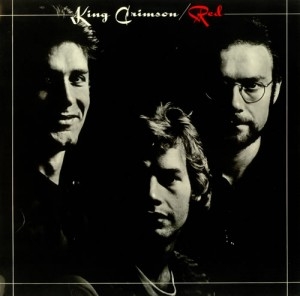

King Crimson

King Crimson

| Release date | Label | Producer | Genre | Length | More info |

| 1974.10.06 | Island/Atlantic | King Crimson | Prog Rock | 39:54 |

|

The perfect record for the late night intellectual coffee junkie.

Background

By mid-1974, it looked like progressive rock was in heavy trouble. Public interest in the genre, fueled by its freshness, boldness, and youthful arrogance, had peaked around 1971-72, when ELP, Yes, and Jethro Tull came across as highly marketable entities; but as the world got accustomed to the complexity and the genre-fusing trickery, boredom began to set in, and people started paying more attention to those rock critics who had always been skeptical of any attempts to make rock music into a "serious" (as in, "elitist serious") brand of art. The punk / New Wave revolution had not properly started yet, so there was not that much around to replace prog rock with, and, for the moment, Yes were still free to indulge in Tales From Topographic Oceans, and ELP could still put out their triple live albums, but public attention was already beginning to slip, the records were already selling less than they used to, and, worst of all, the "progressivists", as if encouraged by the public trust awarded them over the last few years, only made it worse by slipping deeper and deeper into their fantasy worlds, forgetting that there's only so much esotericity the people can handle before they send you to hell and start buying KISS albums instead.

Of all the "progressivists" at the time, though, nobody was smarter than Mr. Robert Fripp and his fellow Crimsonians (whoever they happened to be at the time). Having pretty much set the original prog-rock wheels in motion with In The Court Of The Crimson King back in 1969, King Crimson were also among the earliest bands to suffer from commercial failure (1970's Lizard was perceived as so completely inscrutable that the band fell out of commercial favor forever), and after the band's fourth album, Islands, ended up disappointing almost everybody, Robert Fripp underwent (or completed) the transformation that turned him into the immutable icon that is still with us today. From then on, he would (a) rarely, if ever, care about sales and "acceptance"; (b) but seriously care about always staying up with the times, steering his music into the most promising and cutting-edge artistic directions and never looking back to the past. And already in 1973, to Fripp, "symphonic progressive music" of the Yes/ELP variety (and of his own ITCOTCK variety, it would seem) was a thing of the past - even before it soured so definitively as to become critical poison and commercial suicide. The new thing, according to Fripp, was radically uncommercial (the new look KC would not dirty their hands by going into the glam-rock business!), but critically viable - a mix of the heavy rock idiom with avantgarde, free-form jazz, and proto-ambient sonic experimentation of the Krautrock / Brian Eno variety. Something even more complex and classy than Can, in other words, because for all their relentless innovation, Can could be seen as stuck way too much in the traditional blues-rock idiom; Robert Fripp would never allow himself something as "banal" as that.

The first two albums released in King Crimson's new style, Larks' Tongues In Aspic and Starless And Bible Black, were artistically successful (although Starless did veer too much in the direction of not-fully-inspired live improvisation), but it was not really until Red that the new look band found a perfect balance between form and content - in other words, convinced the demanding listener that this new style was not there simply because it was new, but because it was actually a new way to say some important things. Ironically, just as the record was in its final stages of preparation, Fripp hit rock bottom with a personal crisis, accepted Gurjieff as a (temporary) spiritual guru, and finally split the band with no intention of ever reassembling it again. Much of that personal crisis can already be felt on the songs themselves, and in a way, Red does bring the story of the original King Crimson full circle, ending with pretty much the same disturbing atmosphere with which the band had first started out on ʻ21st Century Schizoid Manʼ. So what is it, exactly, that makes Red arguably the most important and conclusive musical statement of 1974? Read on to find out.

Some basic factsUpon release, the record charted fairly low, and Fripp's announcement in late September of 1974 that King Crimson was officially dead hardly made any waves. Since most of the album was written and recorded after the band's last tour was concluded, only ʻProvidenceʼ and ʻStarlessʼ had had enough time to be well-refined onstage. Also, since Fripp was smitten with his personal crisis already before the album went into pre-production, the final product may seem a bit too strongly tilted into the direction of John Wetton's soulfulness - which probably explains why, once King Crimson was again resurrected in the early 1980s with Fripp at the steering wheel, the only track to survive in the setlist was ʻRedʼ itself, the album's only pre-composed instrumental. But despite all these problems, the reputation of the album has only continued to grow, and even in the darkest period for progressive rock as a whole, with the "Rolling Stone mentality" ruling the critical waves, even the most sardonic enemies of the genre left a soft spot for Red as "the album that really said it as it is", almost sort of a rebellious statement that went against the grain at the time - a somewhat distorted understanding, at the core of which, however, does lie the inarguable fact that the prog-rock of Red was vastly different from almost everybody else at the time.

As with most of King Crimson's catalog, Red was treated to a whole series of remasterings and re-releases, the latest of which featured a complete remix (first in 5.1, then in proper stereo) by Steven Wilson of Porcupine Tree (I have the 2013 edition with the original and the re-mix, but still haven't gotten around to properly comparing the two - not that I'm that much of an audiophile, but Wetton's vocals do sound somewhat cavernous on the original). And, of course, for true loyalists there's always The Road To Red - a mammoth 24-CD set that contains soundboard recordings of pretty much every single show (or, at least, the vast majority of them) that the band played on their final tour, even if, as it has already been said, the only composition from Red to have been played on that tour was ʻStarlessʼ. Of course, you cannot call yourself a true fan unless you've memorized every single disc of that one (or owned the complete King Crimson catalog on CD, for that matter, which can only be done if you throw out your partner to make enough space for all the discs).

For the

defense

The simplest thing in the world would be to call Red a "dark, brooding, apocalyptic vision of an album" and end it right there. Nobody could really seriously deny this anyway, and people who truly love music usually love dark-brooding-apocalyptic, so that's that. The problem is, Red is also a King Crimson album, and ever since it became obvious that Robert Fripp was King Crimson, and everybody else was just serving a certain amount of time in His Majesty's Government, it also became obvious that no King Crimson album would ever comfortably fit a simple, one-line definition. For one thing, Fripp hardly comes across as an overtly gloomy, fatalistic kind of guy: even when everything really begins to fall apart and the Four Horsemen appear on the horizon, he will probably still be sitting on his little stool, immaculately dressed and immersed in composing a last-minute soundtrack to events in a parallel universe. For another thing, ever since the original King Crimson dissipated and the band freed itself from the operatic nature of Greg Lake's voice and the cosmic depths of Ian McDonald's Mellotron, KC music was rarely, if ever, about the grand open spaces and large-scale cataclysms - on the contrary, it was deeply introverted, with a sort of "anti-arena rock" vibe where the music could kick as much ass as any stadium anthem, but stay all the time "within you" rather than "without you". To that end, Red burns hot and bright, but with a strange, inner flame, where you have to enter the furnace and politely close, lock, and bolt the door behind you before you get the right to properly feel the burn.

Take the title track, for instance, probably the heaviest rocker of King Crimson's entire early and mid-period (and one that still proudly stood its ground even after 1994, when the band began getting real heavy once again). From the very first seconds, its heaviness is undermined by the odd, thin, whiney tone of the lead guitar, playing the opening riff three times in a row, each time higher and higher until the pitch gets dangerously close to ultrasound level. This is not a glam-rock / arena-rock kind of thing, nor is it a Black Sabbath kind of crunch, nor is this a merger of psychedelia and hard rock in a Hawkwind way - this is the soundtrack to your local mental strain, the sound of your brain as it encounters a threatening, potentially lethal challenge and begins to run in circles, trying, now in a collected and logical manner, now in a total panic, to circumvent it. Red is sometimes named among the progenitors of "math rock", and ʻRedʼ is, indeed, the perfect early math-rock composition, where the main riff sounds like somebody trapped in a labyrinth, making one attempt after another to get out of it, to break some invisible barrier with a set of well-calculated moves. Around 2:50 into the song, comes a temporary breakdown, as logic gets replaced by panic, but the panic attack is brief, and eventually, we get back to the algorithm, and when the opening theme returns in the form of a coda, it's like a light at the end of a tunnel. Too bad the video era was not yet upon us: ʻRedʼ just screams for an accompanying animation of a suspenseful journey through dark tunnels and treacherous warp holes. It's not just psychedelic chaos like the one generated by early Pink Floyd or classic Amon Düül II - it's a brave stab at a rational representation of the darkest subconscious. An amazing combination of instinctive dread-'n'-doom with meticulous planning and logical analysis, and one that you just do not find these days even with the best "math-rock" ensembles.

The two vocal tracks that follow are almost obligatorily weaker, mainly because they have vocals - and I am not sure if they mixed Wetton's voice so strangely purely by accident, or because Fripp expressly desired to keep the powerful vocalist in the aisles rather than upfront, so that there'd be no danger of turning the record into another operatic showcase. Not only that, but the lyrics to ʻFallen Angelʼ would have probably fit in much better on a Thin Lizzy album, with a morbid tale of two brothers not faring well in New York City's gangland that could have hardly been farther removed from whatever was going through Robert's mind at the time - but that is merely to reinforce the idea that the last thing that matters on a King Crimson album are the words, particularly after they'd parted ways with Peter Sinfield. What really matters here is the contrast between the main balladeering theme, almost peacefully pastoral with its oboe and cornet overdubs, and the jazzy chorus / bridge sections, where Fripp's nagging guitar part, like an alarm signal gone wrong, is intertwined with free-form jazz brass soloing, which I probably could not have tolerated if it were on a jazz record, but together with that guitar part, the effect is strangely oppressive and haunting. You will hardly remember this tune as a passionate social statement, but if you give it a good chance, you will always remember it as a mesmerizing duel between moments of inner peace and psychic turbulence (not to mention the last time ever you will hear Robert Fripp play a bit of acoustic guitar).

The lyrics are a tad better on ʻOne More Red Nightmareʼ, which is, contrary to desirable associations, not about John Wetton preventing a communist plot to kidnap Robert Fripp and appoint him head of the Moscow Symphony Orchestra, but rather about the protagonist's fear of flying - again, the word "red" implies a subconscious flashing alarm signal, and the track does feature the most psychotic verse melody on the entire album, although most of it is given over to a slower, subtler section that merges... heck if I really know what it merges: folk-rock guitar patterns, crazyass time signatures, and a sax part from Ian McDonald that is more R&B than jazz in nature. However, the opening riff again returns us to the math-rock territory of ʻRedʼ, like a conundrum waiting to be solved, and so, once more, we get the impression of an entrapped spirit trying to break free - caught in a "red nightmare" that is so endless, the only way to get rid of it is to abruptly cut the track around 7:09, the same way the Beatles did with ʻI Want You (She's So Heavy)ʼ five years back.

The second side of the album consists of but two tracks, heavy on jam power, and while many people (myself included) tend to regard the live improv ʻProvidenceʼ as a piece of filler that lacks focus and a sense of purpose compared to the other tracks, I cannot help admitting that, atmosphere-wise, it fits in perfectly with the rest - same psychodarkness all over the place, with Fripp's high-pitched guitar tones, Wetton's thick metallic bass grumbles, Bruford's poly-frickin'-rhythms, and David Cross's excruciating violin warbles. All that is really needed is some sort of memorable theme to complete the package - but once you get to the juicy part when the "Power Trio" begins unwrapping its potential in earnest (rather than just chilling and waiting for Cross to finish torturing his violin), even that is forgotten. However, on the whole, the "one more red nightmare" of ʻProvidenceʼ is really just a big introduction to the album's magnum opus - ʻStarlessʼ, formerly ʻStarless And Bible Blackʼ before Fripp, out of his usual contrariness, decided to give that title to another composition and put it on another composition.

It is fairly clear why Fripp disliked the song originally - Wetton's vocal delivery again borders on operatic, and the lyrical message of depression and desperation is not far removed from whatever territory the band had already covered with ʻEpitaphʼ, a stage that Fripp thought was already completed. But in the end, he did like it enough to throw on an almost nostalgic Mellotron part, and invent a guitar part for the main melody that sounds like the weeping song of an alien... or, rather, of the little green man deep inside your brain, who only gets activated late at night ("starless and bible black", see). And he compensated for everything with the last seven minutes of the tune - of course, that slow, diligently conducted crescendo is one of the most stunning moments in King Crimson history, with the gradually ascending guitar leading the rhythm section on and on, higher and higher, until you just can't take it any longer. I have a hard time trying to come up with a better example of psychic tension, where the spirit inevitably winds itself to breaking point, anywhere in rock music.

In the end, it's not about the end of the world, and it's not even about insanity (another favorite subject in art rock), but it is about the hidden manoeuvres of the subconscious, and how there's order in its chaos and chaos in its order - something like that (even though I am still searching for a way to state that better) has always been my impression of Red, and, for that matter, the majority of King Crimson's material both in the 1973-74 and in the later (though not earlier) periods. If it doesn't make much sense to you, it doesn't exactly surprise me, because records like these are unique - they don't really let you apply the usual cliches about depression, desolation, darkness, and destitution.

For the prosecution

I am not sure if there is even one completely perfect progressive rock album out there (in my understanding), but it's pretty much like it is with Wagner operas - you have to attune yourself to the background in order to savor the great moments as they come at you, one by one, in slow, but steady succession. Not every second of Red should leave you with your jaw open, and pretty much every single track here, I think, is at least a tad overstretched: I would see no harm in trimming some fat off the sax jams in ʻOne More Red Nightmareʼ, in limiting Cross' time with the violin on ʻProvidenceʼ, and maybe even in cutting off a minute or so off the title track (the main riff is so instantaneously catchy anyway that replaying it over and over adds little to the initially accumulated awesomeness). However, this would only make sense in order to accommodate at least one or two other tracks of equal caliber, provided they had them - and if they didn't, there's no harm in a little bit of padding. I do have to say, though, that I'm a little disappointed in ʻStarlessʼ after the crescendo - that passage is so intense that the only thing it could have successfully resolved itself into would be a mega-monstruous jam at the top of the trio's insane powers, something worthy of a ʻ21st Century Schizoid Manʼ at least, and, well, there's a little bit of that, but not enough for my taste - we really needed a shattering, staggering coda, and instead of that, the whole album just kind of fizzles out at the end. Maybe it's symbolic or something, but I don't quite like that.

The other point of contention has been mentioned already: John Wetton as a songwriter and singer - probably the weakest link in the trio (although far be it from me to question his abilities and decisions as a bass player). In some ways, you can already sense the future frontman of Asia, get the feeling that he is simply aching to get more of his soulfulness and sentiment on the record, except that slave driver Fripp is not letting him go all the way. Still, at worst, I never have any real problems with the way he's handled on these songs, and at best, he kicks up a good ruckus (I think ʻOne More Red Nightmareʼ is his crowning moment of glory here), and the vocals are only a very minor part of the experience anyway - most of the time, it only matters how well he is coordinated with the other members of the band, and I guess Fripp wouldn't keep him in the band if he weren't well coordinated in the first place...

Conclusion

| Melody | Voice | Mood | Production | Innovation/Influence | Where it belongs | RYM preference | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

#38 (Sep 18, 2016) |

| Previous entry | Main page | Next entry |