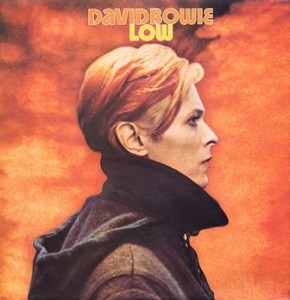

David Bowie

David Bowie

| Release date | Label | Producer | Genre | Length | More info |

| 1977.01.14 | RCA | David Bowie / Tony Visconti | Art Rock | 38:26 |

|

Sometimes all it takes for a musical revolution is one plane ticket from the West Coast to West Berlin.

Background

"Bowie Goes To Berlin" - the musical epic of the century. Conventional wisdom, more or less, has it as follows: In the early 1970s, while most of the world was going bonkers over glam, prog, singer-sonwriters, and other technological reworkings of the same old values of 1967, the stern and silent Germans were busy working on something completely different - pushing music in entirely new directions that had more to do with avantgarde, modern classical, and all the latest intellectual developments in music theory than with scoring hits on the commercial charts. And never the twain would meet, if not for Saint Bowie, who just so happened to be the first and best artist to merge the two worlds into one - a consummate hitmaker who, nevertheless, chose to plunge head first into the strange world of cold, robotic electronic bleeps and unusual chord progressions, eventually producing music that combined the essence of Krautrock and early electronica with a pop sensibility, and could be daringly innovative and commercially viable at the same time. In the process, he revolutionized the rock scene for a second time, and pretty much laid down the entire ground rules for all the New Wave, synth-pop, and "new school rock" to come.

This is, of course, a very crude simplification of the overall situation, and, most importantly, it goes without saying that New Wave and all those other things would have come on just as strong, and just as soon, even if Bowie had preferred to stay in Los Angeles and simply sink deeper into his cocaine addiction. As far as I'm concerned, it is not the fact that Bowie "revolutionized music" with The Berlin Trilogy that should be the most inspiring to us - it is the fact that for Bowie, personally, it was probably the most fundamental musical transformation of his life. While most of his peers either failed to recognize the tectonic changes that were going on in the mid-to-late Seventies as a whole, or invested in them sparingly and cautiously, retaining the tag of "classic rocker" for the rest of their lives, Bowie somehow managed not only to adopt the new paradigm wholesale, but to feel comfy and cozy in it: a 30-year old veteran rocker (and yes, the standards of 1977 still made little difference between rockers and porn stars when it came to age limits) who sounded just as adept at New Music as all the 18-year old kids who were relying on strange new sounds as their token to ward off stinking veterans and drive them into their early graves.

Basically, in 1972, David "Ziggy Stardust" Bowie, for all of his unusual artistic vision and musical qualification, was one of the leaders of the glam-rock pack, along with Elton John, Alice Cooper, Marc Bolan, and tons of lesser stars - people who were taking musical structures and values consecrated several years back, and coating them with operatic polish, visual imagery, and various personal artistic philosophies. Pretty much nobody from that crowd managed to survive the musical revolution of the mid-Seventies (sometimes literally survive, like Bolan): some could adapt a bit to new production values, some continued to have occasional hits, and some actually continued to make good music (even Elton's post-1976 catalog is not completely worthless, let alone Alice's), but Bowie was the only one who seems to have said to himself, at one point, "I will starve, I will crawl on all fours, I will skin myself alive, but I will never endure the dishonor of being called a rock'n'roll dinosaur" - and he kept that promise until the very end.

Some basic factsIt is interesting that, for such a groundbreaking record, the initial reaction seems to have been opposite to our retrospective expectations: critical reaction was fairly mixed, particularly because of the perceived incomprehensibility of the instrumental suites on the second side, yet the general public had no problem with it - in the UK, the album rose to No. 2 (three positions higher than Station To Station), while in the US sales did drop down (No. 11 compared to Station To Station's No. 3), but even No. 11, for such a self-consciously "trendy European" record, must be seen as a huge success for David in the States. Essentially, it was the same "Bowie magic touch" that he'd never lost since the Hunky Dory and Ziggy days, being the only pop star who could take those oddly sci-fi Kraftwerkian ideas and make the world go crazy for them; and although much of that had to do with the success of ʻSound And Visionʼ, inarguably one of the catchiest pop singles he ever produced, the rest of the album sounds so unlike that song that there must have been other points of attraction...

In any case, these days the legacy has solidified: other than ʻSound And Visionʼ, the average Joe on the street will probably not remember even a single song off the record (how often do they play them on classic rock radio anyway?), but its critical reputation is unassailable, and it is typically being judged as the first and best representative of The Berlin Trilogy, with "Heroes" seen as slightly more self-indulgent and less memorable (a mistake, in my opinion) and Lodger as slightly less experimental and more hit-oriented (which might be the truth), although people rarely draw any truly serious dividing lines between the three (and some also view Station To Station as belonging to the same unitary group, since it was Bowie's first seriously "Europeanized" record after the R&B/funk flirt of 1974-75). Curiously, no expanded CD reissue has been available so far (at most, we got a couple unreleased outtakes from the same sessions), but now that Bowie's entire discography is getting a complete rehaul, with luxurious boxsets pumped out at a steady pace, chances are that pretty soon we will have a chance to poke our noses way deeper in his Berlin adventures than we used to.

For the

defense

From the opening notes of the instrumental ʻSpeed Of Lifeʼ, it becomes quite clear that nothing has changed, and everything has changed. That steady beat and triumphant guitar riff - these things could have easily opened any song on Aladdin Sane, serving as the backdrop for a cheerful, uplifting epic with the audience gleefully singing along. But there are no vocals this time, and instead of the vocals, we have a mish-mash of synthesizers, some disguised as heavenly strings in the background, some floating past in the foreground like spaceships running around their business. The composition does not experiment with time signatures, or toy around with dissonance - but the way it incorporates electronics is hardly suggestive of Emerson, Lake & Palmer, either: this ʻSpeed Of Lifeʼ sounds fascinating, like the speed of life in the (near?) future rather than the speed of life in 1977. It does not truly dispense with Bowie's glam roots, but it puts a futuristic crown on them, and even though it starts running out of ideas past the first minute, its mission is fulfilled very quickly. Yes, we can merge the unmergeable and fuse classic rock values with avantgarde sonic textures. And you know what, it doesn't even take that much time and strength to do it, as long as you understand which connections click and which ones don't.

But wait, it gets even more interesting. Behind all the talk about innovation, we often tend to forget that the album was recorded at an uneasy time for Bowie: a deteriorating marriage, a cocaine habit that had to be overcome, a public image scandal (the "Nazi salute" thing, probably a logical consequence of the coke habit but a separate problem anyway), and all of that, somehow, had to be reflected in the record - it wasn't called Low because Bowie was living in a basement or anything, you know. Several of the songs on the first side show us a deeply troubled Bowie - ʻBreaking Glassʼ gives us an angry, near-psychotic Bowie; ʻAlways Crashing In The Same Carʼ brings us a deeply depressive Bowie; and ʻBe My Wifeʼ is like a cross between the two - hysteria and depression all in one. The question is, how efficiently does the man make use of these new sounds to convey his turbulent state of mind? On ʻBreaking Glassʼ, one of the album's harshest rockers, all it takes is a three-note synth pattern that symbolizes his recourse to physical action ("baby... I've been... breaking glass in your room again... listen!" - WHEE WAA WOO); on ʻCrashing In The Same Carʼ, it's all about Eno's guitar treatments, giving the poor six-stringed beasts a sickly, poisoned timbre that are suggestive of the protagonist's own sickliness; on ʻBe My Wifeʼ, there's a virtual choir of synths and guitars rising in despair and anguish around the singer, weirdly combined with an overriding electric piano sound - it's like a New Wave take on ʻAll Along The Watchtowerʼ, but one where the guitar can never properly unwind itself into a traditional solo because... well, because now we do things differently.

In other words, it is fascinating to observe how Bowie's personal emotions, his classic rock background, and all the new sonic textures come together on these songs. But in the middle of all these grim pictures, we come across ʻSound And Visionʼ, and here the man is willing to show us that the same palette can be used for positive emotions as well: the song combines elements of dance-pop and R&B in order to emphasize its praise to "the gift of sound and vision", and, to capture the listener's attention, uses tricks that would very soon be utilized in an even more straightforward manner on Blondie's ʻHeart Of Glassʼ - a little ooh-aah, a bit of simple catchy harmonizing, a soothing synth canvas, and an irresistible dance beat. (Of course, the song is not completely happy - lyrics like "blue, blue, electric blue, that's the colour of my room" and "drifting into my solitude" still suggest the same loneliness as the other songs - but that's what is known as "advanced level perception", to be whipped out in the face of those who are only too happy to criticize David Bowie for selling out to all the shiny happy people). If not for the synth rain over your head, the song might have easily seemed like an outtake from Young Americans, but it is all about the synth rain, as well as about the odd hissing percussion which is simply there for extra weirdness' sake.

Of course, Bowie's most daring decision - a gamble, in fact, that properly paid off in retrospect rather than at the time of release - was to devote the entire second side to a lengthy instrumental suite, one that owed far more to Eno, Ash Ra Tempel, and Klaus Schulze than any of the classic symph-prog bands (who, by early 1977, were already well out of favor with the public). Ambient and minimalist, though with enough subtly dynamic melodic elements to not scare off most of the fans, its four parts do a good job conveying the atmosphere of desolation, loneliness, and hopelessness covering both Eastern Europe and the West Berliners, stuck in their city in a claustrophobic nightmare. Conceptually, the second side agrees with the first one - there's a subtle analogy between the artist, wallowing in his troubles and loneliness, and an entire city / country / region, existing in a similar state, what with the two halves of Berlin being forcefully divorced from one another (ʻBe My Wifeʼ, eh?). And while I can imagine just how many people listened to this and went, "That's not Bowie! That's all Eno! I didn't pay for Eno, you know!", all the tracks are credited to Bowie (except for ʻWarszawaʼ, where Eno did write the main melodic theme), hard as it is to recognize his writing style.

This is, actually, one principal thing that separates Bowie's work, no matter how experimental, from the experimental work of other people: Bowie rarely, if ever, engages in "experimentalism for experimentalism's sake". He always knows what he wants and he tries to get exactly that: and the ambient suite on Low is written with a quite explicit desire to generate a shivery atmosphere of ghostly desolation, hence all the heavy bass chords, the gloomy wordless vocals, the cold synthesizer tones, the pseudo-random flashes of jarring industrial noises. Absolutely the last thing to emerge out of the gloom and attract your attention is Bowie's own sax solo on ʻSubterraneansʼ, a bit Coltranian in style, if I might say so, but here, playing the part of the lone human spirit crying out of the wilderness and passing for either a last goodbye or a faint ray of hope, depending on which of the two you'd like to associate with Bowie (I vote for "ray of hope", since Bowie was never known to deprive his adoring audiences of one at the end of the day). If, at that point, you send out a memory probe to the very beginning, you realize that the album began by shaking you up, and then gradually proceeded to bring you down - lower and lower - in a most disturbing manner, and that all the short, energetic tracks on Side A now seem sort of fussy and vain compared to the solemn solitude of the suite. It's as if the deadly still figure of The Man Who Came Down To Earth on the album sleeve has melted away, and all that remains are the flames...

For the prosecution

And yet, after years and years of listening, I am still not sure that Low is truly as magical an experience as it is advertised. Even today, I cannot help thinking of it as, in a way, a grand rehearsal before Bowie's true Berlin masterpice, "Heroes". On Low, the man was already bold enough to wade into the treacherous waters of New Generation Music, using Eno as a safeguard, but had not yet developed the fully proper technique to swim across them. As good as the songs on Side A are, they are also, on the whole, either too short ("snippets" rather than fully developed songs), or too quiet, or too timid, to be able to compete with sonic beasts like ʻBeauty And The Beastʼ or ʻJoe The Lionʼ; and as catchy as ʻSound And Visionʼ is, it does not even try to match the epic wall of ʻHeroesʼ. And although the Low suite is almost universally acknowledged to be superior to its "rehashing" on the second side of "Heroes", I remain the lone dissenter who thinks that ʻSense Of Doubtʼ alone, in its windy minimalism, reaches far more terrifying heights than any part of Low, no matter how more densely arranged it is.

Low remains a pioneering effort, and an admirable one at that, but for all of its bold advances, it also seems strangely bent on keeping a "low profile". Notice, for instance, how Bowie's voice almost never rises above mid-volume level, as if he were consciously "deconstructing himself" from the record - on "Heroes", things would already be completely different, and although some might prefer this odd humbleness (especially if one is often annoyed by Bowie's narcissism that crops up, one way or another, on almost every other of his albums), I do not think that it really ties in all that well with the abrazive character of the accompanying music (on Side A, of course). The downside is that, like it or not, I still cannot remember tracks like ʻWhat In The Worldʼ or ʻA New Career In A New Townʼ at all, no matter how much I listen to them - ridiculous, I know, but I still believe that some of these tunes work better on a purely symbolic / intellectual level than an emotional one. In short, I wouldn't be surprised to learn that Low does reflect some traces of Bowie's physical and emotional exhaustion, and that would agree perfectly with my intuitive vision of "Heroes"-era Bowie as a reinvigorated artist in top form, and of Low-era Bowie as an artist who really wants to do good (major good), but kinda sorta needs a good night's sleep before doing it. Come to think of it, given what they write about his condition by late 1976, it's nothing short of a miracle that Low came out as good as it did.

Conclusion

| Melody | Voice | Mood | Production | Innovation/Influence | Where it belongs | RYM preference | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

#37 (Sep 11, 2016) |

| Previous entry | Main page | Next entry |