|

The farthest they got was with the title track,

which they nicked from the American songwriter P. F. Sloan — who, at the

time, was a heavily Dylan-influenced aspiring folkie, occasionally recording

his own material but mostly peddling it to outside artists, ranging from Jan

& Dean to Barry McGuire (‘Eve Of Destruction’), the Turtles, and Herman’s

Hermits. He did not have much of an imagination, but the songs were good

enough to serve as passable second-rate Dylan: ‘Take Me For What I’m Worth’,

which Sloan originally

released himself as an acoustic ballad, basically rips its message off of

an uncanny hybridization of ‘Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright’ and ‘It Ain’t

Me Babe’, but the melody is poppier than either of those two, so the original

version does indeed sound like a preliminary demo compared to the full-scale

folk-pop arrangement that the Searchers came up with for it. Sloan’s voice is

stronger and more «epic» than Mike Pender’s, but they get a sharp, jangly

guitar sound going on here that certainly trumps his own guitar strumming.

Most importantly, by taking out the Dylanish

harmonica of the original and by adding group harmonies to beef up the "if you want me you’ll take me for what I’m

worth!" chorus) they succeed in brewing up a bit of garage-flavored

punkish nastiness — though it might not have mattered all that much by the

tail end of 1965, when Bob Dylan had already established a reputation for

being able to add in as much garage-flavored punkish nastiness to his output

on his own, without the need for any copycats to do that for him. Still, as a

somewhat more melodic and a tiny bit more sentimental (rather than purely

cynical) alternative to the don’t-mess-with-my-life-woman message of that

particular Dylan incarnation ‘Take Me For What I’m Worth’ is a song that

deserves to be remembered. And as an unintentional metaphor, it also works as

a pretty telling swan song for the Searchers as a band: "And if you think about me in your lonesome

hours / And on your lips there’s a sweet word and not a curse / Then I’ll be

comin’ back one day when my wandering is over / If you want me you’ll take me for what I’m worth". Egotistic

and humble at the same time. I like it.

This certainly does not imply that the rest of the

album is unworthy of your attention. If anything, it is even more polished

and disciplined and tighter-classier-sounding than anything they’d done up to

that point — there is not a single song on here I’d be embarrassed about

being caught listening to, regardless of whether it’s a cover or an original.

The album’s only flaw is that it is hopelessly stuck in the summer of 1964,

rather than in the fall of 1965, in between which lies a distance of

"two thousand light years from home". But since we are now almost

equidistant from both, why can’t we just pretend that it’s a 1964 record and

get away with it? Especially since it’s not trying to «emulate» 1964, it just

lives and breathes 1964.

Or maybe make it 1959, as the LP opens with quite a

fabulous cover of Fats Domino’s ‘I’m Ready’ — a song that, for some reason,

had never been picked up by anybody since its original single release. It’s

one of my favorite Fats tunes, and the Searchers do it almost perfect British

Invasion justice, apart from a somewhat clumsy guitar solo by Pender,

starting out strong with Berry-style trills and everything but then kind of

coming apart at the seams. Tony Hatch (their producer) is at the piano

himself, banging out a good Fats imitation, and Chris Curtis puts together

enough breath control to make us believe that he is indeed "ready",

"willin’", and "able". None of this suffices to make you

forget Fats’ original, but it does lend credence to the idea that of all the

different types of rock’n’roll music, New Orleanian rock’n’roll was the one

that somehow came most naturally to this particular band.

Right after that, the Searchers come out with

another note-perfect cover — of Marvin Gaye’s ‘I’ll Be Doggone’, and

before you start wondering how on earth would they succeed in challenging the

magic of Motown, I’d like to remark that the song, written by Smokey Robinson

and several other Miracles, was actually founded on a riff nicked directly from the Searchers’ own

‘Needles And Pins’ (well, more correctly, Jackie DeShannon’s ‘Needles And

Pins’, but it’s more likely that Smokey himself heard it from the Searchers’

hit version); so, in a way, they were paying Motown back here for stealing

what was theirs in the first place. In essence, ‘I’ll Be Doggone’ is a

folk-pop song, and the Searchers’ version exploits that essence a bit better

— although, of course, outsinging Marvin is a far more challenging matter

than outplaying his backing band. They do have the added benefit of group

harmonies, rounding out the elegant effect of this semi-romantic,

semi-threatening little mood-swingin’ serenade. (I refuse to fight over which

of the two versions is better, but taken together, they definitely beat the

stuffing over the popular Tages cover from 1966

— kudos to the Swedish lads for trying to turn the song over on its head and

transform it into an angry blues-rock rant, but it was never intended to be

that and they can’t tame it).

Of the cover songs that everybody usually knows, really

the only blatant misfire is the band’s take on the Ronettes’ ‘Be My Baby’ —

just because it is so utterly, perfectly pointless. They try as hard as

possible to preserve the oceanic production depth of Phil Spector, but it’s

clear as day that the best they can offer is an approximation, and who the

heck needs an approximation of perfection? Besides, the bombastic production

requires vocals that will cut through it like broken glass — something that

Ronnie Spector was able to provide, unlike poor Frank Allen, whose lead vocal

here sounds like it’s coming from the bottom of a well. Perhaps if they’d

rearranged the song as a cozy, intimate folk-pop recording, the results might

at least be interesting, but instead it’s just a tentative answer to the

question, «can a band of four guitar-totin’ British kids replace Phil

Spector, Ronnie Spector, the entire Wrecking Crew, and a full-blown orchestra

to the exact same effect?» And I’m not even sure I want to wait for an answer

to that question, provided that I respect The Searchers as one of the best

bands of the early British Invasion era and not as a bunch of before-their-time

contestants for Britain’s Got Talent.

Of the lesser known covers, though, one might single

out the band’s comparatively more interesting take on ‘You Can’t Lie To A

Liar’, a song that certain broken Internet algorithms, amusingly, ascribe to

the pens of Disney songsmith Frank Churchill and jazz vibraphone genius

Lionel Hampton (!!) — don’t put your trust in Wikipedia, because the song was

actually written by Bacharach-David disciple Paul Hampton, sometimes (but not on the original record)

co-credited with Texan singer Cinthy Churchill. (On the Searchers’ LP, the

credits just go «Hampton, Churchill» and then digital idiocy takes over from

there). This one was originally recorded by Ketty Lester, the

one-hit wonder of ‘Love Letters’ fame, as a sharp-edged country-western

number with prominent fiddle, which contrasted intriguingly with her

typically African-American R&B voice, and although it was later covered

by the likes of Bobby Vee and others, the Searchers model their version after

the original, but replace the fiddle with fuzz guitar, throw in more of those

booming ‘Be My Baby’-like drums and borrow the New Orleanian rhythm of Fats

Domino’s ‘I’m In Love Again’ (it was not so prominent on the original). If

only they could get Ketty Lester to actually sing on the song... everything

is good, but the soul just so happens to be missing. It’s a song that needs a

passionate solo delivery, not timid double-tracked vocalizing.

An unquestionable

win for the Searchers in all respects is Jackie DeShannon’s ‘Each Time’ —

this song of hers was first released by the minor U.S. girl group The Bon Bons in 1964

as, well, a typical girl group song with a corny-syrupy approach to the

vocals. The Searchers turned it into a sparkling guitar-fest instead (the

arpeggiated trills of the rhythm guitar and the harpsichord-style overlays of

the lead guitar are a complete reinvention of the original), and the vocals

melted down all the syrup and turned the song into deep-reaching dream-pop,

finishing each chorus with a head-spinning falsetto twist. Just compare the

way the Bon Bons sing "...EACH

TAAA-IIIM!" with the heights to which the Searchers take that

resolution, and then I dare anybody insist that Pender, Curtis, and co. had

but a mediocre ear for melody and harmony. It is just surprising to me that

with such a beautiful gift for taking a C-level song and elevating it to at

least a B+, if not higher, they kept smashing their heads against songs like

‘Be My Baby’, trying to out-perfect perfection. Surely there must have been dozens more of those tunes like ‘You

Can’t Lie’ or ‘Each Time’ that they could have successfully made their own.

Or, perhaps, they could have simply written more on

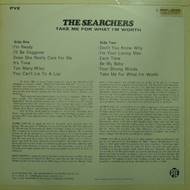

their own, because the four originals included on Take Me For What I’m Worth are quite sympathetic as well. John

McNally contributes ‘It’s Time’, which shows he must have been listening to

the Byrds’ debut — same kind of catchy, fast-paced folk-rock, and there’s not

even any shame in ripping them off given how much the Byrds must have been influenced

by the Searchers themselves. His ‘Don’t You Know Why’ is a bit more traditional,

echoing the classic Merseybeat sound, but I think the song might have fared

better if they donated it to the Hollies, who would have polished and

sharpened both the guitar sound and the relatively limp vocals. Meanwhile, Pender

and Curtis make a dubious, but not senseless stab at marrying pop harmonies

to the Bo Diddley beat on ‘I’m Your Loving Man’ (not a highlight) — and then

come up with one of their very best folk-pop originals with ‘Too Many Miles’,

a graceful and super-catchy pastoral ballad with a quasi-baroque woodwind

lead part. I have no idea why the song has been so completely forgotten (it

was actually the B-side to the ‘Take Me For What I’m Worth’ single, so it had

a real chance of getting some airwaves), but I think it belongs on any solid

compilation of early Sixties’ stately ’n’ sentimental folk-pop à la

Peter, Paul & Mary or Ian & Sylvia (whose own ‘Four Strong Winds’, by

the way, is also here).

The fact remains that Take Me For What I’m Worth by no means sounds like a genuine swan

song — despite their commercial struggles and lineup perturbances, the

Searchers remained an inspired and creative outfit all through 1965. But they

were unwilling to move forward at

the same pace as everybody else, preferring to take it slow and sensible

instead. We see faint glimmers of baroque-pop, we hear occasional outbursts

of fuzz guitar, we sense that they were not stubbornly committed to forever adhering

to the standards of 1963–64, but, unfortunately, this kind of pussyfooting

was not enough for such a vibrant era as 1965–66. Personally, I would be

interested in hearing a Searchers’ LP from the psychedelic era but, judging

from the small bunch of singles they would put out in those years, they would probably not be too

interested in recording anything too

psychedelic or too «artsy» — and it

wasn’t even so much about the departure of their informal band leader, Chris

Curtis, in April ’66, as it was about the overall group spirit and its

refusal to adapt at the required insane tempo of change. If you want me, you’ll take me for what I’m worth — this kind of

bluff may have worked out fine for Bob Dylan, but the Searchers really

overestimated their chances with this one. But make no mistake about it, on my lips there’s definitely a sweet

word and not a curse when I listen to all these nice songs sixty years later.

|

![]()