. The song

itself is nothing special — it clearly models itself after ‘Tutti Frutti’,

toning down the sex aspect of the latter and making it a little safer for

general consumption — but Roy’s merit here is the brilliantly constructed

lead guitar break, showing how much, perhaps on a subconscious level, he was

already craving for Apollonian harmonic perfection even while playing

supposedly «wild» rock’n’roll. He probably took Carl Perkins as his role

model, but the guitar breaks on ‘Ooby Dooby’ are cleaner, more precise and

thought-out than just about anything I’ve heard from Carl, even if it does

not make them automatically superior. Years later, John Fogerty would

recognize Roy’s goals and, with the aid of more modern production and a

slightly better technique, take them even further on his tributary cover of the

song — but do take note that John essentially just copied Orbison’s solos

almost note-for-note, something he’d be rarely interested in doing when

taking on other artists’ songs. (Somewhat

off-topic, if you want to hear a somewhat different

take on ‘Ooby Dooby’, it’s a good pretext to get acquainted with a little bit

of Janis Martin, who

was, for a short while, promoted by RCA as the «Female Elvis» — before she

eloped with her boyfriend, got pregnant, and forever ruined her prospects of

a successful American career, leaving Wanda Jackson and Brenda Lee to reap

the seeds she’d sown. I think that might be Grady Martin backing her on lead

guitar on this recording, and he devises his own solos rather than copying

Orbison’s — pretty sweet, but mainly just going to show how perfect the

original ones were in the first place. Unfortunately, Janis never made it big

because most of her songs were straightforward rewrites of popular rockabilly

hits with new sets of lyrics — but she does deserve some recognition due to

her pioneering effort). Anyway, ‘Oooby

Dooby’ was cutesy-cool, and, arguably, its B-side, ‘Go! Go! Go!’, may have

been even better, with the Teen Kings really putting on the speed and Roy

making the first triumphant demonstration of his vocal range, moving up an

octave in the chorus to raise the level of rock’n’roll hysteria as high as

possible. It was also his first proper songwriting credit, though, honestly,

the song is more or less just a variation on Hank Snow’s ‘I’m Movin’ On’ —

it’s not the compositional genius that matters here but the level of

stomping energy, unusually impressive for a timid guy like Roy. (The song

would later be covered by Jerry Lee Lewis as ‘Down The Line’, but

the Killer would just convert it to his usual Killer style like he did with

everything else). And that was

it. ‘Ooby Dooby’ charted — a little bit — and sold — enough to let Roy keep

his contract with Sun and continue cutting records with the label — but

nothing that followed made any impact. ‘Rockhouse’, from September 1956,

feels less like an attempt to repeat the alluring primitivism of ‘Ooby Dooby’

and more like a conscious mimicking of Elvis’ last singles for Sun, such as

‘Baby Let’s Play House’, which does not work for Roy because his voice simply

refuses to provide the same effects that Elvis’ does — as energetic and

danceable as the song is, Orbison sounds like a struggling imitator here, and

even the guitar breaks feel like a poor man’s replacements of Scotty Moore’s

talents. The B-side, ‘You’re My Baby’, was even speedier, and I really dig

the fast chuggin’ interplay between rhythm and lead guitars, but the vocals

just don’t work. With the

‘Rockhouse’ single flopping, Roy tried to go for something different on his

next release and came up with ‘Sweet And Easy To Love’, a comparatively

gentle pop-rock song more reminiscent of Buddy Holly than Elvis — although,

to be accurate, the single came out in March 1957, by which time ‘That’ll Be

The Day’ had not yet been released and nobody really knew of Buddy Holly...

well, come to think of it, ‘Sweet And Easy To Love’ sounds more like a Carl

Perkins country number with comparatively croonier, Buddy Holly-esque vocals.

The old-fashioned doo-wop harmonies surrounding Roy’s lead vocal sound

positively moronic, though. The B-side, ‘Devil Doll’, slows things even

further, for the first time ever placing 100% emphasis on vocals, both

backing and lead — and perhaps it could have really been something with

better production, but the usual Sun limitations apply here rather painfully,

so that the song ultimately becomes a muffled mess, sounding like Roy was

singing it from down in the cellar, separated from the mikes by a thick layer

of concrete. (Somehow this approach sometimes worked in the case of Elvis,

but Roy Orbison’s voice is just not powerful enough to get such rough

treatment). The shift of approach did not help; the record became another flop,

prompting Roy to briefly return back to the classic rockabilly format and

outside songwriters. His last single for Sun (December 1957) was one of the

oddest records in his «archaic» catalog: ‘Chicken Hearted’, driven forward by

laconic, lashing-out electric guitar bursts and occasional patches of lead

sax that take their cues from Little Richard’s ‘Keep-A-Knockin’ and ‘Slippin’

And Slidin’, is close to being a fully instrumental blues-rock groove — and

the lead guitar break sounds like Roy Orbison inventing Neil Young lead

guitar à la ‘Down By The River’ twelve years before the occasion. Most

interesting is the fact that the original song, credited to Bill Justis (best

known as the composer of ‘Raunchy’, the instrumental that famously got George

Harrison accepted into the Beatles), apparently featured a complete set of

«anti-hero» lyrics ("My girlfriend

slipped and fell / Now she’s hanging from a cliff / I can’t come to her

rescue / But these flowers I must sniff"), and there is even a rare outtake version

of the song featuring Roy mumble them out incomprehensibly — but on the final

cut, he decided to throw them out and just go with the absolute minimum.

Possibly because the lyrics were quite biting for their time: "Mama’s in the workshop / Daddy’s in the

jail / I seem to be afraid / To go to work and make their bail" —

just a short step from here to something like ‘Tombstone Blues’, but young

Mr. Roy Orbison was apparently too chicken-hearted to pioneer it. In any case, the final result is quite quirky and, perhaps, the closest

Orbison ever came — accidentally — to patenting his own brand of rockabilly;

but this very oddness made the song ineligible for any potential chart

success even if Sam Phillips were to heavily promote it, which, of course, he

did not. The B-side, ‘I Like Love’, written by Jerry Lee Lewis’ main songwriter

Jack Clement, was much more stereotypical and would have made decent fodder

for the Killer, but sounds expectedly unconvincing when delivered by Roy;

‘Chicken Hearted’ would be much closer to his true heart than having to

sleazily bark out "I LIKE IT!"

when it’s simply not the man’s natural style. And that was all she wrote, that is, until Roy’s career at Monument

Records started picking up and Sam Phillips suddenly woke up from his slumber

and remembered he still had a bunch of unreleased stuff from Roy Orbison and

the Teen Kings lying around in Sun’s inexhaustible vaults. The resulting

album, At The Rock House, included

most of the aforelisted A- and B-sides (though, inexplainably, not ‘Chicken Hearted’), plus seven

more songs, most of which are conspicuously softer and more melodic than the

energetic rockabilly stuff Sam wanted Roy to release officially — except for

‘Mean Little Mama’, which sounds inspired by Elvis’ ‘Got A Lot O’ Living To

Do’, and ‘Problem Child’, which tries to marry the guitar style of Chuck

Berry to the vocal style of Elvis. Both songs are fun, if you are able to

look past the usual dreadful standards of tinny production on Sun Records —

vocals and instruments all sound as if they were wrapped in half a dozen

blankets. As for the softer material, direct competition with Elvis on a cover of

‘Trying To Get To You’ does not quite work in Roy’s favor (although he does

give the song a predictably more subtle and nuanced reading); ‘It’s Too Late’

is sweet, but rather unnecessary in light of the already existing Chuck

Willis and Buddy Holly versions; and the other three songs are early stabs at

original pop-rock songwriting, marred by a little too much recycling of

pre-existing ideas and the usual low production standards — perhaps an

important step forward in Roy’s personal history, but too much of this stuff

feels as if there was always this constant pressure on Roy to become the

ersatz Elvis for the label, and it’s not highly likely that he ever felt

comfortable about this. On the other hand, he did later remember that there

was a considerable amount of freedom during his years with Sun — at least,

freedom to write and record, if not freedom to publish. In the end, though, Roy’s rockabilly years are still bound to remain a

charming footnote in his personal history. Roy was never a genuine rocker by

his true nature, even if he undeniably loved rock’n’roll («loving» something

and «being a part of it» are two completely different things, though), and it

is only through his overall talent and professionalism that ‘Ooby Dooby’,

‘Problem Child’, ‘Chicken Hearted’ and the other highlights on here remain

listenable and enjoyable after all these years, provided you can look past

the production muck. Admittedly, At

The Rock House is still a pretty good place to assess Roy’s talents as a

team player in a rock’n’roll band: The Teen Kings at their best put up a hell

of a tight groove, and, ironically, there are few spots in Roy’s discography

where you can hear him play a meaner, leaner, speedier guitar than he does on

some of these cuts (that’s one advantage he sure holds over both Elvis and Johnny Cash, his chief

rockabilly competitors on the label). But heroes of early rock’n’roll are

rarely judged by the amount of discipline and practice in their guitar

playing — more often than not, they’re judged by the intensity of the fire in

their spirit, and although Roy had plenty of intensity, it just wasn’t the

kind of intensity that made you want to smash your chair over your neighbor’s

head, which is the kind of noble goal that every noble rock’n’roller

typically aspires to reach. For the sake of completionism, it is also necessary to mention Roy’s very

brief stint with RCA Records, which signed him up after he’d left Sun —

perhaps somewhat mechanistically, hoping that they were making the same kind

of right move when they lured Elvis away from his original makers. Roy only

put out two singles for the label, both of which flopped and got him quickly

canned, but both represent an important chunk of progress for the man: ‘Seems

To Me’ and ‘Sweet And Innocent’ are smooth pop songs with heavy emphasis on

Roy’s soothing vocals, and although the hooks are weak, the style is already

much more close to his Monument era than to the Sun rockabilly one. ‘Almost Eighteen’,

released in January 1959, has a bit more rock’n’roll energy, and the Felix

& Boudleaux Bryant-penned ‘Jolie’ is a cutesy French-tinged pop ditty

that is hard to take seriously but even harder to get offended about. Most

importantly, though, all four of these sides were personally produced by Chet

Atkins, and this means that they sound awesome

next to the muddy waters of Sun’s production — crystal clear guitars,

perfectly audible vocals with every overtone registering ideally in your

mind. Nothing against Monument’s Fred Foster, who did a fine job helping

people properly discern the uniqueness of Roy’s voice, but I sure wish that

partnership with Chet could have gone on for at least a little longer. It’s still a bit of a scholarly question — just exactly how much had the

«Sam Phillips School For Beginning Artists» helped shape and nurture Roy’s

artistic persona for the big things to come in the future. I do suspect that,

career-wise, had Roy stuck from the very beginning to writing melodic pop songs,

he might have ended up as Carole King — peddling his services to other

artists for a decade or so before gathering the courage and grabbing the

opportunity to launch his own artistic career. The rockabilly market, being

far more of a D.I.Y. sort of thing back in the Fifties, gave artists a better

chance to speak up for themselves than the already far more

corporate-controlled pop business, so that, by the time Roy decided to make a

decisive shift to pop, he had already established a sort of reputation as a

singer and player, not just a composer. In other words, it may be so that

without ‘Ooby Dooby’ we would not have ourselves an ‘Oh! Pretty Woman’ — at

least, not as it was recorded in 1964 by Roy Orbison, rather than somebody

else at some other time. Then again, (a) this is just educated speculation on

my part, and (b) this has nothing to do with the far more important question

of whether there is still a reason to listen to, or a possibility of enjoying

an album like this in the 21st century... and ultimately, it probably all

depends on just exactly how chicken-hearted you feel in this day and age,

dear reader. |

||||||||

![]()

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Album

released: January 1962 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) Crying;

2) The Great Pretender; 3) Love Hurts; 4) She Wears My Ring; 5) Wedding Day;

6) Summersong; 7) Dance; 8) Lana; 9) Loneliness; 10) Let’s Make A Memory; 11)

Nite Life; 12) Running Scared. |

||||||||

|

REVIEW For Roy Orbison, 1961 might have

felt like the best year ever in his musical career — even if that year only

yielded two new singles, with a hot new LP on their tail delayed until the

first month of 1962. But it was precisely those two singles which not only

proved to the world that Mr. Orbison was not going to remain a one-hit

wonder, but also that Mr. Orbison was somewhere on the verge of

revolutionizing pop music as a whole. With «sensitive art-pop for the younger

generation» still being in its infancy, 1961 saw Roy stepping out as its

principal troubadour, offering a much fresher, more creative, inventive, and

genuinely emotional alternative to the «mature» (a.k.a. «stiff and

old-fashioned») phase of Elvis Presley’s career. He did not have what it

really took to send that younger generation into the throes of total frenzy —

the added touch of crude rock’n’roll energy — and his singing voice was

really as much of a curse as it was a blessing, since its naturally plaintive

overtones kept sending him over and over again into the trap of the same

stylistic formula. But within those limitations, 1961 made Roy the absolute

monarch of that formula. |

||||||||

|

I am not aware

if the rhythmic pattern of the Bolero (in its classical, Ravel-style form,

not the faster and more danceable Latin one) was first employed within pop

music in ‘Running Scared’ or not. I am

aware that I myself know of no earlier examples — and the fact that the

entire song is essentially one long chorus-less crescendo, gradually building

up in power and intensity until Roy gets his triumphant release with that

legendary high A, reinforces the Ravel analogy and further proves that Roy

and Joe Melson were intentionally raising the stakes, aiming for ambitious,

operatic teenage drama on a whole new level compared to ‘Only The Lonely’. On the whole, I

find the song a bit too rigid to genuinely fall in love with it, but maybe

this is precisely because it puts such a heavy focus on its construction, going more for symbolism

than raw emotion — and that’s okay, because sometimes you have to first

shatter the form so it can be later filled up with new content. There is no

chorus or bridge section here in the traditional sense, but the song does

shift from the key of A to D around the 1:30 mark, becoming more dynamic and

even mildly danceable precisely at the second when the subject matter moves

from the protagonist’s internal torment to the actual «moment of truth» —

this is as close to a «bridge» as the song gets, except that the bridge ends the song, eventually returning

back to the now-triumphant A as the girl of Roy’s dreams makes the right

choice and walks away with the shy, reticent nerd instead of the hunky

captain of the football team (or something like that). Many people call ‘Running

Scared’ a «two-minute opera», which is clearly an exaggeration (the honor of

being the first two-minute teenage opera should probably go to the likes of

‘Remember (Walking In The Sand)’), but it is certainly not a coincidence that

they tend to instinctively exaggerate in that

direction. Clearly, the song is just a note-perfect symbiosis of melody,

arrangement, lyrics, and vocals, on a level of ambition and intelligence

rarely, if ever, heard of at the time; an almost too ideal template for an

art-pop song that could diminish even the Beatles’ reputation (certainly the

Beatles would not reach that level of structural sophistication until their

«mature» period). Unfortunately,

the one thing that the impact of ‘Running Scared’ truly diminished were

memories of the B-side, a cover of Boudleaux Bryant’s ‘Love Hurts’ that had

only recently been released by the Everly Brothers. Stuck in between the

famous original and the much later — and the much more over-dramatized,

Seventies-style — Nazareth cover, Roy’s performance might arguably be the

best of the three. The Everlys, with their quiet and intimate harmonies, sang

it as a sort of soothing consolation for desperate lovers; their "I really learned a lot, really learned a

lot" feels like young wisdom they pass on to you over a two-minute

long hug. With Roy, though, you can probably predict even if you have not

heard the song that it is going to be dramatic and deeply personal; and while

I can guess that the sentimental strings and chimes might cause some

demanding listeners to wrinkle their noses and run back to the safe hills of

the Everlys’ sparsely arranged version, they are quite a natural fit with the

timbre of Roy’s voice. So if you’re down on your luck and you need a couple

of motherly figures, Phil and Don offer their services; but if you want

somebody to amplify your own

feelings for you, Mr. Orbison can be a puffed-up version of you for the measly price of... well,

whatever amount you had to put in the jukebox back in 1961 (except that most

people probably went for the A-side anyway). With critical

and popular tastes on the same line, ‘Running Scared’ hit No. 1, showing

Orbison and Melson that they were finally on the right track — so it is not

at all surprising that their follow-up to the big hit would go for more or

less the same formula, even sticking to the same bolero-like rhythmic pattern

and rehashing the trick of the final triumphant high note after a long

crescendo. What is surprising is

that usually this commercial pattern results in failure (either total or

relative to the high start) — but every rule knows its exceptions, and in

this case ‘Crying’ turned out to be the superior song, or at least every bit

as vital as its predecessor. The reason is that while it is similar, it is

also quite different — even more operatic, with a vocal melody that goes

through so many twists and turns that it can only afford to repeat the total

pattern twice (and even then, with some variations in the second run). ‘Crying’ is

probably the greatest song Roy ever wrote and performed, just because it

feels like such an ideal photoshoot of his complex artistic personality. It’s

great right from the start: there’s the frozen-in-ice melancholic-emotionless

state of mind ("I was all right for

a while / I could smile for a while...") immediately triggered and

shattered by the protagonist’s fateful re-encounter ("But I saw you last night / You held my

hand so tight...") — Roy not only rises higher in pitch here, but

gulps down a pint of extra gentleness so we know the «emotionless frown» is

just a front. Then there are the several different ways in which he

articulates the word "crying",

almost as if mulling it over, seeking out all the different ways in which a

grown man can shed tears. There is something magical in the way he repeats

the word in the (pseudo-)chorus — crying,

crying, crying — without even once breaking into anything that would

resemble real crying (which would

have been a cheap theatrical gimmick), but with each repeated instance of the

word somehow, I don’t know, paying religious homage to the ancient art of

crying, if you get my drift. There are enough subtle overtones here to make

up for a good dissertation in the field of emotional psychology. And then

there’s the grand finale, patterned after ‘Running Scared’ but twice as

intriguing. See, the end of ‘Running Scared’ depicts an actual, 100%

certified triumph — simply by being himself, the guy gets the girl and

emerges victorious. ‘Crying’, on the other hand, starts out as a tragedy and

ends up as a tragedy, yet its coda ends on the same note of emotional triumph

as ‘Running Scared’ — "walked away

with me!..." and "crying

over you!..." aim for the exact same emotional response from your

brain, despite telling seemingly two opposite kinds of stories. Now the

simplest solution would be to think of it as a technical flaw on the side of

‘Crying’, where the songwriters were told «we need the song to end exactly

the same way as your previous big hit» and they had no choice but to go ahead

and do just that. But as a listener who has every bit the same right to

interpret art as its creator, I opt for a much more interesting solution —

being a eulogy ode to, well, crying, ‘Crying’ ends on a triumphant note

because the protagonist wants to cry.

Because he’s spent half of his life seeking out the perfect way to break his

heart, like other people seek out the perfect way to a perfect murder, and this is his masterpiece — the greatest

love on earth broken and shattered in the greatest way possible, with a heart

destroyed beyond repair once and for all, putting to shame even the most

desperate and suicidal romantics of the 19th century. How’s that for a triumph? There might be far

more psychological disturbance and darkness in the song than we’d normally

care to admit — in fact, I could almost draw a straight line from here all

the way to Nick Cave’s famous "all

beauty must die" from ‘Where The Wild Roses Grow’, though Roy

himself probably would be too terrified to want to accompany me on that train. Although

‘Crying’ got stalled at No. 2 on the charts (for a respectable reason — it

was blocked by Ray Charles’ ‘Hit The Road, Jack’; what a time to be alive,

eh?), its subsequent fame and reputation still overshadowed ‘Running Scared’,

and it was actually used to open Roy’s new LP on the Monument label, while

‘Running Scared’ was sequenced to end it (perhaps because the label

executives thought it would be good to have the album terminate on a positive

note). It was also used for the title of the LP, suggesting to the entire

world that C-R-Y-I-N-G is, in fact,

Roy Orbison’s business, and that business is good like never before. I would

have liked to know who precisely was responsible for putting that Greek-style

tragic mask on the front cover: it’s one of those «okay, Roy, we can’t

actually get you to shed real tears

on your actual face, and even if we could, they’d never allow us to use the

shot for an album cover, so we’re going for artistic symbolism here...

perhaps some serious people might

want to buy this record now, not just that Elvis Presley-lovin’ riff-raff!»

moments. Amusingly, what

they kept off the record was the

B-side of ‘Crying’ — ‘Candy Man’ — which is pretty much everything that

‘Crying’ is not. Co-written by Fred Neil (of ‘Everybody’s Talkin’ fame) and

Beverly Ross (of Bill Haley’s ‘Dim, Dim The Lights’ fame), it is probably the

sleaziest song ever performed by

the Golden Voice. Neil himself stated quite openly that candy man was the preferred appellation applied by New Orleanian

hookers to their pimp, and although the lyrics of the song never provide any

specific hints and, on the whole, pretend for it to merely be about obsessive

courting, I think that Roy got the idea — he does deliver the goods in his

most earnest simulation of the «pimp voice». "Come on woman, gonna treat you right / Give you candy kisses every

single night" might feel almost stalker-ish in this context, if it

weren’t for the fact that there is no evil or mental instability on the radar

— just sleazy light-heartedness, the kind that may be directed from an

easy-going guy to an equally easy-going gal. But while I certainly wouldn’t

want to write Roy off as a one-mood pony, or insist that he was

pathologically incompatible with the idea of «having fun», I am not sure that

he was the most natural candidate in the world for the role of a «candy man».

Over in the UK, the song would become a hit on its own as performed by Brian

Poole and the Tremeloes — who learned it from Roy himself while touring with

him — but they were a mediocre band and their cover is appropriately limp.

The perfect version of ‘Candy

Man’, in my opinion, can be found on the Hollies’ debut album, with Allan

Clarke finally finding just the right delivery tone and getting that

"aah, your own candy-cande-e-e-e... candy ma-a-a-a-n!" to sound

exactly how it’s meant to (which is, presaging the classic message of Lou

Reed’s "I’m just a gift to the

women of this world" years later). I still find it

tremendously hilarious, though, how it is possible to have one and the same

single whose A-side is so totally and utterly in line with the artistic

sensitivities of the 21st century and whose B-side represents just about

everything that these artistic sensitivities of the 21st century are not — the perfect trolling material

for the modern young progressive. (I also love how you can hear both of them

27 years later at the same legendary Black & White Night concert, not

only having lost none of that spark, but even increasing in their efficiency:

‘Crying’ amplifies

Roy’s original voice power to even more unbelievable heights, and ‘Candy Man’ takes a few

hints from all those UK covers to gain in amicable sleaze). Most of the Crying LP was recorded during the

same June 1961 sessions that yielded ‘Crying’, with just a few titles

selected from earlier sessions in May and February of the same year — and

while I agree with Richie Unterberger (writing for the All-Music Guide) that

none of the other songs are up to the same standards as ‘Crying’ or ‘Running

Scared’, I think that on the whole, the LP stands up pretty well. It is true

that far too often, he slips back into old-fashioned formula, but then again,

not every song one writes can be

expected to revolutionize pop songwriting. Expectedly melancholic material

like ‘Wedding Day’ (which, as you understand, never comes to pass) and

‘Summer Song’ (which, as you understand, has come and gone) rests on tried

and true doo-wop chord progressions, but the arrangements are tasteful and

the singing passionate — it’s just that the songs are not distinguishable

from covers of old material such as the Platters’ ‘Great Pretender’, which

Roy succeeds in making his own but not in reinventing it for a new decade. The second side

of the LP is preferable to the first because it adds more diversity: the

A-side is literally five depressing ballads in a row, only interrupted by the

comparatively corny serenading of the Bryants’ ‘She Wears My Ring’ (if you

don’t listen to the lyrics too much, you might mistake it for a depressing

ballad, too, though Roy tries to simulate happiness as best he can). The

B-side, however, throws on a few danceable pop-rock numbers, starting with a

song actually called ‘Dance’, a mid-tempo little twist in which Roy suggests

that his partner put "bells on

your toes" and mentions something about "the dancing fever", even if the song never rises above room

temperature. Still, it’s kinda fun and the Boots Randolph sax solo is

fabulous — and I also think the Rolling Stones ended up totally stealing

Roy’s "dance, baby, dance, come on

dance, baby, dance" for their own ‘Dance Little Sister’ fifteen

years later, even if unconsciously so. Then there’s ‘Lana’,

a cutesy doo-wop rocker that could simply be the blueprint for Sha Na Na’s

entire career if not for (a) Roy Orbison, the master of good vocal taste,

delivering the product and (b) the odd-as-heck fuzzed-out bass line played by

Bob Moore — no idea how they got that tone and whatever possessed them to leave

it in, but the nearly synth-like resulting sound somehow adds a lot of weight

to the tune. For accuracy’s sake it should be added that Roy originally gave

the song to The Velvets, a short-lived vocal group from Texas, but their version swims in

all the clichés of doo-wop without even trying to do something

different. And this one... this one’s got the fat bass sound. It doesn’t exactly

make it the grandaddy of ‘Satisfaction’, but it still makes it nasty enough to survive the cuteness. And then there’s

‘Let’s Make A Memory’, a song that makes me picture Roy Orbison in a sailor

uniform, planning to knock up some unfortunate lady in a faraway corner of

the world: "Let’s make a memory

together / One that will last and last forever" — I mean, that’s

hardly any more or less gross than the message of ‘Candy Man’, but at least

this one is delivered in a decidedly sweeter tone. However, what really catches my ear is not the

lyrics, but the little descending

guitar riff (probably played either by Hank Garland or Grady Martin or

some other guitar wiz from Nashville) that first crops up at 0:34 into the

song and then reappears for the short twenty-second coda. It is exactly the same riff that forms the

backbone of the Beatles’ ‘It Won’t Be Long’ — and is it really a coincidence

that they recorded the song less than two months after their joint UK tour

with Roy Orbison? (Although I am not sure if he ever performed it live, but

certainly the Beatles must have had all the records). Admittedly, the riff is

kind of wasted in this song, so it was good of the boys to pick it up and put

it to good use; but it’s odd that apparently no one seems to have made the

connection earlier. And speaking of

connections, ‘Night Life’ certainly presages ‘Oh Pretty Woman’ with its brass

riff that would later be reworked into the electric guitar melody of Roy’s

trademark song; but more importantly, it also has a complex, somewhat

baffling vocal structure that opens with an anthemic-operatic intro,

magically turns into «grittier» pop-rock, then slowly works its way up to

even more melodramatic-operatic heights, and then comes back full circle to

the original brass riff, tickling the senses of both those who are in lust

and those who are in love. It’s just that it doesn’t have a single,

all-powerful hook, but repeated listens reveal it as another fine exercise in

adventurous songwriting, well worth seeking out. So much for the

LP, which does have its share of filler, but whose worst problem, arguably,

is the decision to put most of the slower ballads on the A-side and most of

the livelier pop-rockers on the B-side — a fairly common decision for the

time, but one that only works if you use your LPs for parties, with 20

minutes of dancing followed by 20 minutes of holding hands in the dark. If

you’re just sitting in the dark,

though, the filler on the A-side, with Morose Roy all over it, will feel

particularly debilitating, and the filler on the B-side, with Toe-Tappy Roy

at the helm, will feel a little silly. I would certainly prefer a different

sequencing, though I do like the idea of placing the two biggest songs as

bookmarks. To complete the

picture, one should probably throw in Roy’s first single from 1962, recorded

around the same time that the LP hit the store shelves — which means that ‘Dream

Baby (How Long Must I Dream)’, written for Roy by famed Nashville tunesmith Cindy

Walker, appeared too late to make it on Crying.

A simple, catchy piece of country-pop, it is worked over by Roy and his band

until they turn it into a fabulous groove, with Floyd Cramer throwing in a

piano line that sounds like a variation on either ‘What’d I Say’ or ‘Lucille’,

and a general feeling of «yeah, this is country, but there’s no way in hell

we’re recording it like a generic country song!» even if we’re still sitting

square in the middle of Nashville City. The B-side, ‘The Actress’, written by

Roy himself, is no slouch either, though it feels as if it were somewhat

assembled from bits and pieces of his previous hits, without any truly fresh

ideas. Summing up, one

might say that Roy Orbison found himself on Sings Lonely And Blue — and then took little old himself as high

as he possibly could with Crying,

stretching that formula to its maximum limits. For a few more years, he would

still give us beautiful songs that were every bit as good as ‘Running Scared’

and ‘Crying’, but there would be no talk of ever surpassing that golden standard.

But I suppose that in 1961–62, not a lot of people could even suspect that it

might ever be surpassed by anyone or anything — and even for the

aforementioned Beatles, writing a song as good as one of Roy Orbison’s must

have been the ultimate songwriting fantasy. Like I said, what a time to be

alive! |

||||||||

![]()