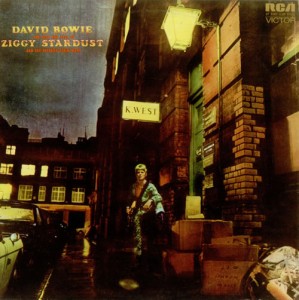

David Bowie

David Bowie

| Release date | Label | Producer | Genre | Length | More info |

| 1972.06.06 | RCA | David Bowie / Ken Scott | Glam Rock | 38:28 |

|

Psychoglam Hamlet for 12-year olds of all ages.

Background

It was always a little bit of a puzzle to me why such an obviously talented guy like Bowie had to struggle all the way through the Sixties - "Davie Jones"' first single came out as early as 1964 - completely overshadowed by his superiors, only to stage a meteoric rise to superfame over a brief period of about two years, 1971-72, an age in which competition may have been even harsher than in the mid-to-late Sixties. Of course, Bowie was seven years younger than Lennon, and you could discount a large part of that Sixties period as his "Hamburg" stage, but still, his "chameleonic" instincts were perfectly visible already back then, as he quickly and easily mutated from lusty blues-rocker to gentlemanly Brit-popper to psychedelic acoustic troubadour... and apart from the popularity of ʻSpace Oddityʼ, which may have very well remained an exception and locked him in the annals as a one-hit wonder, never got anywhere much with all those efforts.

The thing is, Bowie had always been a strategist by nature, an artist with an instinctive knack for pre-guessing public taste and giving the public precisely what it wanted at the right moment. Unlike one's natural gift for songwriting, though, which may be made manifest at any age, this strategical instinct had to be nurtured. Most of the Sixties he spent jumping on other people's bandwagons - blues-rock a la Stones, Brit-pop a la Kinks, acoustic psychedelia a la Donovan and Tyrannosaurus Rex; regardless of how fine the songs were (and some of them were fine all right: there are a few melodies on 1967's David Bowie that could rank along his best written classics), all that time was spent imitating rather than innovating.

So what exactly happened in 1971-72? Bowie's amazing jump into superstardom at the time could, of course, be simply ascribed to the grand spectacle: Bowie became one of the earliest and best propagators of "rock theatre", giving the era's novelty-craving kids an icon they couldn't refuse. But no amount of hair color or meticulously cultivated "androgyny" would have turned him into such a phenomenon if it weren't for the music, which goes along so naturally with the image anyway. Rock energy, pop hooks, and sci-fi thematics - the ultimate combination, and it was pretty much invented by Bowie. Well, one could argue that the whole concept was stolen from T. Rex, just as his earlier 1969 image also owed a lot to Marc Bolan's early career; and for a while, Bowie's and Bolan's popularity went pretty much hand in hand. Yet there's the issue of the fourth ingredient - "depth and complexity": unlike Bolan, Bowie made a gamble for eternity, by trying to write music that was not solely oriented at the current moment, and gained the winning hand: almost half a century since its release, Ziggy Stardust continues to be revered as one of rock music's finest statements, whereas Electric Warrior, at best, occupies a respectable place on the auxiliary shelf of the canon.

On the other hand, it is also clear enough that the "otherworldly" elements of Ziggy Stardust were the element that pushed the man in the stratosphere: Hunky Dory from the previous year, which did not begin rising up in the charts until its successor gave it a proper push, has plenty of rock energy, pop hooks, depth and complexity, and the only thing that it is really missing is a starman waiting in the sky (which is why, for a large number of "Bowie snobs", Hunky Dory is unquestionably the better album of the two, since it does not pander to the masses so brazenly). But you see, it takes quite a bit of talent to turn yourself into a revered icon for teenage kids - and it arguably takes several times as much talent to make a record that appeals to teenage kids and rock critic "intelligentsia" on an equal level, even if for slightly different reasons. In 1972, the concept of the "intellectual pop star", so to speak, was pretty much non-existent (not even Dylan in his thin mercury days was really a "pop star" in the most direct sense of the word) - someone had to invent it, and why should we be surprised that Mr. Bowie took on the opportunity?

Some basic factsSomewhat symbolically, perhaps, David is not sporting the iconic "Ziggy" look on the album photo - probably because it was not invented or at least finalized at the time; one could, in fact, argue that Bowie's default "glam era album" would really be Aladdin Sane (which did sport the Ziggy look!), and that Ziggy, in a way, is still a transitional album, on the way of transforming him from poppy singer-songwriter into weird alien rocker. On the other hand, the production of Ziggy, with its multiple overdubs, heavy guitars, echoes, astral effects, etc., is deliberately very different from the much more sparse and "homely" production of Hunky Dory, and probably contributed a lot to the record's chart success... which, by the way, wasn't really that huge: in the UK, the album only made it all the way to #5, meaning that more people probably heard of David Bowie at the time than actually heard, or at least bought, the music. It would take yet another decade for David to achieve his biggest commercial success, with Let's Dance - a record that sold far more copies, but could never even begin to wish for such a legendary status as the Ziggy project.

Anyone seriously interested in the "non-Ziggy" side of Ziggy should probably invest in the 2002 30th Anniversary edition of the record, which throws on a number of underproduced acoustic demos, alternate mixes, and various other songs recorded in 1971, including Jacques Brel's ʻAmsterdamʼ and Chuck Berry's ʻRound And Roundʼ. Most of them ended up not being on Ziggy for a good reason, but they place it in some classy context. Really, you don't need to hear David Bowie doing Jacques Brel or Chuck Berry, because these guys are more or less self-sufficient; but without Jacques Brel, there would be no ʻRock'n'Roll Suicideʼ, and without Chuck Berry, there'd be no ʻSuffragette Cityʼ, so...

For the

defense

Like so many rock classics, Ziggy Stardust is designed for at least three stages of perception. On the most superficial ("teenage") level, this is a romantic musical story about an alien guitar-playing superhero - a sci-fi tale that easily captures the immature imagination and satisfies its yearn for escapism. Later on, you may come to understand and reject its cheap thrills as a product of corny, easily decipherable manipulation. But as time goes by, the songs may take on an entirely new life, and this is where the talent (I am hesitating to say "genius", a term I've never felt appropriate for Bowie in general) really shows through. Yes, the songs were carefully crafted to blow the minds of a newly reared generation of British teenagers: to them, Ziggy Stardust in 1972 was what Hard Day's Night was to their elder siblings in 1964. But as I relisten to them now, about a month after ol' Ziggy himself finally joined his Spiders in the sky (at this moment, by the way, only the drummer is still alive), I am amazed how fresh, relevant, intelligent, and even emotionally moving most of this stuff continues to be.

For starters, ʻFive Yearsʼ, as long as its scenario is not taken completely literally, is one of the apocalyptic greats - more music hall than rock'n'roll, perhaps, but also clearly inspired by Brel and other French people, is Bowie at his acting peak. No verse-chorus structure here, just a slow, steady, perfectly planned build-up through a series of crazy lyrical images, the singer gradually whipping himself into a frenzy before finally exploding - even when I'm in a good mood, ʻFive Yearsʼ never fails to remind me of how shitty things really are, and how much shittier they are going to be in one year, never mind five... good, good job, Mr. Bowie. Should I be ashamed of probably having the same sentiments here as a 12-year old boy or girl in 1972, aligning his/her hormonal rebellious streak with the tragic-romantic aura of the song? Nope. It works for 30-, 40-, 50-year olds just as well.

Or take the central song on the album, ʻMoonage Daydreamʼ. The flashy power chords, the multi-tracked scraping guitars, the shrill echoey voice of the singer, the orchestration, the lyrics, and, of course, Mick Ronson's solo - all of this combined to create the perfect teenage mindblower, a song that, when performed in concert, really made the kids go crazy (as you can witness yourself in the Ziggy Stardust movie). But it blows my mind even now, not as a musical presentation of some supernatural being, but as a marvelous allegory for what it really is to be "overpowered": the song almost chokes on its own cockiness, and yet, at the same time, has a tragic underpinning from the very first seconds: Bowie's "I'm an alligator, I'm a mama-papa coming for you" is sung with almost desperate overtones (something a Marc Bolan would never allow himself, for instance), showing how the protagonist, despite all his superhuman nature, is really just a helpless tool of fortune. The incitement to "freak out in a moonage daydream oh yeah" is not an appeal to have fun and be happy - the singer is inviting his audience to go down with him in flames, really, and then Mick Ronson comes along and ignites the flames, with a guitar solo that is stunningly stupidly primitive and totally wholesomely awesome at the same time, a solo that matches the ambiguity of the singer to perfection - it's wild, spaced out, unbridled, but it has a suicidal aura around it, especially when Mick begins shooting those crazy laser beams in space around the 3:30 mark. That is probably the single best glam rock solo in the world, capturing all the superficiality and all the possible depth of the genre.

Maybe, I thought, I would not be able to hear ʻStarmanʼ without grinning after all these years. After all, let's face it, ʻStarmanʼ is somewhat of a ʻYellow Submarineʼ in Bowie's catalog - a song so audaciously childish, with its la-la-las and "let all the children boogie" and almost Sesame Street-style chorus melody (still one of the catchiest in Bowie's entire catalog, though), it just can't seriously hold up. But somehow it does, at least in the context of the album where it actually works as a timely antidote against the psychedelic overdose of ʻMoonage Daydreamʼ, calming you down and blowing up excessive seriousness - as the chorus goes up, up, up with warnings of the mysterious Starman who's ready to "blow our minds", you almost expect another acid epiphany, but what it breaks down to is just... "let all the children boogie". And a bunch of la-la-la's. Anti-climactic? Sure. But we needed that, just to remind ourselves that rock'n'roll suicide is not the only solution.

And who really remembers now, without googling it up, that ʻLady Stardustʼ was originally dedicated to Marc Bolan? It works perfectly fine without any specific references, an Elton John-style piano ballad about a rock star and his relations with the opposite sex. What matters is not what is being sung, but how it is being sung - again, with a deep sense of some dark unnamed personal tragedy underlying every note; the sustained falsetto "cliffhanger" of the "really quite paradise..." line is never really properly resolved, as if the narrator is reluctant to finish the story and, sparing our senses, just reverts to the more calm and common "and he sang all night long...". For those who are willing to take it, there's quite a bit of gripping psychologism going on here.

Maybe the rock'n'roll stuff has dated? Well, I don't know, ʻSuffragette Cityʼ still sounds outta sight, she's all right to my ears. Nobody can really guess what the lyrics mean, but most likely, the song has something to do with the wild freedom that people allow themselves over the pre-apocalyptic five year period (and it does mention "droogie", a clear reference to Clockwork Orange), and the melody follows suit, with a wild one-note piano line that's equal times Little Richard and John Cale and a perfect encapsulation of the "glam" take on rock'n'roll (distorted guitar, yes, but obligatorily mashed with pianos and horns for thickness). Its "wham bam thank you ma'am!" is a direct reflection of "five years, that's all we got", and the song should, in fact, qualify as the official grandfather of all those Eighties' hair metal anthems that were smart enough to take themselves with a grain of salt and irony - hedonism laughing at itself. Not a lot of proper rock'n'roll excitement, it's too self-consciously smart for that; but quite a bit of vitriolic bile, which compensates fair enough for the lack of kick-ass riffage or balls-out soloing. And if you want rock'n'roll excitement, you'd better ʻHang On To Yourselfʼ - the Ramones did not rip off its main riff for ʻI Don't Wanna Go Down To The Basementʼ for nothing, after all.

In short, Ziggy still cuts a respectable figure, both in terms of individual songs (many, if not most of them, have really solid hooks, vocal at least, and sometimes instrumental as well - on the whole, it is probably the catchiest of all Bowie records) and in terms of the concept, because all these visions of stardom, freaking out, excess, self-destruction, apocalypse, futile or not-so-futile attempts to prevent it, etc... well, we may not be 12-year old kids any more, but the relevance of it all has never truly gone away. For what it's worth, nobody ever since - not one artist, not anywhere in the world that I know of, at least - has really produced a song that would render ʻMoonage Daydreamʼ superfluous. It may not be the most psychedelic song in the universe, of course, but it is probably the best psychedelic song in the universe to be played at one's funeral, and that's gotta count for something.

For the prosecution

Well, obviously, the entire concept of Ziggy, if you take it too literally, is silly - as is the concept of Tommy, and SF Sorrow, and whatever other concepts we had in rock's golden era. Honestly, nobody except for biographers need really bother with Bowie's confused and confusing explanations of the actual "storyline" behind the music, which did not really matter then and certainly does not matter now. This, by the way, is why I was never a fan of the title track: it may feature the single most memorable riff on the record, but, unfortunately, it is largely misused for a boring "retelling" of the Ziggy myth, way too literal in comparison with every other song on the album.

Many of the individual songs have their smaller or larger flaws, too. ʻIt Ain't Easyʼ is not bad, but I always keep thinking that, true to its recording dates, that one should really have ended up on Hunky Dory, whose atmosphere the acoustic verses share far more loyally than the outta-sight atmosphere of Ziggy. ʻSoul Loveʼ is decent, but has the misfortune of being placed right before ʻMoonage Daydreamʼ - which is somewhat similar in terms of music, but chews the former up and spits it out in a jiffy. And there may be just a trifle too many songs that have the word "star" in the title, don't you think? Again, ʻStarʼ proper is an okay rock'n'roll number, but as a rock'n'roll number, it is destroyed by ʻSuffragette Cityʼ.

Anyway, as far as my own tastes and feelings are concerned, Bowie never made a completely perfect album - something reserved for musical geniuses, which, as I already said, is a term I refuse to apply to Mr. Davy Jones. Even on this record, one of his most overtly commercial ever (and even specifically oriented at a younger audience), some of the tracks are too "conceptually driven" and place more emphasis on words than music. But if that is what he thought necessary for this particular event - fine by me. After all, a few subpar numbers only help to bring out the best in the classics, don't they?

Conclusion

...and if you think I'm being way too serious here, then how about this: Ziggy Stardust simply blows the mind and kicks butt at the same time, from beginning to end. Most of Bowie's other albums either blow the mind or kick butt. This one does both. Honestly.

| Melody | Voice | Mood | Production | Innovation/Influence | Where it belongs | RYM preference | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

#12 (Mar 20, 2016) |

| Previous entry | Main page | Next entry |