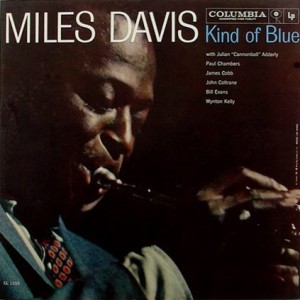

Miles Davis

Miles Davis

| Release date | Label | Producer | Genre | Length | More info |

| 1959.08.17 | Columbia | Teo Macero/Irving Townshend | Modal Jazz | 45:51 |

|

Modal jazz is like modal logic: you might love it... but it is absolutely not necessary that you do.

Background

The first thing that the layman is always taught about Kind Of Blue is that "modal jazz begins here", which sounds fairly important, except that a true layman will have a hard time understanding the real big difference between "chord-based" and "mode-based" playing - not to mention having an even harder time understanding why it is the "mode-based" jazz record that just has to be considered the quintessential and most important jazz album of all time, rather than any select "chord-based" one. It will be even harder to understand once you learn that for Miles himself, Kind Of Blue was more or less a one-time experiment. It was neither his completely first foray into the limitless possibilities of modal jazz (that is usually acknowledged to have been the title track on the earlier Milestones), nor his last, but it was pretty much the only record in his catalog that espoused modal jazz as a central ideology - and later on in his life, he would even brush it off as just a phase, one that came and went like so many others. Judging Miles Davis by Kind Of Blue is really like judging Captain Beefheart by Trout Mask Replica: it is kinda inevitable, but it grossly skews and distorts the overall picture of both the artist and the genre that he represents.

Nevertheless, jazz music was on the verge of not even one, but several concurrent revolutions in the late Fifties, and it is funny that Miles, already a well-established pro and one of the progenitors of "cool jazz" in the late Fourties, was breaking down conventions in his own way at exactly the same time as the much younger Ornette Coleman. Compared to Shape Of Jazz To Come, released the same year, Kind Of Blue gives the impression of being fairly timid and conservative in comparison - an aural illusion, perhaps, but a forgivable one, because, unlike Coleman, Miles liked to defy convention in ways that could be smooth and acceptable for the "common ear": for that jazz era, Miles was its Beatles where Coleman was its Velvet Underground (and the Kind Of Blue / Shape Of Jazz To Come opposition, in quite a few ways, could be said to have later been reflected in Sgt. Pepper vs. The Velvet Underground & Nico). In between the two of them, they turned jazz, for a brief while, into the hippest music for young shade-wearing European intellectuals, priding themselves on getting the strange new vibes of a brand new era that singled them out from their Duke Ellington-happy parents (a trend that had already started with bebop and Charlie Parker, but arguably only reached its apogee a decade later); and it is also, perhaps, not a coincidence that 1959 was also the year in which the original wave of rock'n'roll seemed to have run out of fire, so that "rebels" around the world could so conveniently switch to the new sounds in jazz, a musical genre that could be felt to wane a little around the middle of the decade but then kicked in with such a surprising vengeance at its end.

Some basic factsThe tracks were cut in just two days (March 2 and April 22, 1959) at Columbia's 30th Street Studio and allegedly involved very little preparation: Miles came in with the basic themes conceived as melodic sketches, gave a few cues, and had the band rolling - in fact, ʻFlamenco Sketchesʼ does not even have a particular theme as such. Expanded re-issues of the album confirm that ʻFlamenco Sketchesʼ was, in fact, the only number that yielded at least two complete takes: everything else was played in bits and pieces before the one and only complete take would be cut. Not that this approach is such a particular rarity for jazz, but it does stupefy the mind a bit when you remember we are talking about the most treasured jazz album of all time (from this "spontaneity-based" point of view, the only analogy in rock music would be some of Dylan's classic albums).

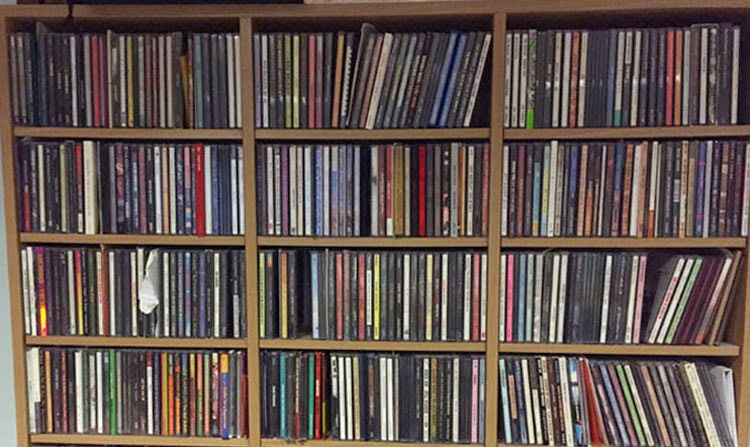

The most amazing fact about the Kind Of Blue legend, probably, is that it would go on to become the best-selling jazz album of all time, quantified as "4x platinum" where its nearest competition, much later fusion stuff by Herbie Hancock and Weather Report, would only reach single platinum status. The most logical (and only) explanation for this is the "That shelf sure looks unintelligent without a jazz album on it, which one should I buy?" question, much like the one that is also asked in relation to classical music and usually results in the addition of Gould's Goldberg Variations to one's collection; I'd guess that the number of people in this world who own Kind Of Blue and "get it" (or at least listen to it on a regular basis) is probably four times the number of people who really have a right to call themselves jazz lovers. Hence, my first advice - if you know nothing/little about jazz as a genre, but want to "get" it, don't start with Kind Of Blue, it'll probably just mess you up. Start with Louis, or the Duke, or even Brubeck, or if you insist on Miles, start getting into him in chronological order - at least listen to Birth Of The Cool and 'Round About Midnight before Kind Of Blue, not after it, to be able to put it in the proper perspective. This is one of those cases where "best-of" lists really don't help.

For the

defense

One thing that I will not even try to do is "defend" Kind Of Blue based on formal musicological arguments. Not only do I not have the slightest amount of qualification to do that, but there's like a million printed sources that analyze its five tunes right to the bone, and anyway, it is not going to do me or most other people that much good to learn that ʻBlue In Greenʼ mixes dorian, mixolydian, and lydian modes if, for instance, we lack the ability to relate the shuffling of these three modes to the shuffling of three different moods. Essentially, the transition to "modal" form is viewed as a way to broaden the possibilities of the players, enabling them to move in an almost limitless number of directions even while relying on fewer chords than usual. The real question, however, is - does one actually feel that freedom? Can you listen to Kind Of Blue and exclaim, "Man, those guys can really do anything now!"?.. That's quite a hard one.

First, though, a few words about the main themes - the "least free" pieces of the puzzle. The biggest problem of jazz for "non-jazzers" like me is memorability (often equaling "complete inability not only to keep a particular track in memory, but even to distinguish it from its surroundings"), and on that count, I am glad to say that Kind Of Blue behaves much better than the average jazz album (at least after half a dozen listens). Two of the tunes, ʻBlue In Greenʼ and ʻFlamenco Sketchesʼ, are ballads, not even meant to have a specific central hook (although some of Evans' piano phrasing on ʻBlue In Greenʼ could probably qualify); the other three do have nicely written themes that can be imprinted in memory very quickly. ʻSo Whatʼ is particularly good - its call-and-answer structure, where Chambers "makes an important statement" on his double bass and the piano or the trumpet or both answer "So what?", is a delicious bit of enigma. Next to it, ʻFreddie Freeloaderʼ at first feels underwhelming, especially because its "hook" is also based on a similar two-note brass call (in fact, first time I listened to this album without paying attention, I ended up missing the transition between the two tracks altogether!), but soon enough, its simple blues theme becomes friendly and hummable. And the nervous piano vamp that appears at the beginning of ʻAll Bluesʼ makes a great transition into the almost "James Bondian" little brass bit at 0:42 into the track. (By the way, the understanding that ʻAll Bluesʼ and ʻFlamenco Sketchesʼ were probably incorrectly switched places in the track listing feels right to me - ʻAll Bluesʼ definitely has more of a flamenco feel to it than what is actually called ʻFlamenco Sketchesʼ).

That said, the "meat" of the album is not in its themes, but in the trumpet / tenor sax / alto sax improvisation that goes in between, as the themes just set a mood and then allow the musicians to go anywhere they want as long as they do not mess up the tempo. With Evans (or Kelly) rarely taking solos at all, this is essentially a series of contests between the three blowers, and this is frankly just impossible to properly appreciate outside of context. Describing what it is that makes these solos different from the ones on, say, 'Round About Midnight, in "layman" terms is impossible. After a few comparative listens, you might begin getting the feeling that the musicians on Kind Of Blue are much less tied to the songs' general structures, finding themselves in a state of free flight most of the time, although this is arguably more true of the "energetic" numbers than it is of the ballads, where they seem to be engaging in a much more traditional form of "nocturnal" lounge jazz solos - melancholic on ʻBlue In Greenʼ, romantic on ʻFlamenco Sketchesʼ (or is that ʻAll Bluesʼ).

The best type of improvisation is one that somehow "tells a story", with its own expositions, developments, and culminations; repeated listens will probably lead to your establishment of all these, but for now, I just kind of like the sequencing of the "holy trinity", such as on ʻFreddieʼ, where the "Miles-voice" serves as the relatively calm exposition, the "'Trane-voice" takes things to a slightly more nervous and agitated level, and then the "Adderley-voice" acts as a slightly more sensible and rational companion to the tenor sax. (On ʻAll Bluesʼ, they revert the sequence, so that the calmer Adderley comes first and the agitated Coltrane comes next). The important thing here is that the solos are the music, not just obligatory conventions based around the chord structure, and all the soloists understand that, trying to invent and create rather than rely on stock phrasing. However, feeling that, and, more importantly, feeling that this is being done with more inspiration than it would be done by your local jazz bands in your local jazz clubs, may be difficult.

For the prosecution

As banal as that may sound, I do have to say that an album that is almost completely based on improvisation can hardly qualify for "best album of all time in genre so-and-so", regardless of how important the concept of improvisation is for the genre. Most of the themes on Kind Of Blue, with the exception of the simple genius of ʻSo Whatʼ, can hardly even qualify as the best themes written by Miles; and as great as the players are, the particular greatness of Kind Of Blue is really more due to its theoretical breakthroughs than to any particular emotional resonance encapsulated in these compositions (and no others). I can feel how it is altogether different from Milestones; I cannot quite feel that it truly elevates me to a different plane of consciousness.

Ultimately, it all boils down to whether you find all the soloing here "breathtaking" (closer to the conventional view) or just "pretty" (closer to mine). Ido have to confess that I find lengthy solos on wind instruments generally "background-ish" in nature, unless they try to conform to some sort of catchy pattern, and that Bill Evans should have had more space to himself (he usually either gets no solo at all or his is the shortest one). I do also have to confess that, for all of the record's reliance on "mode-shifting", it mainly relies on just three moods ("cool" on ʻSo Whatʼ and ʻFreddieʼ, "agitated" on ʻAll Bluesʼ and "sentimental" on the two ballads), and that mood shifts between the soloists are too subtle to make a hell of a difference. For an album that is supposed to act as the novice's introduction to jazz, this is... well, no Sgt. Pepper, that's for sure. Is that a problem? I think that is a problem. Maybe too obvious a problem, but sometimes it makes sense to restate the obvious.

Conclusion

| Melody | Voice | Mood | Production | Innovation/Influence | Where it belongs | RYM preference | |

|

× |

|

|

|

|

#11 (Mar 13, 2016) |

| Previous entry | Main page | Next entry |