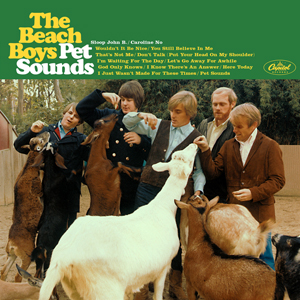

The Beach Boys

The Beach Boys

| Release date | Label | Producer | Genre | Length | More info |

| 1966.05.16 | Capitol | Brian Wilson | Classic Art Pop | 35:52 |

|

The ultimate in elegiac zoophilia: a teenage symphony to Goat!

Background

The Beach Boys' evolution in the Sixties is conventionally compared to that of the Beatles - the Great Trans-Atlantic Battle of the Decade - but on the grand scale of general popularity the battle is fairly hopeless for the Wilson brothers, and it is usually only when one becomes deeply engrossed in the intricacies of pop/rock music evolution that the genius of Brian Wilson starts getting equal respect with the double-headed genius of Lennon/McCartney. For some reason, even though both the Beatles and the Beach Boys started out having young excitable girls as their core audience, and even if in terms of "spiritual depth" A Hard Day's Night is hardly that much superior to All Summer Long (well, I guess the word "hard" sounds spiritually deeper than the word "summer"), the Beatles found it that much easier to drop off the adolescent baggage than the Beach Boys - you can blame it on the cheapness of the American PR machine versus the British one, or you can blame it on Mike Love and his eternal surf drive, but the fact remains that artistic pressure on the Beach Boys was always harsher; and even today, for oh so many people The Beach Boys = "I wish they all could be California girls" rather than "God only knows what I'd be without you".

To me, it always made sense to actually separate "Brian Wilson" from "The Beach Boys" - the two entities were obviously related, starting out together, then splitting from one another and entering in a long, complicated, sometimes fortuitous, sometimes detrimental symbiotic relationship. Essentially, the split was formalized in January '65, with Brian's decision to refrain from touring (more than a year and a half before the Beatles followed suit), and for what it's worth, Pet Sounds is not really a "Beach Boys" album, but a bona fide "Brian Wilson" album, featuring the Beach Boys as guest stars providing vocal harmonies and one guest tune (ʻSloop John B.ʼ definitely has the classic "Beach Boys" vibe). What this does is help understand perhaps the most groundbreaking thing about the record - which is not in its unorthodox handling of harmonies, tonalities, instrumentation, etc., but in its singer-songwriter-ish psychologism. Many people were already busy at the time working on the whole "baroque pop" thing, but Pet Sounds is arguably the first genuinely "autobiographical-confessional" record in pop history, an honest musical self-portrait of a deeply sensitive, vulnerable, emotional human being that had absolutely no precedent to it - neither the Beatles, nor Dylan with his masques and veils, nor anybody else had tried anything like that before on such a massive scale (although individual songs could qualify, of course). If we cast the net even wider, we'd have to root for people like Sinatra or Billie Holiday - but those guys were interpreters, not writers, and poured their souls into other people's vessels; Pet Sounds, being under Brian's complete control, provides both the soul and the vessel.

Consequently, the endless Pet Sounds/Revolver or Pet Sounds/Sgt. Pepper comparisons totally miss the mark, because we speak of incomparable entities. Could one seriously state that a song like ʻShe Said She Saidʼ is "better" or "worse" than anything on Pet Sounds? We might as well extend the comparison to a pot of lobster bisque. While the simple fact of Brian Wilson being competitive and genuinely wishing to make his own mark on the world of music that could be as strongly and widely admired as that of the Beatles is undeniable, he never made the mistake of betraying his inner genius, and trying to go in some direction in which he would be inefficient, such as hard rock or acid psychedelia. Instead, he created a trampoline all his own, which would later be used by Love (Forever Changes), the Zombies (Odessey & Oracle), Nick Drake, Tim Buckley, Joni Mitchell, and just about any "singer-songwriter" with a confessional/introspective rather than commercial angle. Of course, "The Beach Boys" helped a lot - had "Brian Wilson" simply been a genius loner, he would not have the necessary means to produce a record like Pet Sounds: the surf-car-girl hits he wrote for the band in 1962-65 earned him the right to make Pet Sounds just as effectively as the same "Beach Boys" would later drag him down. All in all, the entire story of Pet Sounds is one fascinating study of causes and effects, intersecting factors, and historical accidents.

Some basic factsOf the more than 60 (!) musicians contributing to the sessions, arguably the most important ones to deserve special mention are "Wrecking Crew" members Carol Kaye (bass guitar); the ever-present Hal Blaine (drums); Glen Campbell and Barney Kessel (guitar); Larry Knechtel (organ); and Steve Douglas (winds), though there could probably be a whole book written to cover the pedigrees and relative roles of all the people involved in the recording. It should be noted that most of them had backgrounds in jazz, folk, classical, or country (not that a "background in rock" would be respectable or even possible for a professional session musician in 1966), which were dutifully noted and intelligently exploited by Brian throughout the sessions, resulting in a sound that was "soft" and even "housewife-friendly", in some ways, but could not be properly pigeonholed into any pre-existing genre.

Initial sales for the album were quite telling - #10 in the US (as compared to the silly Party!'s astounding #6), but #2 in the UK, their highest charting across the Atlantic so far; apparently, there was something distinctly "European" about the album (its "baroque" sheen?) that was simultaneously appealing to British people and confusing to Americans. Same business with the singles: ʻCaroline, Noʼ came first, carefully (and accurately) credited to "Brian Wilson" rather than "The Beach Boys", and only reached #32, whereas the upbeat ʻSloop John B.ʼ fared much better (#3). One shouldn't be too cross with the American public: Pet Sounds was not simply "unusual", but it was so completely different from what they'd come to expect from the Beach Boys that confusion was totally inevitable - remember that even the Beatles evolved at smoother rates in between each of their records, gradually accustoming their clientele to new types of sounds and moods. (Not that Wilson's evolution was not gradual - the entire second side of Today!, replete with gorgeous ballads, is well-known as a direct musical and spiritual predecessor to Pet Sounds, but still, it is way close to Phil Spector's style to have been that much of a shock to listeners).

On the whole, this large gap between critical admiration and public love continues to exist even today, but over the years, as the Beach Boys got less and less relevant as a hit-making machine, the gap was effectively narrowed, and today Pet Sounds finds itself in the happy group of forever-gold-standard pieces whose reputation is virtually unassailable. Naturally, this also led to numerous re-releases and expanded editions, way too many to mention them all: the hardcore fan will, of course, accept nothing less than The Pet Sounds Sessions, one of the earliest (1997) boxsets, I believe, to be dedicated to a single album - a stereo mix, a mono mix, and almost 3 discs' worth of demos, alternate takes, a cappella recordings, and studio chat. The not-so-hardcore fan, though, might remain content with the early CD release that added but three bonus tracks, one of them an early version of ʻI Know There's An Answerʼ, tellingly titled ʻHang On To Your Egoʼ - which might just as well have been an appropriate (if a little over-cocky) title for the entire record.

For the

defense

The most obvious superficial weakness of Pet Sounds is "monotony" - most of its songs are quite similar in terms of generated mood, relying on similar instrumental cocktails, similar slow tempos, similar harmonies, etc. However, once we have conceded that this turns Pet Sounds into a "niche" album, one that concentrates more on exploring the subtle nuances of one's soul rather than on trying to cover as much ground as possible (cue the senselessness of Beatles comparisons once again), the alleged "monotony" becomes more of an asset than a flaw: all you have to do is get in the mood, and then each single song will be revealed to uncover a single separate psychological aspect, some of which you are probably familiar with and some of which you may be happy to uncover for the first time, particularly if you're young and inexperienced.

Not coincidentally, each of the two sides of the album opens up on a deceptive note. ʻWouldn't It Be Niceʼ seems like a variation on the Ronettes' ʻSo Youngʼ, and lets us know that the album's core audience, according to Brian Wilson, still consists of romantic teenagers - "wouldn't it be nice if we were older, then we wouldn't have to wait so long" - and it's got one of the catchiest and cheerfullest vocal melodies on the entire record. But at least it is thematically coherent with the rest of the songs: ʻSloop John B.ʼ, which was not even one of Brian's original ideas (it was brought to his attention by Al Jardine, a big fan of the Kingston Trio), opens the second side as a merry sea shanty, hardly having anything to do with anything else. Their placement at the two tops is ideal: they lure you in with their catchiness and upbeat rhythms, and yet they do not break the flow of the record, having enough musical points of intersection with the other songs. This shows that when it came to finalizing the product, Brian was aware of the risks he was taking, and was sufficiently astute and flexible to "bait" the listener into the process... well, it didn't help with everybody, I guess.

So let us suppose that you are one of those who are still somewhat "bored" with the record, ready to acknowledge its formal beauty but not to be overwhelmed by its vibes. How would one go about making this transition? It's easy enough if you're 16-18 and you're in love, but then again, if you're 16-18 and you're in love, it's easy enough to be overwhelmed by just about anything. What is it that actually makes these Wilson songs so special, outside of their formal innovative aspects?

I would probably have to take "realism" for an answer. As has already been stated, this is one of the first, if not the first, true "singer-songwriter" record where honesty is key, and with the world of pop music oversaturated with all sorts of love songs, creating an album full of special love songs would only be possible if the songs in question strayed away from formula and wore their hearts on their sleeves - which is precisely what Brian is doing here. Listen to the string arrangements on any of these tunes: they are lovely, and yet so totally different from the regular orchestrations employed at the time for popular mini-serenades. Listen to... wait, here's just a small list of unusual stuff that totally makes sense:

- ʻYou Still Believe In Meʼ: the "resolution" of the chorus, which does not really sound like a proper resolution to my ears. The "how can it be... you still believe in me" bit - if you're like me, you'll find that "..still believe in me" not a fully resolved, conclusive finale, but more like an unfinished period. This adds a moment of doubt to the proceedings - or maybe a bit of surprise, making sure that this is indeed a question: how can you still believe in me, after all we've been through? In comparison to this, the prolonged "I wanna cry" is much more conclusive.

- ʻDon't Talkʼ: there's some goshdarn realistic magic here when Brian reaches the highest part of the verse ("...there are words we both could say...") and then swoops down in an almost dismissive way with "don't talk..." I keep thinking how a Sinatra might have handled this part, and I'm pretty sure he couldn't, he would probably consider it too crude for his taste. It's like a bitter diatribe against the power of words, with only the power of pure music being capable of coming close to matching true emotionality.

- ʻHere Todayʼ: apart from the song featuring four distinct vocal melodies, each one catchier than the previous, it's almost unusually cynical for this record: after all the chivalrous love declarations, to conclude that "she made me feel so bad" and that "love is here today and it's gone tomorrow"? And to conclude it in such a merry-go-round way?

Basically, the songs here cover and exhaust most of the possible issues with love relationships. There's youthful naivete (ʻWouldn't It Be Niceʼ), acceptance of love's necessity (ʻThat's Not Meʼ), chivalrous serenading (ʻGod Only Knowsʼ), religious repentance over one's infidelity (ʻYou Still Believe In Meʼ), and there's even space for some cliches like the "let me be your next boyfriend after your first one has dumped you" trick (ʻI'm Waiting For The Dayʼ , a song about which Brian himself later admitted that it wasn't quite up to par with the rest of 'em). Curiously, the song that sounds the closest here to a traditional "I love you yes I do", no perks added, is the instrumental ʻLet's Go Away For Awhileʼ - you could easily picture it in a Cinderella movie.

Anyway, I am not going to spend much time dwelling on the preciousness of individual songs or moments (I've written enough in my previous reviews): what I want to stress is that I actually admire how Brian Wilson, a fairly common, not-too-well-read American kid, came out with one of the most atypical love albums ever made. Every song here is "normal" (accessible), yet almost every song goes beyond "typical" love cliches, and not just because of a unique sense of melody or a novel way of utilizing studio possibilities - it's as if the guy was able to bring out the emotional content in his heart without mixing it up with secondary influences. In other words, it's all his. Could you hear a love song album in 2015 and go "wow, I could never imagine love themes being sung about in that way?" Probably not. By no means was Brian Wilson the greatest or the latest of all musical romanticists, but of all 24-year old American romanticists, he probably was the greatest.

For the prosecution

It is pretty much impossible for me here to come up with specific accusations against any particular tunes on the album. With Brian in absolute control, he was able to bring out the very best in everyone, Mike Love included, and although I do have personal favorites (such as ʻDon't Talkʼ), I don't have any serious grudges even against "lesser" material (I used to be a little miffed about the instrumental tracks, but the title track has seriously grown on me over the past decade). So the only real grudge that remains is... yes, that very same "monotony" that ultimately prevents me from spinning the disc too often - only when I'm in this particular mood, which probably depends on the moon phase or something.

Conclusion

| Melody | Voice | Mood | Production | Innovation/Influence | Where it belongs | RYM preference | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

#13 (Mar 27, 2016) |

| Previous entry | Main page | Next entry |